2005 09

The 34th Conference of Economists in Melbourne was one of the better ones held in recent years. It was great to meet some IE readers for the first time, as well as catching up with some old friends. RBA Governor Macfarlane gave another great speech on global imbalances at one of the satellite business symposia, which neatly debunks much of the popular commentary on this subject:

My view is only that we should not start our analysis with the US current account, or look to its remediation as the key to unwinding the imbalances. For example, the most commonly heard prescription is for the United States to reduce its call on world savings by reducing its fiscal deficit. However, if my analysis is correct, a reduction in the US fiscal deficit by itself would be unlikely to have a major impact on international imbalances. In the absence of policy changes in Asia, the Asian countries would be likely to continue running surpluses, and so a fiscal contraction in the United States would only add a contractionary influence to a global economy already characterised by surplus saving and unusually low interest rates.

Another view that has recently been put is that it was excessively loose monetary policy rather than saving/investment imbalances that was at the heart of the problem. This view is generally bolstered by some reference to excessive liquidity, although the concept is left undefined. I do not find this argument at all convincing. There is no doubt that world interest rates have been exceptionally low, but does that of itself mean that monetary policy has been exceptionally loose? To maintain this view, you would have to believe, for example, that monetary policy in Japan and Europe , where there has been weak demand growth and negligible inflation for a number of years, should have been tightened, i.e. European and Japanese interest rates should have been raised. This would make no sense. The low level of interest rates in most developed countries is not the first cause of the global imbalances, it is the result of them.

posted on 28 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Laissez-Faire Books has a 15% off everything sale through to 15 October. LFB claim to be 30% cheaper on average than Amazon and offer to match Amazon prices on available titles.

posted on 24 September 2005 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

I will be attending next week’s Conference of Economists in Melbourne and giving a paper on Japanese Monetary Policy under Quantitative Easing: Neo-Wicksellian versus Monetarist Interpretations (the full list of conference papers can be found here). My paper is scheduled for the Monetary Policy session kicking-off at 11:15am Monday in the Old Arts Theatre.

Looking forward to catching-up with IE readers at the conference.

posted on 22 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Max Corden calls for the de-Stalinisation of higher education in his Sir Leslie Melville Lecture. I seem to recall one ANU economist back in the 1980s presciently referring to the Dawkins White Paper as a GOSPLAN for higher education.

posted on 21 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Johan Norberg, author of In Defence of Global Capitalism, will be giving a free lunch time forum at the Australian Graduate School of Management, University of New South Wales, on Wednesday 12 October between 1:00-1:45 pm. The topic for the forum is Why Globalisation is the Cure for Terrorism. RSVP by 10 October: rsvp at agsm.edu.au.

Norberg is profiled here.

posted on 20 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Forget John Bolton. Tim Blair has found the man to clean-up the UN.

posted on 19 September 2005 by skirchner in Foreign Affairs & Defence

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

An op-ed in the WSJ previews a forthcoming article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives that distinguishes between house prices and the cost of owning:

We, along with Charles Himmelberg, a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, computed annual housing costs for 46 housing markets from 1980 to 2004 in a study due to be published this fall in the Journal of Economic Perspectives. Our findings are striking. In none of the hottest housing markets did the ratio of the cost of owning to rent in 2004 exceed the average over the sample period in their own market by more than 13%. The highest was in Portland, Ore. Miami’s ratio was 12% above average. But the ratios in the other oft-cited “bubble” cities such as Boston, L.A., New York and San Francisco were no more than 3% above their long-run averages…

The number one reason the current cost of owning differs so much from the price of a house is the historically low level of real, long-term interest rates. Low rates reduce the yearly cost of financing and lessen the cost of tying up capital in the house. At a lower cost-per-dollar of housing, families are willing to spend more for a house, bidding up prices.

UPDATE: Full paper here.

posted on 19 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The FT has a very amusing round-up of failed predictions in relation to UK house prices, demonstrating once again the perverse demand for predictions of housing-related economic ruin. The author really nails it when he notes the inability of the commentariat to get their head around the concept of capitalist acts between consenting adults:

And yet house prices continued to defy the reasoning of such commentators. Unlike many other assets, such as gilts or equities - which usually are influenced mainly by professional decisions - housing is an incredibly democratic market. The average price of a home is entirely a function of decisions, sensible or otherwise, by millions of ordinary people buying or selling homes. Should they decide that it is rational to borrow six times their salaries, when renting might be much cheaper, there is little the intelligentsia can do about it.

The author also quotes this very sound advice from the Bank of England’s Mervyn King, which the RBA would do well to heed:

The best way to destroy the credibility of the monetary policy committee is to lecture people about house prices.

posted on 17 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(11) Comments | Permalink | Main

$49.95 according to the NYT. I’m all in favour of mainstream media charging for content. We need more price signals in the market for opinion. In Krugman’s case, I suspect even his fans would hesitate at giving up a modest amount of green to read a product that has become so absurdly predictable.

posted on 16 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Is current account and budget deficit angst just a bad Oliver Stone movie cliché? BlogginWallStreet quotes Gordon Gekko in Wall Street:

Well ladies and gentlemen, we’re not here to indulge in fantasies, but in political and economic reality. America has become a second rate power. Our trade deficit and fiscal deficit are at nightmare proportions.

If it was a movie cliché in 1987, it must surely be getting pretty long in the tooth in 2005. Plus ca change…

posted on 15 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

The world’s first economics blog turns ten this month. I’m talking about Morgan Stanley’s Global Economics Forum. The GEF obviously predates blogging as we now understand it, but in retrospect it is clear that blogging is what they have been doing all these years. The GEF is most notable for carrying the work of Robert Feldman, perhaps the best Japan economist in the business.

It is unfortunate that Morgan Stanley chief economist Stephen Roach and Andy Xie have become so preoccupied with ‘bubbles’ in recent years. Andy Xie is increasingly sounding like a hard-money Austrian, with everything reduced to an excess liquidity story that is indistinguishable from the pop Austrian simplification that the business cycle can be reduced to fiat money supply errors. I once thought that ‘bubbles’ were a temporary fallback position for those whose analytical frameworks had failed them, but it is now obvious that, for many analysts, ‘bubbles’ are an all-purpose explanation for everything, devoid of any analytical content.

posted on 14 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The IMF has released its Article IV consultation with Australia. IMF staff modelling confirms something that we have been arguing for some time:

Controlling for other variables, household equity withdrawals were found to have negligible effects on consumption. Disposable income, real interest rates, and net housing wealth are the key determinants of household consumption expenditure in Australia, with changes in net financial wealth having little effect. Overall, it appears that housing equity withdrawals are not a driving force for consumption in Australia, rather they are more a source of financing.

As the IMF notes, the RBA is to release the results of its research on this issue later this year. Early indications are that this research will be a severe embarrassment to much of the conventional wisdom about the role of housing-related credit in the Australian economy.

Meanwhile, the World Bank ranks Australia sixth for ease of doing business. New Zealand is number one, which might explain why it has the lowest unemployment rate in the OECD (thanks to New Economist for the pointer).

posted on 13 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Not according to Action Economics chief economist Mike Englund:

The average spread in the second half of expansions is only 17 basis points. And, not only is the average low, but note that the yield curve is notable flat largely throughout the second half of every expansion. The pattern reflects a strong cyclical tendency for the Fed to bring the Fed funds rate roughly in line with Treasury yields in the second half of each growth period, and not to some point well short of the 10-year yield. As we and others frequently note, yield curve inversions are a powerful predictor of business cycle downturns, but even then the usual lead time is a hefty 9-20 months. This means that an inversion today would only signal a recession before May of 2007…

Now, with little more than a narrowing of the spread toward the usual “second half” gap, we can only guess that the expansion is approaching the mid-point.

posted on 13 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Guess who wrote the following?

Only John Howard could deliver the socialist dream: a welfare state that supplies more than 14 per cent of household disposable income, up from 9 per cent at the end of the Hawke government and 6 per cent in the Whitlam era.

Since the Howard Government came to office in 1996, real disposable incomes have risen by about 15 per cent and unemployment has fallen to its lowest level in 30 years. That’s good. But it also means welfare dependency has fallen sharply.

So why has the Howard Government increased real social security spending by almost half? The answer has nothing to do with national welfare dependency and everything to do with politics. Howard’s welfare state has been highly effective in taxing single people and couples without children and giving the proceeds to couples with children…

The latest Treasury Economic Round-up backs the findings reported in The Australian. It reveals that almost 40 per cent of families receive more in welfare than they pay in tax…

But the welfare state is out of control. The wealthy do not need government cash handouts and low and middle-income earners don’t need the punishing tax rates used to finance them.

Labor MP Craig Emerson. We look forward to hearing what the Australian Labor Party intends to do about it.

posted on 13 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Gittins effectively exposes his own caricature of those who argue for reductions in the highest marginal tax rates in today’s column. Reducing high marginal rates has never been primarily about inducing increased labour supply from high income earners. Indeed, Gittins is the only person who takes this straw man at all seriously. Lowering the top marginal tax rate has always been about removing costly distortions, a case he acknowledges in today’s column, albeit with the thinking done for him by ANZ chief economist Saul Eslake.

Regular readers will note that I have important differences with other reform advocates on this issue. In particular, I question the emphasis on removing concessions as the best way to lower rates, since this just leaves us with the same tax burden spread over a broader base. I would prefer the emphasis to be on funding lower rates through net reductions in government spending. But the general principle of seeking to align rates at lower levels is a sound one.

A closely related reason for lowering high marginal rates is eliminating the enormous waste of resources in tax planning, compliance and collection. Very few high income earners pay the top marginal rate, but only after they have devoted considerable resources to avoiding it. These resources all have opportunity costs attached. What struck me most about being a taxpayer in Singapore was not the low rates (welcome though they were), but how little it cost me to comply with the law: a few minutes of my time and a postage stamp each year, with no need for an accountant, much less a lawyer.

posted on 12 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ross Gittins is again in wowser mode, talking down the Q2 national accounts and the growth outlook. Like many economists, he takes the view that because consumption accounts for 60% of GDP:

where consumption goes, the economy follows.

If anything, the relationship is the other way around. The standard approach to modelling consumption is to include national income as an explanatory variable, implying causality runs from income to consumption. What people consume out of is in fact expected income. To say that consumption accounts for 60% of GDP is just an artefact of classifying GDP on an expenditure basis. We could equally define it on an income or production basis, with no reference to consumption at all.

The view that consumption drives the economy leads many analysts astray, not least in grossly exaggerating the wealth effects from changes in house prices. As we have argued previously, the fact that consumption and national saving have remained remarkably steady as shares of GDP in recent years makes a nonsense of claims that the Australian economy depends on house price driven consumption spending.

posted on 10 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Do Malcolm Turnbull’s tax reform proposals really have their origins in brawls with the anarchist left of the 1970s?

The future treasurer confesses all to Turnbull about being bashed up by anarchist Red Bingham, a bruising encounter that resulted in a $150 fine and a photo press call for newspapers.

Bingham also dishes the dirt to Turnbull, admitting that “by beating up Costello, I wanted to expose the entire bourgeois morality on which his existence rested”.

“I wanted to expose his faith in the bourgeois law courts, the bourgeois traitor press and the resurgent fascists in Canberra,” he explains.

Was Red the inspiration of Turnbull’s recent 51-page assault on the Treasurer’s tax reform credentials that will now be assessed by Treasury officials?

The millionaire MP isn’t saying.

posted on 10 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The August labour force figures, like the Q2 national accounts, were underreported today, although I did like this headline:

‘Jobs boom defies doomsayers’

No, I’m not moonlighting as a sub at the AFR. A new record in the labour force participation rate, together with the maintenance of 30 year lows in the unemployment rate, is now apparently considered almost routine and not particularly newsworthy.

In policymaking circles, there have been some fairly heated exchanges about what is going on with the data, with the RBA in particular questioning why the strength in the labour force data does not square with some of the activity data. This issue was partly resolved when the ABS found an error in its compilation of the retail trade data, but there is still an issue over the relationship between GDP and employment.

The ABS addresses this issue in an article accompanying the Q2 national accounts release. The ABS argues that the apparent lag between the slowdown in GDP growth and employment growth is not unusually long. The implication is that we should expect some weakness in the employment data ahead. There has also been some weakening in ANZ job ads, which is a good leading indicator of the labour market.

Abstracting from the cyclical influences on the labour market, Australia has broken out of the old trend in which peaks and troughs in the unemployment rate were successively higher to a situation in which they now appear to be moving successively lower. It is still a sorry performance compared to New Zealand’s 3.7% unemployment rate and record 67.7% participation rate, but no less welcome for that.

posted on 09 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

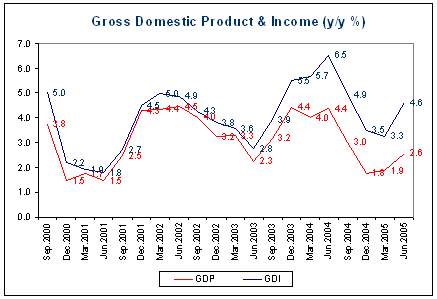

Proving once again that there is no market for good news, yesterday’s Q2 national accounts release attracted relatively little attention compared to the hysteria that accompanied the Q4 release. The most remarkable feature of the Q2 release was the large wedge that the stunning double-digit growth in Australia’s terms of trade has driven between the gross domestic product and income accounts (shown below in y/y terms).

Gross domestic income rose 2.4% q/q compared to the 1.3% q/q rise in GDP. GDI better captures the welfare gains arising from the increased purchasing power of domestic production that flows from an improved terms of trade. It also puts the current account deficit in perspective, by showing the enormous welfare gains from substituting low cost imports for domestic production.

Needless to say, the economic Armageddon that was supposed to be unleashed by falling house prices is nowhere in sight. No doubt weakness in house prices has further to run and will have a small negative wealth effect. But the dwelling investment cycle appears to have turned already, with both dwelling investment and ownership transfer costs making positive growth contributions in Q2.

posted on 08 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

I don’t mind the WSJ running a puff piece on Australia and Prime Minister John Howard, but at least get the facts straight:

When he entered office in 1996, unemployment was 9%, interest rates hovered around 20%.

No, the unemployment rate was 7.6% and the official cash rate was 7.5%.

Then there is this:

the debt is a puny 4 billion Aussie dollars.

True enough, but why stop with the current net debt figures. In 2008-09, general government net debt is projected at -$56,389 million or -5.3% of GDP. But I’m guessing that a negative net debt position would be a little too tricky for the WSJ to explain to its readers.

posted on 05 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

Alan Reynolds on speculating against the Strategic Petroleum Reserve:

Energy Secretary Bodman announced he had “approved a request for a loan of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve” and “continues to review other requests as they come in.’’

That announcement should have been made by the president at least a week before the hurricane actually hit. He should have said, “The United States stands ready to replace all oil production loss resulting from the hurricane for as long as necessary.” If that had happened, oil would now be at least $10 a barrel cheaper than it is. Since 1991, however, it has always been safe for traders to bet against the SPR being used in such a serious way.

posted on 05 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Natural disasters always bring out plenty of instances of Bastiat’s broken window fallacy. However, to point out the implications of disasters like Hurricane Katrina for measured growth is not necessarily to fall victim to the broken window fallacy. It is simply to highlight the well known limitations of the ways in which we measure economic activity, particularly for flow based measures like GDP. This is not the same thing as claiming that we are better off in a welfare sense as a result of a natural disaster. No doubt some commentators are not clear about this distinction, but it is also clear that many of those who are pointing out the fallacy in the context of Katrina are not clear about the distinction either.

Understanding the distortions to measured activity arising from events like Katrina is an important task for economists. Action Economics Director of Investment Research and Analysis Rick MacDonald is an expert at sifting through the implications of hurricanes for US economic data. For those wanting a good handle on the implications of Katrina for these data, I would highly recommend his research.

posted on 04 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Paul Kelly has some hard questions for Peter Costello on Malcolm Turnbull and tax:

What else are backbenchers supposed to do? What conclusion about Costello will other backbenchers draw? And it is backbenchers who make and break leaders…

Is it hard in political and financial terms? Of course. But what, exactly, is Costello’s problem? Does he object to the design or the politics or just the impertinence?

posted on 03 September 2005 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Malcolm Turnbull exposes Treasurer Costello’s empty rhetoric on tax reform:

there is simply no financial or economic justification for maintaining the 47 per cent rate. Its only justification is political: “soak the rich”. But such a rationale is completely disingenuous. After all, anyone who is not a PAYE taxpayer can easily and legally structure their affairs so they don’t have to pay it.

posted on 02 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

As an undergraduate back in 1987, I was one of several contributors to a book published by John Hyde’s Australian Institute for Public Policy, Compulsory Students Unions: Australia’s Forgotten Closed Shop. Other contributors were Michael Danby, now a federal Labor member of the House of Representatives and Mark Trowell, now better known for his role in the Shapelle Corby case. The introduction was written by a young barrister by the name of Peter Costello. My chapter argued for the use of federal financial powers by a future Liberal government to coerce universities into adopting voluntary student unionism, on the grounds that the right of individuals not to be coerced into membership of student associations trumped the rights of state governments and university autonomy. The book and some of its authors were instrumental in having these policy prescriptions written into federal Liberal Party policy (and now, to a lesser extent, Labor Party policy), so I feel some responsibility for the policy the federal government is now following to make student unionism voluntary.

continue reading

posted on 01 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

If a job’s worth doing, get an Australian to do it. Terry McCrann makes the case for RBA Governor Macfarlane to become the next Fed Chair. Now we know why Macfarlane wanted his term extended only three years!

posted on 01 September 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

|