2006 03

Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy as fig leaves for Treasury:

Late last month, the Treasurer appointed leading business figures Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy to conduct a study comparing Australia’s tax competitiveness with other nations.

But The Australian has learned that almost all the work is being done by a team of nine Treasury officials who are conducting the research and drafting the report in order to meet the April 3 deadline set by Mr Costello.

It is understood that the Treasury team has been sending Mr Warburton, the chairman of Caltex Australia and a former Reserve Bank director, and Mr Hendy, the chief executive of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, drafts of chapters detailing their conclusions for the authors’ comments.

But it is understood Treasury failed to include some of the authors’ amendments and suggested changes in revised drafts.

Mr Warburton admitted yesterday that the report was being written by Treasury officials but said any comments he believed should be included would be in the report. “Peter Hendy and I would not have the time to write this material,” he told The Australian.

He defended the process as necessary given the tight deadline set by Mr Costello, which will allow the Treasurer to consider its findings before making any changes to the tax system in the May budget.

Mr Warburton and Mr Hendy were reviewing Treasury’s work yesterday, four days before the report’s Monday deadline.

Mr Warburton denied that the review’s independence was compromised by Treasury’s role in sourcing the evidentiary material. He agreed those involved in the review were working “long hours” but denied an overseas trip he is due to make next week had compromised the inquiry.

posted on 31 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Should we be surprised when an adjunct scholar at a supposedly free market US think-tank writes a piece calling for regulatory attacks and litigation against mobile phone users and companies, simply because the author finds mobile phone use annoying?

This is what the AEI’s Jagdish Bhagwati proposes in an article in the FT. Bhagwati compares mobile phone use to bird flu, suggests mobile phone users are breaching human rights conventions and then turns vindictive, saying:

If providence were just, it would surely affect the brains of the users.

Bhagwati is a long-standing apologist for capital controls, belying his reputation as a defender of free trade and globalisation. He is also clearly neurotic.

posted on 30 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

It is not often you can dismiss a forecast as soon as it’s made, but Nouriel Roubini’s latest bit of doom-mongering is DOA. Nouriel suggests that Australia and New Zealand, among others, are set to experience a disruptive currency and financial crisis:

Runs on currency and liquid local assets may still occur with severe and disruptive effects on currency values, bond markets, equity markets and the housing market.

In the case of Australia and New Zealand, this prospect can be dismissed out of hand (I wouldn’t necessarily make this claim for some of the emerging market economies Nouriel lumps in with Australia and NZ). The best evidence against Roubini’s scenario is the experience of both countries in 2001, when the Australian and NZ dollars fell below 0.5000 and 0.4000 respectively. Not only was there no significant disruption to the domestic economy and financial markets of either country, the boost to competitiveness added to the strength of both economies. Nouriel’s assumption that a falling currency woud lead to a dumping of local currency-denominated assets by foreign investors didn’t play out then, not least because many foreign investors are significantly hedged against currency risk. The Australian and NZ dollars are currently falling in part because their debt markets are outperforming the US. If anything, a cheaper currency makes local asset markets even more attractive to fresh inflows of foreign capital.

In recent months, New Zealand authorities have not only welcomed a falling currency, they have even been actively trying to scare-off foreign investors - hardly the actions of a government worried about a currency crisis. The main risk to the NZ economy has been the domestic policy tightening that had seen the NZD trade weighted index to post-float record highs at the end of last year. An exchange rate driven easing in overall monetary conditions is exactly what NZ needs right now.

Roubini’s forecast in relation to Australia and NZ is also difficult to square with his bearishness on the US dollar. According to Nouriel:

U.S. policymakers - both at Treasury and even some, but not all, at the Fed - live in this LaLa Land dream that the U.S. current account deficits and fiscal deficits do not matter and that the U.S. external deficit is all caused by a global savings glut or is actually a “capital account surplus” as it allegedly represents the foreigners’ desire to hold U.S. assets. They - and financial markets and investors - may soon wake up from this unreal dream and face a nightmare where the U.S. looks like Iceland more than they have ever fathomed.

Roubini would have us believe that both the US dollar and the dollar bloc peripheral currencies are at risk, yet this would imply that the AUD-USD and NZD-USD exchange rates should remain relatively stable. It is even harder to envisage an Australian and NZ currency or financial crisis, when the most important exchange rate, that with the US, is largely stable.

Nouriel is the one living in LaLa Land.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

While Peter Costello waits on the results of his international tax beauty contest, Andrew Ball in the FT (via The Australian) notes a recent paper by Eijffinger and Geraats, which:

found that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Swedish Riksbank and the Bank of England were the most transparent central banks. Next came the Bank of Canada, the European Central Bank and the Fed. Bringing up the rear were the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Japan and the Swiss National Bank.

The paper notes the RBA’s many shortcomings:

Although the Reserve Bank of Australia has adopted inflation targeting, it gets one of the lowest transparency scores (8, increasing to 9 in 2002) in our sample. Although the RBA gets the maximum score on political transparency, its openness on other aspects is much less. Economic transparency falls short because it does not publish quarterly data on capacity utilization and only provides rough short term forecasts for inflation (quarterly) and output (semiannually) without numerical details about the medium term. In addition, there was no explicit policy model until October 2001. Procedural transparency is low as the RBA does not release minutes and voting records. There is also scope for greater policy transparency because of the lack of an explicit policy inclination and a prompt explanation of each policy decision. Regarding operational transparency, the RBA provides neither a discussion of past forecast errors, nor an evaluation of the policy outcome. The Reserve Bank of Australia shows that inflation targeting by no means guarantees transparency in all respects.

The RBA’s published policy model (updated late last year) still carries the formal disclaimer that it does not represent the views of the RBA, so it is questionable whether it qualifies as an explicit policy model.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Economist (or more specifically, Lexington) is insufficiently left-wing for Brad Setser:

Lexington could not find any public intellectuals (or ideas) from the center, the center-left or the left worthy of mention…I would say that the interesting policy debate on globalization currently is found on the left, not the right…The left takes seriously idea that the US needs to find ways to share the benefits of globalization more broadly and address growing concerns about economic insecurity and income volatility.

These are more homilies than serious ideas, but the notion that this burden necessarily falls on the United States goes to the heart of Brad’s misdiagnosis of issues such as global imbalances. Whatever institutional short-comings might be found in the US and other Anglo-American countries, it is the rest of the world, not the US, that needs to get its house in order.

posted on 29 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

From The Australian:

According to a report commissioned by the Property Council of Australia, government charges associated with a typical house and land package had risen an average of $77,000 since 2000.

In southeast Queensland’s Redlands Shire those charges had soared 583 per cent in five years to $135,799, while government charges on a house and land package in Adelaide rocketed 331 per cent to $53,003.

But the problem was most pronounced in Sydney’s northwest where 35 per cent - or almost $200,000 - of the price of a new home was eaten up by government charges.

In comparison the cost of the land was only $116,667…

In the five years to 2005 government costs associated with buying a house and land package in northwest Sydney grew 197 per cent to $198,670.

In Melbourne and Canberra those costs grew 146 per cent to $91,135, and 237 per cent to $108,011, respectively.

posted on 28 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

We have previously noted the under-reported business investment boom in Australia, which has taken the investment share of GDP to post-war record highs and which largely explains the widening in Australia’s current account deficit. An even lesser known phenomenon is the fact that Australia is increasingly a net exporter of direct investment capital. Australia is one the biggest suppliers of foreign direct investment capital in the US, a phenomenon noted in this LA Times story from 18 March, reproduced in today’s SMH:

Last year Australian companies sank $US6.1 billion into US real estate, up from $US3.5 billion the previous year…

Real estate isn’t the only area benefiting from Australian investors, who have been enjoying a relatively strong currency and 14 years of growth. Macquarie has also sunk money into major US infrastructure projects, including toll roads in San Diego, Chicago and Washington.

This week, Australia’s Woodside Petroleum unveiled a plan to build a liquefied natural gas terminal off the California coast and BHP Billiton announced similar plans for a floating LNG facility farther north.

Ben Thornley, a New York investment specialist with the Australian Government, said US investment in Australia also was increasing, spurred by the recent completion of a bilateral trade pact.

But he said the US still had the stronger allure, with at least “100 billion Aussie dollars” seeking a home in the US at any given time.

“There’s more money flying out of Australia than going the other direction,” he said.

Some US investors are bypassing Wall Street and heading straight to Australia.

In 2004 Tishman Speyer, the private New York developer, raised $400 million through a property fund it listed on the Australian Stock Exchange.

Rob Speyer said it was much easier to raise capital in Australia than in the US.

posted on 27 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The New Zealand economy contracted by 0.1% in Q4 and averaged 0% growth in the second half of 2005. The data suggest that NZ was heading into recession before 2006 even began. Sadly, these are the sort of macro outcomes to be expected when central bank governors give too much weight to concerns about external imbalances and house prices.

posted on 24 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

James Dorn on the origins of China’s national saving glut:

Of the world’s top 10 biggest trading nations, only China has extensive capital controls. Sure, current-account transactions, or trading in goods and services, are liberalized. But Chinese citizens are barred from investing overseas, interest rates are heavily regulated and domestic stock markets are limited mostly to state-owned enterprises.

China pays a high price for such controls, which distort investment decisions and misallocate capital. Ordinary Chinese suffer too. Denied the right to seek higher returns overseas for their hard-earned savings, they have no choice but to take their chances with poorly regulated domestic investments. And that, in turn, helps explain why China’s savings are so high—and why the much-discussed U.S.-China trade deficit remains intact.

posted on 23 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

New Zealand’s Q4 current account deficit is expected to come in at around 9% of GDP when it’s released tomorrow. The fact that a small open economy like NZ can run such a large deficit should be reassuring. It should also not be surprising. RBA Governor Macfarlane has noted that Singapore ran current account deficits averaging 15% of GDP for a decade, in the context of a much less flexible exchange rate and capital account regime.

Alan Wood notes that ‘the bigger risk is that the RBNZ has raised rates to a level that turns out to be economic overkill,’ an argument we have also made on these pages. The whole point of having a floating exchange rate and open capital account is that monetary policy does not need to concern itself with considerations of external balance or prop up the currency, yet the current account has featured heavily in the RBNZ’s policy discussion of late. As Australia’s experience in the late 1980s and early 1990s demonstrates, external imbalances only become scary when they become a preoccupation of policymakers.

posted on 22 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

Michael Mandel notes some of the problems with proposals for a prediction registry, referencing two of our favourite targets, The Economist magazine and Brad & Nouriel.

posted on 22 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Desmond Lachman continues to trash the AEI’s free market credentials:

If ever over the past sixty years the global economy needed an IMF to effectively discharge its original mandate of helping to safeguard the international exchange system, it has to be now at a time of such large and disturbing global economic imbalances.

There was a time when conservative think-tanks criticised the IMF as a redundant institution in the post-Bretton Woods era. The IMF’s former role in helping countries with the balance of payments problems that emerged under fixed exchange rate regimes was no longer needed once the industrialised world moved to a system of floating exchange rates and open capital accounts. Problems have remained in emerging market economies with fixed exchange rate regimes, but even there, the IMF has played a less than constructive role, as Lachman himself notes. Indeed, reserve asset accumulation on the part of East Asian central banks is partly driven by their view that IMF intervention in the East Asian financial crisis of 1997-98 was a failure.

The argument for doing away with the IMF is compelling, yet growing global ‘imbalances’ have many people arguing for a revival of Bretton Woods era institutions. This is ironic, since it was only under the Bretton Woods system that global imbalances were a serious problem. It is even more ironic that these calls now come from conservative think-tanks. It demonstrates that even they fail to comprehend the free market case for taking a benign view of global imbalances.

Lachman’s argument that global imbalances promote protectionism is quite ridiculous. It is in fact those who fret about global imbalances who are doing the most to promote protectionist sentiment, by promoting the view that these imbalances are somehow a problem requiring a solution.

posted on 21 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ben Bernanke, arguing against the proposition that foreign official reserve asset purchases are a significant determinant of US interest rates:

The performance of Treasuries relative to that of other fixed-income instruments also argues against a dominant influence of foreign official portfolio decisions on long-term rates. If foreign official holdings of Treasuries were the source of the decline in their yields, then we would expect to observe increased spreads between yields on Treasury securities and the returns to other types of debt less favored by foreign official holders. But we have not seen a significant widening of private yield spreads relative to Treasuries—quite the contrary—and, as I noted earlier, yields in other industrial economies have fallen as well, in many cases by more than U.S. yields. A reasonable conclusion is that the accumulation of dollar reserves abroad has influenced U.S. yields, but reserve accumulation abroad is not the only, or even the dominant, explanation for their recent behavior.

posted on 21 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Andy Xie, Morgan Stanley’s house mercantilist, recommends that China resort to central planning to combat higher iron ore prices:

Without government involvement, China’s industries cannot organize to negotiate down the ore price, because the industry is so new and fragmented. Limiting import prices is a good choice, I believe. If the negotiations with the major suppliers do not work out, China’s government should just dictate import prices for the whole year.

This would be a breach of China’s obligations under the WTO, but that doesn’t seem to bother Xie. He goes onto argue:

If China does unilaterally limit import prices, it would not affect supply that much. The ore producers have huge profit margins and have to sell. To whom would they sell without selling to China?

Well everyone apart from China for a start. The desperation of Chinese steel producers is already evident from this story:

Chinese trading companies are surfing a local version of eBay, Alibaba, to scour the world for an increasingly state-controlled resource—iron ore.

Small steel mills, desperate to find iron ore from Brazil, India, Indonesia or New Zealand, can find it on Alibaba, China’s top online business-to-business Web site, which is backed by Yahoo Inc.

Some of the 237 offers available on Friday included photos of a lump of the ore used to make steel.

“We use the Internet as an extension of our services, to let more people know what we have,” said Sun Gongmin, who handles Internet marketing for Beijing Hero Trade Co. “We only started posting iron ore late last year. Before that we’d been pretty successful with rugs.”

“A lot of people have contacted us already, mostly other trading companies helping their clients source a few thousand tonnes here or there. We’re basically just the middlemen.”…

the Shanghai Huozhiyao Import Export Trade Co. offers Indonesian spot ore at $67 (38 pounds) a tonne, illustrated by a photo of a tropical shoreline. Brazilian ore is $69 a tonne.

Spot Indian iron ore in Chinese ports is now valued around $72 to $73 a tonne, traders said. Brazilian ore sold on a term basis is now valued around $67 a tonne, cost and freight.

posted on 18 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

A research paper published under the auspices of the Sydney Futures Exchange seeks to highlight trading opportunities for the global CTA and hedge fund communities in relation to Australia macroeconomic data. The paper examines price volatility in selected futures contracts around various macroeconomic releases.

The results confirm previous studies in both the Australian and US contexts suggesting that the monthly employment numbers have the biggest impact on bond futures prices. In part, this just reflects the volatility in the employment numbers themselves, which are subject to very large standard errors. Outside of consensus employment numbers are thus more common than for other releases.

This still begs the question as to why the market reacts so strongly to a release that is relatively noisy and is widely thought to be a lagging indicator of activity. My own behavioural finance explanation for this is that the monthly employment numbers are one of few indicators that everyone thinks they understand, because they have a fairly unambiguous economic interpretation: employment up, economy up; employment down, economy down. Yet leading indicators of employment widely used in forecasting imply that this information is already in the data, for those who care to look.

posted on 16 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Most analyses of the cost of the war in Iraq fail to take adequate account of the relevant counter-factuals. This paper by academics at the University of Chicago GSB is a notable exception. They conclude that not only are the costs of intervention on a par with the pre-war containment strategy, but that the war will lead to large improvements in the welfare of the Iraqi people.

(via DBRB)

posted on 16 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Back in January, I argued in Business Week that the BoJ would probably relax its previous opposition to an inflation target, in association with the end to quantitative easing and a return to an official interest rate as the BoJ’s main operating instrument. In the event, the BoJ moved a month sooner that I expected. But the BoJ’s ‘New Framework for the Conduct of Monetary Policy’ falls well short of fully fledged inflation targeting.

The new framework defines an inflation rate of 0-2% as desirable over the medium to long term, with the central tendency of BoJ policy board’s view of price stability said to be 1%. As I noted in the article in Business Week, this is consistent with Japan’s long-run average inflation rate. The BoJ says that it ‘will review its basic thinking on price stability, and disclose a level of inflation rate that its Policy Board members currently understand as price stability from a medium to long-term viewpoint, in their conduct of policy.’ This is something that will be ‘reviewed annually’ and the BoJ will ‘conduct monetary policy in the light of such thinking and understanding,’ but otherwise there is no explicit link between inflation outcomes and monetary policy. The inflation target thus does not limit the BoJ’s policy discretion in any way. While announcing an inflation rate deemed consistent with price stability might help in anchoring long-term inflation expectations, it will do little to condition expectations for the near term path of inflation or interest rates. The BoJ’s experience with the zero bound and deflation shows that expectations management is essential to the effective conduct of monetary policy. The BoJ’s new policy framework is a missed opportunity.

posted on 15 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The FT interviews the (thankfully) retiring editor of sister publication, The Economist:

One of his most embarrassing covers, according to Emmott, was in March 1999, about a subject that should have been simple Economist territory: the price of oil. It had its roots in a lunch with an oil company executive, where everybody started musing that, with the oil price at $10, what would happen if it fell to $5? A cover saying that the world was drowning in oil, and noting the possibility of a fall in the oil price, duly appeared. But before the end of the year the price had more than doubled. “It was most embarrassing,” he says candidly.

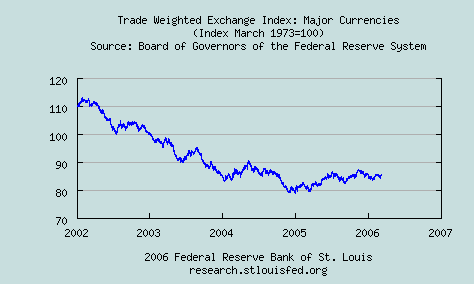

I could suggest a few others. There was also that 2 December 2004 leader on “The disappearing dollar” that said “the [US] dollar could tumble further and further.” The end of 2004 proved to be a major cyclical low for the USD. Contrarian indicators don’t come much better.

posted on 11 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Alan Wood, on the governance of the Future Fund:

Choosing the members of the curiously named board of guardians is up to the responsible ministers - currently Peter Costello and Nick Minchin. (Pursued in senate estimates on the legal standing of the term “guardian” compared with the more familiar term “trustee”, the Government’s Senator George Brandis, a barrister, said the only common law about guardians was in relation to children and the insane.)

The process is much the same as the one that led to the appointment of Rob Gerard to the Reserve Bank board.

Governance issues aside, Wood gets to the heart of why the Future Fund is such a bad idea:

Unfunded public service superannuation liabilities are not a problem.

The size of the liability is not large relative to future budgets and will steadily decline now the Government has closed off most of its defined benefit funds. And there is a strong economic argument for not using budget surpluses to fund these liabilities, put by economist Nicholas Barr from the London School of Economics, an international authority on pension funds. Barr’s basic point is simple but profound - what matters for an ageing population is not how much money it has put away, but availability of goods and services to satisfy its demands. That is, the level of output.

“The point is central,” Barr says. “Pensioners are not interested in money (that is, coloured bits of paper with portraits of national heroes), but in consumption - food, clothing, heating, medical services, seats at football matches, and so on. Money is irrelevant unless the production is there for pensioners to buy.”

Former treasury secretary Ted Evans made the point this way: “Let’s be clear that the ability of future generations, and their governments, to meet the needs of their day will be entirely dependent on the size of the economy they command at the time. Hence the greatest contribution that today’s population can make to the living standards of future generations is to ensure that today’s policies are directed towards maximising future GNP.”

Evans suggested the best way to do this wasn’t through an inter-generational fund like the Future Fund, but by leaving the tax revenue in the hands of taxpayers to spend as they see fit, that is, tax cuts.

Putting surpluses in the Future Fund amounts to increasing tax on this generation of taxpayers. Does increasing the tax burden over the next few years really sound like the best way of increasing GDP in, say, 2020? Hardly.

CIS has a much better idea.

posted on 11 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Yesterday’s announcement of the termination of quantitative easing by the Bank of Japan was pre-empted by Japan’s publicly-funded broadcaster, NHK, by some 45 minutes.

Leaks in relation to BoJ policy are hardly unprecedented. Part of the rationale for the adoption of a two-day meeting format several years ago was to prevent leaks, by holding the policy discussion without a break on the second day. Since yesterday’s meeting ran longer than usual, I’m guessing that there was a break during which the policy discussion was leaked, most likely by the government representatives on the policy board, or their subordinates, rather than the policy board members themselves.

In any event, such leaks are damaging to the credibility of the BoJ and the integrity of Japanese monetary policy and financial markets. In any other country, such indiscretions in relation to official and market sensitive information would be viewed as a serious criminal offence.

posted on 10 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Previously, we highlighted the unprecedented tightening in monetary conditions presided over by RBNZ Governor Bollard. The RBNZ’s March Monetary Policy Statement has now ruled out any easing in official cash rate during 2006.

This can be partly justified by an inflation target breach, but the RBNZ’s discussion of the inflation outlook has recently been dominated by its views on the housing sector and the supposedly ‘unsustainable’ domestic saving-investment and current account imbalance. In the March MPS, Governor Bollard says ‘the other key inflation risk over the next two years remains the housing market. We need to see this market continue to slow, so that consumption moderates and helps to reduce inflation pressures.’

Governor Bollard is implying that causality runs from housing to consumption to overall economic growth to inflation. But if this causal reasoning is wrong, or even if there is bilateral causality between housing and activity more broadly, then the New Zealand economy is in serious trouble. The risk is that by the time the housing market cracks, New Zealand will already be in recession, particularly given the slow transmission from changes in the official cash rate to effective mortgage interest rates in NZ. Indeed, the yield curve inversion driven by RBNZ tightening is even facilitating longer-term fixed rate borrowing, while encouraging capital inflow that makes the current account deficit even worse.

Just like Australia in the early 1990s, the authorities will probably argue that any subsequent recession was necessary to correct these imbalances, substantiating their view about their ‘unsustainability.’ The real lesson from Australia’s experience in the late 1980s and early 1990s is that the monetary authority has no business targeting private saving-investment and current account imbalances or the housing market.

posted on 09 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Chris Masse still doesn’t get it.’ Chris Masse’s 2005 Prediction Market Awards…in 2006. More prediction market links than you can poke a stick at.

posted on 08 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A reader has pointed me in the direction of this speech by the BoE MPC’s Stephen Nickell, which is a thorough de-bunking of the myths in relation to the role of housing and household debt in the UK economy. This piece is remarkable because of its very close fit with the arguments I have been running on the same issues in the Australian context. Nickell summarises his argument as follows:

there has not been a spending boom, the non-spending boom was not credit-fuelled and there has probably not been a house price bubble…what we have seen is first, the average quarterly growth rate of real consumption over the period 2000-2003 has been almost exactly equal to the average growth rate over the last twenty five years, so there was no consumption boom. Second, from 1998 to 2003 the proportion of their post-tax income which has been consumed by households has been stable, despite the fact that mortgage equity withdrawal plus unsecured credit has grown from 2 per cent of post-tax income to nearly 10 per cent of post-tax income over the same period. Third, these two apparently inconsistent facts are reconciled by the fact that since 1998, the increasing rate of accumulation of debt by households has been closely matched by the increasing rate of accumulation of financial assets. Furthermore, this is not an accident. There are good reasons why aggregate secured debt accumulation and aggregate financial asset accumulation might be related, particularly in a period of rapidly rising house prices. Finally, therefore, there is no strong relationship between aggregate consumption growth and aggregate debt accumulation.

Nickell also presents an inventory of busted house price predictions for the UK. The point of this is not to make fun of other people’s failed forecasts (as I am sometimes accused of doing). As Nickell notes, the serious point is that:

commentators (either implicitly or explicitly) disagreed significantly on the long-run equilibrium level of house prices, on where house prices were heading and on the extent to which there was a misalignment or bubble.

In other words, the ‘bubble’ identification problem is so serious as to render the notion of a ‘bubble’ useless as a framework for analysis.

posted on 07 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Warren Buffett, on the high price of his doomsday cultism:

My views on America’s long-term problem in respect to trade imbalances, which I have laid out in previous reports, remain unchanged. My conviction, however, cost Berkshire $955 million pre-tax in 2005.

Buffett is seeking supposedly less costly ways of shorting the US dollar, via apparently unhedged acquisitions of foreign equity capital:

We reduced our direct position in currencies somewhat during 2005. We partially offset this

change, however, by purchasing equities whose prices are denominated in a variety of foreign currencies and that earn a large part of their profits internationally. Charlie and I prefer this method of acquiring nondollar exposure. That’s largely because of changes in interest rates: As U.S. rates have risen relative to those of the rest of the world, holding most foreign currencies now involves a significant negative “carry.” The carry aspect of our direct currency position indeed cost us money in 2005 and is likely to do so again in 2006. In contrast, the ownership of foreign equities is likely, over time, to create a positive carry – perhaps a substantial one.

...and turning equity bets into currency plays.

posted on 06 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Lonely Planet makes its readers feel good about air travel:

the founders of the Rough Guides and the Lonely Planet books, troubled that they have helped spread a casual attitude to air travel that could trigger devastating climate change, are uniting to urge tourists to fly less…

From next month warnings will appear in all new editions of their guides about the impact of flying on global warming alongside alternative ways of reaching certain destinations.

In fact, aircraft contrails may contribute to ‘global dimming,’ thought to be a significant offset to global warming.

posted on 06 March 2006 by skirchner in Culture & Society

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Governor Macfarlane, interviewed in the WSJ:

“I have been in so many meetings, from the late ‘90s onwards, where the participants at the meeting identified the U.S. current account as a serious imbalance that had to be remedied, and that if it wasn’t remedied, the U.S. dollar would go into some sort of free fall and people would stop buying U.S. assets,” he wearily responds. “Clearly, it wasn’t happening. Just as it didn’t happen in Australia.”

posted on 04 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Yesterday’s speech by RBA head of economic analysis Tony Richards included this chart of the various series for Australian house prices. Looking at the level rather than the growth rate of house prices drives home the point that national house prices have been holding their own (although as previous posts have stressed, this conceals important differences between the capital cities).

Needless to say, this is a very different outcome to the doomsday scenarios that were floated not very long ago, which promised national economic ruin on the back of a collapse in house prices (scenarios that are still getting a run in the US context). While the Q4 national accounts were painted as soft on the back of the headline numbers, real household consumption expenditure rose nearly 3% y/y, gross national expenditure rose 4.4% y/y and real gross domestic income rose a stunning 5.2% y/y.

posted on 03 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(6) Comments | Permalink | Main

The 10th anniversary of John Howard’s ascent to the Prime Ministership has not surprisingly seen increased scrutiny of his Deputy, Peter Costello. In part, Costello has drawn this attention to himself, with the announcement of his international tax beauty contest, as well as a recent foray outside his portfolio responsibilities. The punditocracy was unimpressed with both efforts. His speech on citizenship has drawn this response from Greg Sheridan (or at least the sub-editor’s paraphrase):

This shallow, lazy, lucky and opportunistic Treasurer does not deserve to run the country.

On tax, Sinclair Davidson notes:

Apart from some tinkering at the margins, he has done nothing…The top marginal tax rate of 47 per cent has remained unchanged since Paul Keating was treasurer…By calling for a review of the basic facts of the tax system, Costello has shown himself to be years out of date and uninformed. Costello has relied on three arguments to stymie tax reform. First, that Australian tax rates aren’t that high; second, that the tax take is small; and third, that tax reform would only benefit a small number of Australians. Each of these arguments is false.

Alan Wood, by contrast, attempts this rather lame defence of Costello:

this time Australia has avoided the boom’s inflationary consequences, and “there are grounds for optimism it can avoid a subsequent bust”.

If we do, it will be because of the better economic policy framework Costello has played an important role in putting in place.

Peter Costello has cited ‘Reserve Bank independence’ as one of his greatest achievements as Treasurer. The August 1996 exchange of letters between the Treasurer and RBA Governor was in fact a mere codification of existing practice. In 1996, the RBA was already doing what the Treasurer now claims credit for. This fell well short of the comprehensive statutory reform of central banking institutions seen in other countries during the 1990s. Along with the US Fed, this has left Australia with one of the most antiquated frameworks for monetary policy governance among the major industrialised countries.

posted on 02 March 2006 by skirchner in Politics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

BlogAds is conducting a survey of political blog readers. BlogAds will break-out the results obtained from this blog and pass them on to me (make sure you mention Institutional Economics in question 23). If the sample is large enough, I will post the results, which will give you a better picture of your fellow Institutional Economics readers.

You might wonder why this blog is being included in the survey, even though it is not mainly concerned with politics. This is due to the fact that I classified the blog as ‘libertarian’ when I signed-up for BlogAds. While my own politics should be fairly obvious to regular readers, it has never been my intention to run an overtly political blog. The most successful blogs in terms of traffic are strongly partisan, but these sites serve mainly to confirm rather than challenge readers’ views. I have always aimed to appeal to a more diverse readership and I’m hoping this is reflected in the survey results.

posted on 01 March 2006 by skirchner in Misc

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

I would have thought the headline for this story goes without saying:

‘Underground economy baffles Tax Office’

The Tax Office told the Auditor-General it was impossible to assess the size of the cash economy because conclusions would be too imprecise, too costly and the burden on taxpayers would be too intrusive.

“We don’t attempt to estimate it because of the time and cost involved,” a spokeswoman for the Tax Office told the Herald yesterday.

The ATO did, however, find time for this:

The Australian National Audit Office has revealed in its cash economy report that tax investigators contacted more than 50 pole dancing clubs “with a sample receiving unannounced visits”.

Tough job, but someone’s got to do it.

posted on 01 March 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

|