|

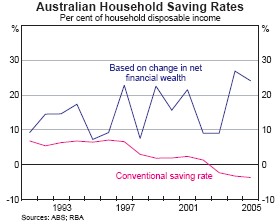

One of the more pernicious myths about the Australian and US economies is that their household sectors do not save and have lower saving rates than other industrialised countries. This largely reflects the much higher rates of household ownership of equities in Australia and the US than other countries, an important economic strength rather than weakness, but one that is not captured by conventional measures of household saving.

The RBA’s May Statement on Monetary Policy calculates a broader measure of household saving based on net financial wealth. As the RBA notes, this measure ‘presents a more realistic picture of Australian household saving behaviour than conventional measures.’ It shows a steady trend in household saving.

posted on 05 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(6) Comments | Permalink

Brendan O’Neill makes the case for bin Laden as blogger:

The latest statement reveals the extent to which bin Laden borrows from Western discussions of the Middle East. He seems less a man with a clear religious or political agenda than a parasite feeding off the fear and loathing of his enemies…

Bin Laden’s reliance on Western theorizing about the reasons for Al Qaeda’s existence and actions is clear in Messages to the World. Reading his statements from 1994 to 2004, one can see clearly that he transforms himself from a religious crank obsessed by Saudi Arabia (circa 1994) to a self-described warrior for Palestine (around 2001–02) to a full-fledged Bush basher (from 2004 onward). His campaign is shaped less by his own program of ideas or aims than it is by the West’s interpretation of that campaign.

O’Neill is wrong to suggest that the echo chamber quality of bin Laden’s statements is symptomatic of a lack of purpose. The fact that bin Laden is cynical and opportunistic enough to position himself within Western intra-mural debates shows that he studies his enemies’ internal divisions and seeks to exploit them…even to the point of having a position on Kyoto.

posted on 03 May 2006 by skirchner in Foreign Affairs & Defence

(2) Comments | Permalink

2004 Nobel Prize in Economic Science winner Ed Prescott will be giving a lecture at UNSW on 1 June, titled ‘Unmeasured Investment and the 1990s US Boom.’ Here is the abstract:

During the 1990s, market hours in the United States rose dramatically. The rise in hours occurred as gross domestic product (GDP) per hour was declining relative to its historical trend, an occurrence that makes this boom unique, at least for the postwar U.S. economy. We find that expensed plus sweat investment was large during this period and critical for understanding the movements in hours and productivity. Expensed investments are expenditures that increase future profits but, by national accounting rules, are treated as operating expenses rather than capital expenditures. Sweat investments are uncompensated hours in a business made with the expectation of realizing capital gains when the business goes public or is sold. Incorporating expensed and sweat equity into an otherwise standard business cycle model, we find that there was rapid technological progress during the 1990s, causing a boom in market hours and actual productivity.

Follow the link for some related papers.

posted on 03 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

BCA President Michael Chaney in the WSJ, proving that international comparisons are what you make of them:

We are particularly concerned that there is no overarching plan or vision for Australia’s tax system…

Mr. Costello’s review, which has confirmed that key areas of the Australia’s tax system are not competitive and need immediate reform, provides the conceptual groundwork for a program of more comprehensive and sustained reform.

Unfortunately, Treasurer Costello intends the review as a rationalisation for inaction.

posted on 02 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

With the big dollar rebounding after money honey Maria Bartiromo disclosed her conversation with Ben Bernanke, its time to review the Top 10 Reasons You Know You Watch Too Much CNBC.

posted on 02 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

An article in the most recent RBA Bulletin discusses the implications of a trend we have highlighted on this blog many times before: the growing stock of Australian investment abroad, particularly direct investment capital. Australia’s stock of foreign assets is growing faster than its stock of foreign liabilities. As the article notes:

Australia’s external assets are relatively skewed towards equities while liabilities are more skewed towards debt. As such, the valuation gains on assets in absolute terms on average exceed those on liabilities. One corollary of this is that the official measure of the current account deficit probably overstates the true ‘economic’ deficit, since the valuation gains are part of the overall return on foreign assets, but are not measured in the current account which includes only income flows…

In Australia’s case, if we were to treat the net valuation gains on foreign assets as all being part of the ‘income’ from these investments and include them in the current account, the current account deficit would have been on average about 0.3 percentage points of GDP per year lower than was actually recorded over the 15-year period.

The article also examines the implications of hedging for the change in Australia’s net foreign liabilities as a result of an exchange rate depreciation. The results make a nonsense of Nouriel Roubini’s recent forecast of a currency and financial crisis in the dollar bloc periphery.

posted on 01 May 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(7) Comments | Permalink

A Colombia GSB student, with a striking resemblance to Glenn Hubbard, sending-up Hubbard’s supposed tilt at the Fed Chairmanship, to the tune of ‘Every Breath You Take.’

(via John Mauldin)

And coming soon to a cinema near you, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie as John Galt and Dagny Taggart.

posted on 29 April 2006 by skirchner in Culture & Society

(0) Comments | Permalink

Never mind bloggers in pyjamas, here Brad DeLong discusses the ‘mystery’ of US capital account dynamics - in his dressing gown!

When you have recovered from seeing Brad in his bath robe, see Pamela Anderson as you have never seen her before…on the Wall Street Journal op-ed page.

posted on 28 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

The WSJ editorialises on the IMF’s on-going fight against its own redundancy in a world of floating exchange rates and international capital mobility:

These are grim times at the International Monetary Fund; the world economy is too good. Global GDP has expanded by nearly 5% over the past three years, capital and trade are reaching far corners of the earth, and millions of the world’s poor are being lifted out of poverty. So naturally the IMF is worried.

That’s the backdrop of the weekend agreement in which the world’s developed nations agreed to give the Fund the task of lobbying to correct “global imbalances.” The idea is that the world’s trade and capital flows are out of whack, and are thus a grave threat to all of this prosperity. What the world needs now, said IMF Managing Director Rodrigo Rato, is “coordinated action” to unwind these “imbalances.” And who better to lead it but the Fund, through “multilateral surveillance” of problem countries.

There are few things more dangerous than a global bureaucracy looking to fix something that isn’t broken. Trade and capital flows are a function of millions of private decisions, so it’s far from clear that “imbalances” need addressing. Yes, the U.S. is importing huge amounts of capital and traded goods. But this is in part because the U.S. economy is growing so well, while Europe’s big three—Germany, France and Italy—are dead in the water. If Mr. Rato wants to roll a boulder up a hill, how about lobbying those countries to shape up?

posted on 27 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

I have only recently returned from a few weeks in Europe. Thanks to all those who made it such an enjoyable trip. It was good to meet with some IE readers for the first time and to get some great first-hand insights into the UK and European economies. There was considerable interest in Australia’s experience with the housing cycle and other developments in the dollar bloc periphery.

While I was away, Treasurer Costello used the Hendy-Warburton report to remind us how wonderful the Australian taxation system is in comparison with the rest of the OECD. Having just visited some of the other OECD countries in question, I’m even more unmoved than usual by such lame comparisons.

The Treasurer’s accompanying press release noted that “The Report will stand as a significant reference point to assist in framing policy to improve taxation policy.” Yet the press release does not explicitly identify a single area in which Australian tax policy might actually be lacking.

posted on 27 April 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

There will be no posts over the next three weeks while I take a break. Comments will be closed and new member/comment registrations queued for approval at a later date. I will not be responding to email.

posted on 03 April 2006 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink

Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy as fig leaves for Treasury:

Late last month, the Treasurer appointed leading business figures Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy to conduct a study comparing Australia’s tax competitiveness with other nations.

But The Australian has learned that almost all the work is being done by a team of nine Treasury officials who are conducting the research and drafting the report in order to meet the April 3 deadline set by Mr Costello.

It is understood that the Treasury team has been sending Mr Warburton, the chairman of Caltex Australia and a former Reserve Bank director, and Mr Hendy, the chief executive of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, drafts of chapters detailing their conclusions for the authors’ comments.

But it is understood Treasury failed to include some of the authors’ amendments and suggested changes in revised drafts.

Mr Warburton admitted yesterday that the report was being written by Treasury officials but said any comments he believed should be included would be in the report. “Peter Hendy and I would not have the time to write this material,” he told The Australian.

He defended the process as necessary given the tight deadline set by Mr Costello, which will allow the Treasurer to consider its findings before making any changes to the tax system in the May budget.

Mr Warburton and Mr Hendy were reviewing Treasury’s work yesterday, four days before the report’s Monday deadline.

Mr Warburton denied that the review’s independence was compromised by Treasury’s role in sourcing the evidentiary material. He agreed those involved in the review were working “long hours” but denied an overseas trip he is due to make next week had compromised the inquiry.

posted on 31 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink

Should we be surprised when an adjunct scholar at a supposedly free market US think-tank writes a piece calling for regulatory attacks and litigation against mobile phone users and companies, simply because the author finds mobile phone use annoying?

This is what the AEI’s Jagdish Bhagwati proposes in an article in the FT. Bhagwati compares mobile phone use to bird flu, suggests mobile phone users are breaching human rights conventions and then turns vindictive, saying:

If providence were just, it would surely affect the brains of the users.

Bhagwati is a long-standing apologist for capital controls, belying his reputation as a defender of free trade and globalisation. He is also clearly neurotic.

posted on 30 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

It is not often you can dismiss a forecast as soon as it’s made, but Nouriel Roubini’s latest bit of doom-mongering is DOA. Nouriel suggests that Australia and New Zealand, among others, are set to experience a disruptive currency and financial crisis:

Runs on currency and liquid local assets may still occur with severe and disruptive effects on currency values, bond markets, equity markets and the housing market.

In the case of Australia and New Zealand, this prospect can be dismissed out of hand (I wouldn’t necessarily make this claim for some of the emerging market economies Nouriel lumps in with Australia and NZ). The best evidence against Roubini’s scenario is the experience of both countries in 2001, when the Australian and NZ dollars fell below 0.5000 and 0.4000 respectively. Not only was there no significant disruption to the domestic economy and financial markets of either country, the boost to competitiveness added to the strength of both economies. Nouriel’s assumption that a falling currency woud lead to a dumping of local currency-denominated assets by foreign investors didn’t play out then, not least because many foreign investors are significantly hedged against currency risk. The Australian and NZ dollars are currently falling in part because their debt markets are outperforming the US. If anything, a cheaper currency makes local asset markets even more attractive to fresh inflows of foreign capital.

In recent months, New Zealand authorities have not only welcomed a falling currency, they have even been actively trying to scare-off foreign investors - hardly the actions of a government worried about a currency crisis. The main risk to the NZ economy has been the domestic policy tightening that had seen the NZD trade weighted index to post-float record highs at the end of last year. An exchange rate driven easing in overall monetary conditions is exactly what NZ needs right now.

Roubini’s forecast in relation to Australia and NZ is also difficult to square with his bearishness on the US dollar. According to Nouriel:

U.S. policymakers - both at Treasury and even some, but not all, at the Fed - live in this LaLa Land dream that the U.S. current account deficits and fiscal deficits do not matter and that the U.S. external deficit is all caused by a global savings glut or is actually a “capital account surplus” as it allegedly represents the foreigners’ desire to hold U.S. assets. They - and financial markets and investors - may soon wake up from this unreal dream and face a nightmare where the U.S. looks like Iceland more than they have ever fathomed.

Roubini would have us believe that both the US dollar and the dollar bloc peripheral currencies are at risk, yet this would imply that the AUD-USD and NZD-USD exchange rates should remain relatively stable. It is even harder to envisage an Australian and NZ currency or financial crisis, when the most important exchange rate, that with the US, is largely stable.

Nouriel is the one living in LaLa Land.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink

While Peter Costello waits on the results of his international tax beauty contest, Andrew Ball in the FT (via The Australian) notes a recent paper by Eijffinger and Geraats, which:

found that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of England were the most transparent central banks. Next came the Bank of Canada, the European Central Bank and the Fed. Bringing up the rear were the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank.

The paper notes the RBA’s many shortcomings:

Although the Reserve Bank of Australia has adopted inflation targeting, it gets one of the lowest transparency scores (8, increasing to 9 in 2002) in our sample. Although the RBA gets the maximum score on political transparency, its openness on other aspects is much less. Economic transparency falls short because it does not publish quarterly data on capacity utilization and only provides rough short term forecasts for inflation (quarterly) and output (semiannually) without numerical details about the medium term. In addition, there was no explicit policy model until October 2001. Procedural transparency is low as the RBA does not release minutes and voting records. There is also scope for greater policy transparency because of the lack of an explicit policy inclination and a prompt explanation of each policy decision. Regarding operational transparency, the RBA provides neither a discussion of past forecast errors, nor an evaluation of the policy outcome. The Reserve Bank of Australia shows that inflation targeting by no means guarantees transparency in all respects.

The RBA’s published policy model (updated late last year) still carries the formal disclaimer that it does not represent the views of the RBA, so it is questionable whether it qualifies as an explicit policy model.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink

Page 87 of 111 pages ‹ First < 85 86 87 88 89 > Last ›

|