A Beginners Guide to Oil

A review of Vaclav Smil’s new book, Oil:

The list of big-name economists, commentators and forecasters who hung their hats—and their investment plans—on variations of peak oil theory is too big for this page, but some day somebody should post it prominently for all to see.

One of the rare exceptions, a name not on any such list, is Vaclav Smil, perhaps one of Canada’s greatest unsung academics. Let me now sing his praises. Prof. Smil is a distinguished professor in the environment faculty at the University of Manitoba. One of his many books, usually dense and written for scholars, is a new popular Beginners Guide, simply titled Oil (Oneworld Publications, 200 pages, 2008).

Back in June, 2006, Prof. Smil wrote a commentary for FP Comment dismissing the peak oil crowd as a “new catastrophist cult.” In 2000, he warned in a science journal that the experience of long-range forecasting, especially in energy, had been dismal. He predicted more. “There will be no end to naive, and ... incredibly short-sighted or outright ridiculous, predictions.”

Prof. Smil’s new contribution to the absurdity of peak oil theory, Oil, is more than just a critique of the latest crackpot forecasting theories. In 200 pages, he packs everything most people—including most economists and investment advisors—should know about the physics and economics of oil.

As time goes on the world will slowly sever its dependence on fossil fuels, but any such transition is decades away. Peak oil enthusiasts are wrong for scores of reasons. They assume that oil reserves are know with some degree of precision; that reserves are fixed; that demand and supply can be projected with accuracy over long periods of time.

As Prof. Smil wrote on this page in 2006: “Unless we believe, preposterously, that human inventiveness and adaptability will cease the year the world reaches the peak annual output of conventional crude oil, we should see that milestone (whenever it comes) as a challenging opportunity rather than as a reason for cult-like worries and paralyzing concerns.”

posted on 12 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Oil

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Will the Euro Survive the Crisis?

Martin Feldstein asks whether the euro can weather the global financial crisis:

The current differences in the interest rates of euro-zone government bonds show that the financial markets regard a break-up as a real possibility. Ten-year government bonds in Greece and Ireland, for example, now pay nearly a full percentage point above the rate on comparable German bonds, and Italy’s rate is almost as high.

There have, of course, been many examples in history in which currency unions or single-currency states have broken up. Although there are technical and legal reasons why such a split would be harder for an EMU country, there seems little doubt that a country could withdraw if it really wanted to.

The most obvious reason that a country might choose to withdraw is to escape from the one-size-fits-all monetary policy imposed by the single currency. A country that finds its economy very depressed during the next few years, and fears that this will be chronic, might be tempted to leave the EMU in order to ease monetary conditions and devalue its currency. Although that may or may not be economically sensible, a country in a severe economic downturn might very well take such a policy decision.

Intrade puts the probability of an existing member leaving the eurozone before the end of 2010 at 27%.

posted on 11 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How Not To Solve a Crisis

The Lion Rock Institute and International Policy Network have published a report by Bill Stacey and Julian Morris on How Not to Solve a Crisis. I agree with their assessment of the failure to bail out Lehman Brothers, which runs counter to the conventional wisdom:

The Lehman bankruptcy followed on 15 September, after talks with a few parties about a buyout failed. Early talks apparently failed because management held out for a higher price. Later talks failed because the government refused the guarantees sought by potential purchasers. The consequences of failure were large, with unsettled trades and frozen collateral disrupting markets everywhere. The Bear precedent had led many market participants to believe that Lehman would not be allowed to fail. Markets quickly priced the swing in policy, leaving all securities companies vulnerable.

The popular view among market participants is that Lehman should not have been allowed to fail. Yet if Bear had not earlier been rescued, Lehman would likely earlier have raised funds, counterparties would have more quickly protected themselves from risks and underlying problems would have been recognized sooner.

posted on 10 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

One Speech, Two Stories

The Australian:

RESERVE Bank governor Glenn Stevens last night flagged further interest rate cuts to help shore up the economy.

The AFR:

Reserve Bank Governor Glenn Stevens has signalled the bank’s unprecedented series of deep interest rate cuts may have come to an end.

Both papers fell victim to the view that every time the Governor speaks, he must be sending a signal on interest rates and if there is no explicit signal, then there must be an implied one. In fact, the RBA very rarely signals its policy intentions, not least because its view on the future direction of policy is not very strongly held. Unlike the rest of us, the RBA doesn’t need to anticipate its own actions, putting more value on policy flexibility than policy predictability.

posted on 10 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Why Stimulus Measures Don’t Work

I have an op-ed in today’s Age, highlighting the Ricardian and open economy macro arguments against using fiscal policy for demand management:

From the perspective of national saving, it makes no difference whether an increase in government spending comes out of the budget surplus or whether the government goes into deficit and borrows from capital markets. Either way, the government is saving less.

But this doesn’t mean that households will follow the government’s example. In fact, households are likely to save more in anticipation of a higher future tax burden due to the reduction in government saving…

Demand management is best left to the Reserve Bank and monetary policy, which has already responded aggressively to a slowing economy.

The sharp decline in the Australian dollar exchange rate is also a powerful stimulus to net exports, but any boost to demand from fiscal stimulus will also have the perverse effect of putting upward pressure on the exchange rate, reducing net exports. In an open economy, there is no free lunch from fiscal policy.

Fiscal policy still has a role to play in supporting economic growth, but it needs to focus on long-run structural and supply-side issues not short-term attempts at rigging aggregate demand.

This means rewarding labour force participation, not encouraging welfare dependence. Throwing more money at pensioners and families will not boost economic growth in the long-run and may not work as the government intends in the short-run.

In The Australian, Henry Ergas makes a similar argument against proposals to use superannuation contributions as a macroeconomic stabilisation instrument:

Consumption decisions are shaped not by transient changes in income but by expectations of income going forward, a proposition known as the permanent income hypothesis. A short-term reduction in compulsory savings, soon reversed and followed by a sequence of rapid increases in mandatory contributions, amounts to a pre-announced reduction in disposable incomes. As households respond to the news that their disposable incomes will fall once the temporary cut is reversed, consumption is likelier to decline than to increase.

My Age piece may have fallen victim to a which-hunt. This line should read:

‘The household saving ratio has already surged from 1.3% in the June quarter to 3.9% in the September quarter. This implies that taxpayers squirreled away their 1 July tax cuts, which came at the expense of the budget surplus rather than cuts to government spending. ‘

posted on 10 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(6) Comments | Permalink | Main

Saved Not Spent: Ricardian Equivalence Negates Fiscal Stimulus

Westpac crunches the numbers on the household income account, with some predictable results:

All up, the total fiscal boost to household disposable income in Q3 was about $1.9bn. This was mostly due to $7.1bn in income tax cuts, which equates to $1.8bn a quarter. The boost appears to have done little or nothing to stimulate consumer spending in Q3. Indeed, with aggregate household savings rising by $4.4bn in the quarter, the implication is that, in aggregate, households saved all of the windfall and then some. Most of the savings appears to have gone towards paying down housing debt.

The national accounts figures and RBA credit data imply that households injected an enormous $7.5bn into their housing equity in Q3, most of which would have been via paying down principal. This is only the third net equity injection recorded since June 2001. It is easily the largest ever in dollar terms and is the biggest as a proportion of income since 1998Q3. If Q3 is a guide and households remain as deeply concerned about reducing their debt levels in the months ahead, the implication is that there will be little or no boost from policy stimulus in Q4.

Westpac nonetheless thinks Q4 might be different, on the basis that saving all the stimulus in Q4 would be ‘too extreme’, but unprecedented times are likely to induce unprecedented responses as households anticipate a higher future tax burden.

posted on 04 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

Why Falling Commodity Prices May be Good for Growth

The Australian economy expanded 0.1% in the September quarter, which is dismal enough, but non-farm GDP contracted 0.3% over the quarter. Farm output rose 14.9% over the quarter. In current prices, the increase was only 7.5%, but the price deflator for farm GDP fell 6.5% over the quarter.

This points to a little appreciated aspect of the relationship between commodity prices and the Australian economy. High commodity prices are often the flip side of weak commodity production, which depresses real GDP growth. To the extent that lower commodity prices reflect increased output, this is actually a positive for real GDP growth.

As I argue in a forthcoming article in Policy, commodity prices are far less important to economic growth in Australia than conventionally assumed.

posted on 03 December 2008 by skirchner in Commodity Prices, Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Did the Australian Economy Contract over the September Quarter?

The consensus forecast for September quarter GDP growth to be released on Wednesday is 0.2%, with growth through the year seen at 1.9%. Market forecasts range from -0.3% q/q to 0.5% q/q. Dusting off the old top-down GDP model, I also get 0.2% q/q.

Growth would then have to accelerate slightly to 0.3% in the December quarter to be consistent with the RBA’s year-end forecast of 1.5%. That may be a tall order given what is happening both domestically and globally, but by no means impossible.

The market is expecting a 75 bp reduction in the official cash rate to 4.5% tomorrow. With the RBA’s forecast for underlying inflation for the December quarter at 4.5%, the real cash rate will effectively be zero.

posted on 01 December 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Foreign Oil is Your Friend

Roger Howard, author of The Oil Hunters, on how foreign oil creates interdependence rather than dependence:

to identify America’s “foreign oil dependency” as a source of vulnerability and weakness is just too neat and easy.

This identification wholly ignores the dependency of foreign oil producers on their consumers, above all on the world’s largest single market—the United States. Despite efforts to diversify their economies, all of the world’s key exporters are highly dependent on oil’s proceeds and have always lived in fear of the moment that has now become real—when global demand slackens and prices fall. The recent, dramatic fall in price per barrel—now standing at around $54, less than four months after peaking at $147—perfectly exemplifies the producers’ predicament.

So even if such a move were possible in today’s global market, no oil exporter is ever in a position to alienate its customers. Supposed threats of embargoes ring hollow because no producer can assume that its own economy will be damaged any less than that of any importing country. What’s more, a supply disruption would always seriously damp global demand. Even in the best of times, a prolonged price spike could easily tip the world into economic recession, prompt consumers to shake off their gasoline dependency, or accelerate a scientific drive to find alternative fuels. Fearful of this “demand destruction” when crude prices soared so spectacularly in the summer, the Saudis pledged to pump their wells at full tilt. It seems that their worst fears were realized: Americans drove 9.6 billion fewer miles in July this year compared with last, according to the Department of Transportation.

Instead, the dependency of foreign oil producers on their customers plays straight into America’s strategic hands.

posted on 29 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Oil

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Robertson-Keen Wager

Rory Robertson gets ready to send Steve Keen on a long walk:

To make it interesting, I offered Dr Keen a challenge…

On the maybe 1% chance that he is right, and capital-city home prices do indeed fall by 40% within the next five years - starting from Q2 2008, and as measured by the ABS - I will walk from Canberra to the top of Mt Kosciusko (that’s maybe 200km followed by a 2228-metre incline).

If Dr Keen turns out to be less than half right, as I expect, and home prices drop by (much) less than 20%, he will take that long walk. Moreover, the loser must wear a tee-shirt saying: “I was hopelessly wrong on home prices! Ask me how.”

We now have a bet, and I expect to record an easy win within two years.

posted on 28 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

Capital Xenophobia II

The Centre for Independent Studies has released my Policy Monograph Capital Xenophobia II: Foreign Direct Investment in Australia, Sovereign Wealth Funds and the Rise of State Capitalism.

The monograph revisits the subject of Wolfgang Kasper’s original 1984 Capital Xenophobia monograph. Wolfgang was kind enough to write the foreword to this update of his earlier work on the subject.

There is an op-ed version in today’s AFR for those who have access, reproduced below the fold for those who don’t (text may differ slightly from the edited AFR version).

continue reading

posted on 27 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Why Was Fed Policy ‘Too Easy’ Between 2002 and 2005?

Larry White has a new Cato Briefing Paper How Did We Get into This Financial Mess? White echoes a now widespread criticism of US monetary policy, that is was too easy in the first half of this decade:

The federal funds rate began 2001 at 6.25 percent and ended the year at 1.75 percent. It was reduced further in 2002 and 2003, inmid-2003 reaching a record low of 1 percent, where it stayed for a year. The real Fed funds rate was negative - meaning that nominal rates were lower than the contemporary rate of inflation - for two and a half years.

White also notes that the Fed funds rate was below that implied by the Taylor rule, a point that Taylor himself has also made.

That US monetary policy was easy at this time was no accident. It was a very deliberate policy choice on the part of the FOMC. Why was policy kept so easy for so long? One reason was the perceived threat of deflation, as Vince Reinhart recalls:

According to FOMC meeting transcripts from that year, then Chairman Alan Greenspan in November [2002] called deflation “a pretty scary prospect, and one that we certainly want to avoid.”

Then Gov. Ben Bernanke, now Fed chairman, said in September 2002, “the strategy of preemptive strikes should apply with at least as great a force to incipient deflation as it does to incipient inflation.”

In hindsight while there was clearly a strong disinflation trend back then, outright deflation didn’t appear to be as big a risk as the Fed thought. Annual growth in consumer prices never fell below 1% and was rarely below 2% after 2002.

The problem back then, Reinhart said, was “we didn’t know why inflation was going down as much as it was.”

That year, 2002, “was very much a story of uncertainty about the inflation process with some modest identifiable forces putting downward pressure” on prices, he said.

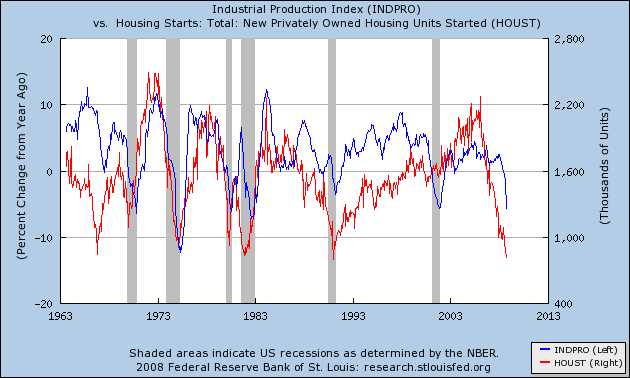

This puts the failure of US monetary policy to respond to the emerging US housing boom in its proper context. The following chart shows annual growth in US industrial production as a proxy for the broader economy, along with new privately-owned dwelling starts as a proxy for housing activity. Shaded bars are NBER-defined recessions.

The 2001 recession was exceptional compared to previous business cycles, in that housing activity did not see a significant downturn along the rest of the US economy. Industrial production was subdued coming out of the 2001 recession (note the double dip into negative growth), while housing continued to enjoy a strong expansion. If the 2001 recession could not tame the US housing boom, then it is hard to see how tighter US monetary policy could have done so without inflicting significant, and potentially deflationary, collateral damage on the rest of the economy.

One could argue that Fed policy was a success on its own terms, because it achieved exactly what it set out to do: pre-empt the threat of deflation.

posted on 21 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(35) Comments | Permalink | Main

Has the RBA Given the ‘Green Light’ to ‘Bubble’ Popping?

RBA Governor Glenn Stevens’ speech to CEDA last night has been widely interpreted as giving a ‘green light’ to deficit spending, as if politicians ever needed permission or encouragement from the Reserve Bank to ramp-up spending. The really significant part of Stevens’ speech went largely unnoticed:

in addition to the many useful steps being planned by regulators, perhaps we could pay more attention to the low-frequency swings in asset prices and leverage (even if that means less attempt to fine-tune short-period swings in the real economy); we could have a more conservative attitude to debt build-up; and we could exhibit a little more scepticism about the trade-off between risks and rewards in rapid financial innovation. This would constitute a useful mindset for us all to take from this episode.

The fudge word here, of course, is ‘more.’ More could simply mean giving greater weight to the implications of developments in asset prices for inflation and the overall economy. However, it could potentially extend much further, to an attempt by central bankers to actively manage asset prices at the expense, as Stevens suggests, of shorter-run demand management. As I argue here, the historical precedents for this are far from encouraging.

A more recent example of a central bank conditioning monetary policy on asset prices was the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s use of the trade-weighted exchange rate as part of a composite operating target between 1996 and 1999, known as the monetary conditions index. This practice was abandoned, because the well-known volatility of exchange rates and their very loose relationship with economic fundamentals made it a very poor basis for conducting monetary policy. The weaker the connection between asset prices and economic fundamentals, the stronger the argument against using asset prices as either targets or conditioning variables for monetary policy.

posted on 20 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

Software Update

The software that runs Institutional Economics has been updated. Please let me know if you experience any problems: info at institutional-economics.com. This site is powered by ExpressionEngine.

posted on 15 November 2008 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Regulating Ratings Agencies

The federal government is proposing to further regulate credit ratings agencies:

The Government also unveiled changes to the regulation of credit ratings agencies that will require them to hold an Australian Financial Services Licence and to report annually on the quality and integrity of their ratings processes.

The changes reflect a growing demand in the global investment community for greater oversight of ratings agencies, which have become the target of criticism, particularly for their role in rating structured finance.

This ignores the somewhat inconvenient truth that the role of ratings agencies in credit markets was itself mandated by regulation. As Charles Calomiris has argued, the regulatory power given to the ratings agencies encouraged them to compete on relaxing the cost of regulation to investors, generating huge fees for the ratings agencies in the process. Calomiris summed it up this way: ‘the regulatory use of ratings changed the constituency demanding a rating from free-market investors interested in a conservative opinion to regulated investors looking for an inflated one.’ Calomiris notes that both Congress and the SEC actually encouraged ratings inflation in relation to sub-prime CDOs, an unintended consequence of their promotion of rules designed to prevent ‘anti-competitive’ behaviour on the part of the dominant ratings agencies.

posted on 14 November 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 52 of 111 pages ‹ First < 50 51 52 53 54 > Last ›

|