2009 11

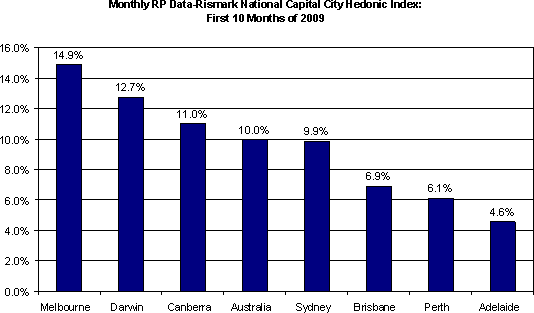

RP Data-Rismark have released the capital city hedonic house price index for October, showing house prices up 10% YTD.

Here’s what $1.85 million buys you in the Sydney suburb of Paddington:

posted on 30 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Michael Stutchbury quotes Warwick McKibbin on the likely consequences of Labor’s emissions trading scheme:

Economist and Reserve Bank of Australia board member Warwick McKibbin warns the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme is “fundamentally unstable”, the price of permits will be “inherently volatile” and the Copenhagen agenda is in “total disarray”. “The political fallout from this is going to lead to changes,” he says.

The Coalition should let Kevin Rudd have full ownership of the fallout.

posted on 28 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Tony Abbott offers support for a carbon tax as an alternative to an ETS in today’s Australian:

many respected economists think a carbon tax would be more certain, less complex and far less open to manipulation than traded carbon permits.

In government, Malcolm Turnbull showed considerable interest in Warwick McKibbin’s proposal for a hybrid ETS-carbon tax. This story from February 2007 (’Turnbull gives tick to McKibbin carbon trading model’) quotes McKibbin as saying that Turnbull ‘understands it completely’, which makes Turnbull’s subsequent support for Labor’s ETS all the more inexcusable.

The Liberals who support Labor’s ETS do so largely because they are too lazy to argue for the alternative policy approaches they know to be better. I have heard several Liberal frontbenchers maintain that any policy with the word ‘tax’ in it won’t gain political support. They support an ETS only because they want to neutralise climate change as a political issue, not because they believe it to be the best policy. This is a monumental failure of leadership.

An obvious way forward for the Liberal Party, and for the Coalition, would be to commission McKibbin to design a hybrid scheme to take to the next election as an alternative to Labor’s ETS.

UPDATE: Joe Hockey goes begging for ideas on Twitter:

Hey team re The ETS. Give me your views please on the policy and political debate. I really want your feedback.

As David Cameron once said, too many tweets make a twat.

posted on 27 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Deputy Governor Ric Battellino, on why the housing investment share of GDP will have to rise.

posted on 26 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Chinese garlic.

posted on 26 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Brendan O’Neill, on why Malthusians are always wrong.

posted on 25 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Gold is all about capital gain (or loss, as the case may be). After storage and insurance costs, gold has a negative yield. These costs may be about to go up, with retail gold bugs being booted out of gold storage facilities to make way for institutional investors. From the WSJ:

Amid gold’s rise—it has gained 32% this year and reached a record on Monday—investors have been loading up on bullion and coins. One big problem now is where to store it. The solution from HSBC, owner of one of the biggest vaults in the U.S.: somewhere else.

HSBC has told retail clients to remove their small holdings from its fortress beneath its tower on New York City’s Fifth Avenue. The bank has decided retail customers aren’t profitable enough and is demanding those clients remove their gold to make room for more lucrative institutional customers…

HSBC’s decision has created a logistical nightmare for both the investors and the security teams in charge of relocating the gold, silver and platinum to new vaults across the country…

HSBC is telling clients to either move their metal, or prepare for it to be delivered to their doorsteps. In a July letter, seen by The Wall Street Journal, HSBC said the precious metal “will be returned to the address of record… at your expense,” unless instructed otherwise. HSBC recommended clients move their holdings to Brink’s Global Services USA Inc., which has a vault in Brooklyn, N.Y.

posted on 25 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Gold

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Wall Street Journal has been running a series of articles on the impact of US dollar weakness on Asia-Pacific economies. In today’s edition, I write about New Zealand Labour’s abandonment of the consensus on inflation targeting:

Mr. Goff’s criticism of this dynamic misses the important benefits inflation targeting and its effects on the exchange rate bring to New Zealand. The dollar’s fluctuations help insulate the economy from external shocks, not least during the recent global financial crisis. When demand weakens in the rest of the world, the New Zealand dollar depreciates, making New Zealand’s exports more competitive. When external demand is strong, the currency rises, moderating export prices in New Zealand-dollar terms and restraining import price inflation. New Zealand’s floating exchange rate thus smoothes external demand and economic activity, making the central bank’s job of controlling inflation much easier.

Many exporters resent the role of the exchange rate in moderating New Zealand’s economic cycle, viewing their competitiveness as being sacrificed on the altar of inflation control. But the idea that New Zealand can ignore inflation and grow faster through easy money and a lower exchange rate is a short-sighted view, no matter how tempting. It ignores the fact that higher domestic prices resulting from inflation would ultimately undermine rather than promote international competitiveness. Economic growth and export success must ultimately be built on real factors such as productivity growth, not easy money and exchange rate depreciation.

Sinclair Davidson made similar arguments in relation to the Australian dollar in an earlier op-ed in the series.

posted on 23 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

The leader of the opposition New Zealand Labour Party, Phil Goff, has announced the abandonment of his party’s support for inflation targeting by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

It was a Labour government that introduced the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act in 1989, making New Zealand a global pioneer in the practice of inflation targeting.

I have long suspected that the global trend towards increased central bank independence and inflation targeting would eventually be reversed. As I noted in my Bubble Poppers monograph, even the central banking community is increasingly divided on the issue.

If the bipartisan consensus in favour of inflation targeting can be shattered in New Zealand, it can happen anywhere.

posted on 19 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

With the nominal US dollar gold price posting record highs, I have an op-ed in today’s Age discussing the role of central banks and exchange rates in the determination of the gold price. Gold is a stock rather than a flow equilibrium and central banks command a large share of global stocks. However, exchange rates also have a large influence on the local currency returns to gold:

US dollar weakness has a positive valuation effect on the US dollar gold price, in the same way that it makes oil more expensive in US dollar terms. While a rising US dollar gold price is seen as symptomatic of a declining US dollar, this is true of US dollar commodity prices more generally.

Like other commodities, gold’s gains look less impressive in terms of currencies other than the US dollar. The Australian dollar exchange rate is positively correlated with the US dollar gold price, so that gains in US dollar terms are usually offset by Australian dollar appreciation. For an Australian investor, gold may be a good hedge against Australian dollar weakness, but actually increases exposure to US dollar weakness.

posted on 17 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Gold

(5) Comments | Permalink | Main

The CIS have released my Policy Monograph on Reforming Capital Gains Tax: The Myths and Realities Behind Australia’s Most Misunderstood Tax. There is an op-ed version in today’s Australian.

The 2004 Productivity Commission inquiry into first home ownership noted that ‘changes to the capital gains tax regime coupled with longstanding negative-gearing arrangements were seen to have contributed to higher prices through encouraging greater investment in housing’, but the commission did not model the effects of the tax changes. If increased investment is putting upward pressure on prices, this is an argument for easing supply-side constraints, not for discouraging investment with a CGT. CGT is a tax on transactions that would reduce turnover in owner-occupied housing and lead to a less efficient allocation of that stock.

Some mistakenly see a CGT on the family home as a way of soaking the rich. Yet a CGT on owner-occupied housing would most likely be accompanied by tax deductibility for mortgage interest payments, as in the US, offsetting any increase in revenue from a CGT.

In conjunction with negative gearing, the Ralph reforms were blamed for the housing boom in Australia in the early part of this decade. In reality, the boom was caused by the inability of housing supply to respond flexibly to the increased debt-servicing capacity of households in a low inflation, low interest rate environment.

The boom in house prices also occurred in the context of a bear market in equities between 2001 and 2003. It is not surprising demand for housing increased when prices of a competing asset class were declining. House price inflation was a global phenomenon, arguing against country-specific factors as the main cause.

Rather than increasing the tax burden on housing, policymakers need to tackle the impediments to new housing supply to improve affordability.

posted on 12 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy, House Prices

(5) Comments | Permalink | Main

An illustrated history of Nouriel’s money-losing calls of 2009.

posted on 11 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Board member Warwick McKibbin, on the resource cost of fiscal stimulus:

RESERVE Bank director Warwick McKibbin has publicly questioned whether the Rudd government dumped him from the Prime Minister’s science council as payback for saying its fiscal stimulus package was “too big”.

Speaking yesterday after Wayne Swan said the RBA was “entirely comfortable with our fiscal policy”, Professor McKibbin said he had no doubt history would show that the Rudd government had overdone the stimulus.

Professor McKibbin also revealed that part of the motivation behind establishing a new council of eminent economists to debate policy issues was to encourage academics to speak out.

“I think when people look through the entrails of this, they will find billions, if not tens of billions, that was just lost,” he told The Australian.

A few weeks after he suggested that the second part of the stimulus package was too large while giving evidence at a Senate inquiry in May, he was dumped from a government advisory role on the Prime Minister’s Science and Innovation Council, Professor McKibbin said.

posted on 09 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The US Treasury has been running high level briefing sessions for economic bloggers. Officialdom has obviously recognised that bloggers are an influential voice and need to be managed like old media. Fortunately, economics bloggers are proving a little more spin-resistant than Treasury perhaps expected. Here is what Naked Capitalism thought about the briefing:

It wasn’t obvious what the objective of the meeting was (aside the obvious idea that if they were nice to us we might reciprocate. Unfortunately, some of us are not housebroken).

And Steve Waldman:

The second thing I’d like to discuss is corruption. Not, I hasten to add, the corruption of senior Treasury officials, but my own. As a slime mold with a cable modem, it was very flattering to be invited to a meeting at the US Treasury. A tour guide came through with two visitors before the meeting began, and chattily announced that the table I was sitting at had belonged to FDR. It very clearly was not the purpose of the meeting for policymakers to pick our brains. The e-mail invitation we received came from the Treasury’s department of Public Affairs. Treasury’s goal in meeting with us was to inform the public discussion of their past and continuing policies. (Note that I use the word “inform” in the sense outlined in a previous post. It is not about true or false, but about shaping behavior.)

Nevertheless, vanity outshines reason, and I could not help but hope that someone in the bowels of power had read my effluent and decided I should be part of the brain trust. The mere invitation made me more favorably disposed to policymakers. Further, sitting across a table transforms a television talking head into a human being, and cordial conversation with a human being creates a relationship. Most corrupt acts don’t take the form of clearly immoral choices. People fight those. Corruption thrives where there is a tension between institutional and interpersonal ethics. There is “the right thing” in abstract, but there are also very human impulses towards empathy, kindness, and reciprocity that result from relationships with flesh and blood people. That, aside from “cognitive capture”, is why we should be wary of senior Treasury officials spending too much time with Jamie Dimon. It is also why bloggers might think twice about sharing a conference table with masters of the universe, public or private. Although the format of our meeting did not lend itself to forging deep relationships, I was flattered and grateful for the meeting and left with more sympathy for the people I spoke to than I came in with. In other words, I have been corrupted, a little.

In Australia, it is worth noting that most of the running on the issue of RBA media backgrounding has been from new media like Business Spectator and bloggers, although old media have since picked-up the story too. Spin control becomes a lot more difficult when dealing with a proliferation of unregulated media with no stake in the status quo.

posted on 06 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

I have an op-ed in the business section of today’s Australian on the future of the US dollar (no link, but full text below the fold). Many commentators mistakenly view the market-clearing price of the US dollar on foreign exchange markets as a reflection on the US dollar’s future role in the international financial system. As I argue in my op-ed, the US dollar’s role is entirely a function of the role of US capital markets in the international financial system. It makes the often neglected point that a declining US dollar actually improves the net international investment position of the United States.

I would also highly recommend Richard Cooper’s PIIE Policy Brief on The Future of the Dollar. Cooper is particularly good in explaining why it is China that is financially dependent on the US, not the other way around.

continue reading

posted on 05 November 2009 by skirchner

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Eugene Fama reviews The Myth of the Rational Market, by Justin Fox:

The book is fun reading, but its main premise is fantasy. Most investing is done by active managers who don’t believe markets are efficient. For example, despite my taunts of the last 45 years about the poor performance of active managers, about 80% of mutual fund wealth is actively managed. Hedge funds, private equity, and other alternative asset classes, which have attracted big fund inflows in recent years, are built on the proposition that markets are inefficient. The recent problems of commercial and investment banks trace mostly to their trading desks and their proprietary portfolios, and these are always built on the assumption that markets are inefficient. Indeed, if banks and investment banks took market efficiency more seriously, they might have avoided lots of their recent problems. Finally, MBA students who aspire to high paying positions in the financial industry have a tough time finding a job if they accept the EMH.

I continue to believe the EMH is a solid view of the world for almost all practical purposes. But it’s pretty clear I’m in the minority. If the EMH took over the investment world, I missed it.

The Fox book is an example of a general phenomenon. Finance, financial markets, and financial institutions are in disrepute. The popular story is that together, they caused the current recession. I think one can take an entirely different position: financial markets and financial institutions were casualties rather than the cause of the recession.

posted on 05 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

An insight into how Australia is perceived abroad, care of Holman Jenkins in the WSJ:

What most infuriated their hosts, though, was Telstra’s abandonment of its traditional deference to policy makers. The company took regulators to court over mandates requiring it to lease its network to competitors at knockdown rates. Mr. Burgess bashed civil servants and politicians by name, in a fashion apparently deemed unbecoming a corporate citizen in Australia…

Australia lacks America’s bottomless think-tank and K Street resources for publicizing policy differences. Its parliamentary government puts all the policy levers, including a ready resort to secrecy, in the ruling party’s hands. Australia is a small nation, with a small elite that tends to place limits on burn-the-bridges debate.

posted on 04 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Following the release of the ABS house price data for the September quarter, Steve Keen concedes defeat in his bet with Rory Robertson and will be hiking from Canberra to the top of Australia’s highest mountain wearing a teeshirt that reads ‘I was hopelessly wrong on house prices, ask me how.’ Keen’s answer is to blame the gub’nent:

“I didn’t know the government was going to be stupid enough to bring in the first home buyer’s boost”.

While I would agree that the increased first home-owners grant has inflated house prices, transferring wealth from taxpayers to incumbent property owners, it would be an exaggeration to say that this prevented a decline in house prices of the magnitude Keen has been predicting. Moreover, any forecast needs to discount the likely actions of policymakers.

Steve Keen has inadvertently supplied yet another observation in favour of the efficient market hypothesis, much like Robert Shiller’s suggestion in 1996 that investors should stay out of the stock market for the following decade. The EMH maintains only that we cannot predict future innovations in asset prices. It is ironic that both Keen and Shiller have demonstrated the truth of this proposition in the course of trying to refute it.

Perhaps the teeshirt should read, ‘The EMH was right on asset prices, just don’t ask me how’.

posted on 03 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, House Prices

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

I featured in a Lateline Business story last night on Reserve Bank media backgrounding in relation to monetary policy. Lateline Business supervising producer Richard Lindell deserves considerable credit for pursuing this story in the face of both official and unofficial stonewalling. Credit is also due to Alan Kohler, Adam Carr and Christopher Joye, who have all spoken out on this issue. Some of the people who originally agreed to appear on camera for the story were prevented from doing so by their employers. As I said to Richard Lindell, ‘now you know why market economists don’t criticise fiscal stimulus.’

A 2001 AFR Magazine profile of then RBA Governor Ian Macfarlane by Peter Hartcher quoted a former RBA official as saying:

The Bank uses newspapers to manage expectations. It’s a game the Bank manages very well. Senior people talk to a small handful of the economics writers from the major papers on a strictly non-attributable basis.

The quote was re-produced in Stephen Bell’s 2004 book on the Reserve Bank, Australia’s Money Mandarins (see my review). Journalists and academics should be the standard-bearers for due process, procedural fairness and public accountability. Yet many commentators view the RBA’s manipulation of the media as simply a clever use of power.

The practice is a legacy of a less transparent era at the Reserve Bank. With so many open channels of communication now available to the Bank, there is no longer any excuse for it to continue.

There is more on Reserve Bank governance here.

posted on 03 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

|