|

The New Yorker on the tragedy that is Paul Krugman:

When the Times approached him about writing a column, he was torn. “His friends said, ‘This is a waste of your time,’ ” Wells says. “We economists thought that we were doing substantive work and the rest of the world was dross.” Krugman cared about his academic reputation more than anything else. If he started writing for a newspaper, would his colleagues think he’d become a pseudo-economist, a former economist, a vapid policy entrepreneur like Lester Thurow?

The rest is history.

posted on 23 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics

(4) Comments | Permalink

RBA Governor Stevens’ appearance before the House Economics Committee on Friday included this exchange with the federal member for Mayo:

Mr BRIGGS—Just on a slightly different track: On 2 November last year there was an article on the Lateline Business program about suggestions that the Reserve Bank executive selectively leaks the likely outcome of the board meeting prior to the board meeting. I guess the presenter summarised it best:

Certainly, there’s disquiet among market economists that the Reserve Bank is selectively briefing certain journalists in the lead-up to rate decisions. Many argue the practice undermines the board process.

I am just interested—did you see the report, and do you have a comment?

Mr Stevens—I did see the report. Apparently there were not too many selective leaks in February, because everybody was surprised, so I am not sure what to make of all this.

Mr BRIGGS—So, you—

Mr Stevens—No, people do not leak the outcome. For a start, the staff do not take calls from the media after the relevant internal meetings where we have come to the view of what we are going to recommend. That is usually on the Thursday morning; the papers go that night. Secondly, we cannot be certain that the board will do what we recommend. It is a board of nine people, and I can assure you they are all of independent mind. People do not leak that information; in my experience the Reserve Bank never has leaked and, if I can help it, it never will.

Stevens is probably correct to argue that the outcome of the Board meeting has never been leaked outright, but that was not what the Lateline Business story was about. The issue raised was whether the RBA backgrounded journalists to the point where they were much better informed about the RBA’s policy bias and therefore better able to call the likely outcome of the Board meeting.

There is evidence on the public record for the view that the RBA has engaged in this practice. In a profile of former Governor Ian Macfarlane published in the AFR Magazine in 2001, a former RBA official is quoted as follows:

The Bank uses newspapers to manage expectations. It’s a game the Bank manages very well. Senior people talk to a small handful of the economics writers from the major papers on a strictly non-attributable basis. I think it’s right to do this from the bank’s point of view, but not necessarily from a public policy view: accountability and a critical press are very important in this system.

That last sentence is the key issue in a nutshell. My sense is that the RBA has now been subjected to sufficient heat over the issue that we won’t see another episode of this in future. The test for the RBA will be whether there is a future recurrence of market speculation about RBA media backgrounding, despite the Governor’s denial.

posted on 20 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(2) Comments | Permalink

Using Freedom of Information legislation, I have obtained a copy of a speech given by Patrick Colmer, Executive Director of the Foreign Investment Review Board, to the Australian-China Investment Forum on 24 September last year. The background to the speech and the FOI process are discussed in an op-ed in today’s Australian.

posted on 19 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Foreign Investment

(0) Comments | Permalink

RBA Assistant Governor Phil Lowe highlights an important change in the RBA’s technical forecasting assumptions:

For some years, it had been our practice to produce forecasts assuming that the cash rate remained unchanged throughout the forecast horizon. This approach had the obvious advantage of simplicity, but when the cash rate is a long way from its normal level, it is not particularly realistic.

So, in August last year we changed our approach. Since then, we have prepared our forecasts on the technical assumption that the cash rate returns towards a more normal setting over time. Our overall objective here is to provide the community with a general sense of how we think the economy is likely to evolve over the next few years and to do this we need to make realistic assumptions. Broadly speaking, the paths the staff have used have been similar to those implied by market interest rates at the time the forecasts were prepared. It is important to stress that this neither implies a commitment by the Board to the particular path used nor an endorsement by the Bank of the market pricing.

This is a welcome change. It makes more sense for an inflation targeting central bank to forecast its own policy rate or to incorporate a market forecast for the policy rate and then base the inflation forecast on this projection. This makes it more explicit that inflation outcomes are not exogenous under an inflation targeting regime.

There was also this endorsement of the macroeconomic benefits of increased labour market flexibility:

The good news is that this flexibility in employment relationships worked in limiting job losses in the economy. This has had obvious social benefits as well as supporting overall confidence in the community. Without this flexibility, it is likely that the outcomes would not have been as favourable.

posted on 18 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(2) Comments | Permalink

This Friday, iPredict launches a host of new contracts with full market-maker liquidity, including a contract on the Australian federal election date and the outcome of the March RBA Board meeting.

posted on 17 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

In an attempt to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat in his wager with Rory Robertson, Steve Keen seeks to lead a lemming-like march of housing doomers up the slopes of Mt. Kosciuszko:

rather than accept the victory of his more bullish opponent, it appears the professor is trying to muster the biggest gathering of market bears in Australian economic history. He has already coined the event ‘‘Walking Against Australia’s Property Mania.’’

Keen will start his 224-kilometre walk from Parliament House in Canberra on April 15, and aside from a documentary crew, his girlfriend and a masseuse, he hopes to be accompanied by some of the 3000-odd members of his Debtwatch blog.

The other side of the bet is unimpressed:

“Betting the house on an economist’s forecast typically is not a smart move. Unfortunately, Dr Keen recklessly encouraged everyday Australians to sell their homes at what turned out to be the peak of the global financial crisis, and the trough in local house prices,” Rory Robertson responded.

“That’s why he’s getting set to walk from Canberra to Mt Kosciuszko wearing a t-shirt saying, ‘I was hopelessly wrong on house prices. Ask me how!’”

posted on 16 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(4) Comments | Permalink

The February Westpac-Melbourne Institute Consumer Sentiment survey finds respondents expecting increases in mortgage interest rates in excess of 100 bp over the next 12 months. While this is somewhat in excess of the tightening in official interest rates recently priced into the inter-bank futures strip, it is not necessarily inconsistent with market pricing. Consumers are by now well aware that the official cash rate is not the only determinant of mortgage interest rates and that there is a trade-off between changes in mortgage interest rates and the official cash rate.

Treasurer Wayne Swan continues to maintain that there is ‘no excuse’ for interest rate movements in excess of movements in the official cash rate. If lenders were to have followed this advice in the past, then none of the benefits of lower funding costs from mortgage securitisation would have been passed on to borrowers before the onset of the credit crisis. Moreover, any future improvement in capital market conditions could not be passed on to consumers, but would instead be hoarded by lenders with the Treasurer’s implicit blessing.

posted on 11 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(3) Comments | Permalink

Today I attended the RBA’s 50th anniversary symposium. The proceedings were not for attribution, but the papers have been published on the RBA’s web site. The session on supply-side issues was a particularly welcome contribution to an area too often neglected by central banks, but one that is inescapably linked to the conduct of monetary policy.

posted on 09 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

The RBA’s decision to leave the OCR unchanged at its February Board meeting is the subject of a lengthy discussion by Adrian Rollins in yesterday’s AFR. The discussion centres on whether the surprise decision was a failure by the market to interpret the signals being sent by the RBA, or whether it was a failure on the part of the RBA to appropriately condition market expectations. This is a joint problem, but one made worse because the RBA is not very good at communicating in a consistent, systematic and structured way.

This is an issue that is more serious than just wrong-footing the market over the outcome of a given Board meeting. Expectations for the future real official cash rate are critical to the transmission of monetary policy and are probably more important to the stance of policy than the actual cash rate. Changes in these expectations can even substitute for changes in the actual policy rate. Poor communication can lead to the effective stance of policy being easier or tighter than the Bank intends, requiring a more activist approach to changes in the OCR than would otherwise be necessary.

For example, it was not unusual for the market to periodically price in a new easing cycle during the 2002-2008 tightening episode. This de facto easing in policy contributed to inflation getting out of control and increased the amount of tightening ultimately required. It is thus very much in the RBA’s interests to ensure that market expectations align with its views.

posted on 05 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(4) Comments | Permalink

The PWC/CSFI Survey of Bank Risk, aka Banking Banana Skins 2010, finds political interference is the number one risk facing the banking industry:

Having bailed the banks out, governments are pushing them to keep lending through the recession, against their better judgment. A director at a large UK bank said that “political meddling in the financial sector is almost universally contradictory and negative. One can’t lend more to support the economy and build up capital bases at the same time”. A credit analyst at a large Japanese bank said that “political interference in both banking and regulation is likely to lead to a mis-allocation of resources, which will probably increase, not decrease, the risk profile of the system”.

In 2005 and 2006, ‘too much regulation’ topped the list of concerns and is still the main concern in the Asia-Pacific region.

Here is another banking banana skin.

posted on 03 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink

The RBA has surprised the punditocracy by leaving the official cash rate unchanged, although financial markets had not fully priced a tightening. The RBA’s decision is consistent with comments made by Deputy Governor Ric Battellino late last year noting that credit conditions had tightened by 100 basis points relative to changes in the official cash rate over the last two years. He also noted that the tightening in lending margins had largely been in the area of business lending, not housing.

Today’s decision puts the bank-bashing by the government and others into proper perspective. The RBA discounts lending margins in its setting of the official cash rate. There are those who persist in believing that there is an interest rate free lunch to be had, if only the banking sector could be made more competitive. Today’s decision shows that monetary policy is so carefully calibrated to prevailing credit conditions that any exogenous easing through increased bank competition would be quickly taken back via the official cash rate. The RBA said so explicitly at the time of its August 2006 interest rate decision:

Compression of lending margins over recent years has contributed to a lowering of borrowing costs relative to the cash rate. This has meant that although the cash rate has recently been slightly above its average for the low-inflation period since 1993, interest rates paid by borrowers have remained below average.

Even Peter Martin is giving Westpac some love, so the message must be slowly sinking in.

posted on 02 February 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(1) Comments | Permalink

Financial market economists are unanimous in expecting a 25 bp tightening from the RBA at Tuesday’s Board meeting, according to a Reuters poll taken today. February inter-bank futures are giving a 69% probability to a 25 bp tightening, while iPredict has an implied probability of 87%. Markets seem to be underpricing a tightening relative to the punditocracy, perhaps reflecting the same concerns driving weakness in equity markets.

posted on 29 January 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(2) Comments | Permalink

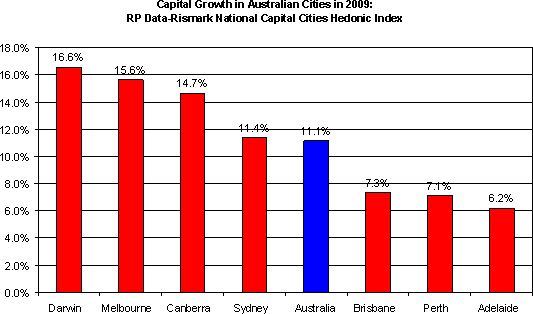

The RP Data-Rismark national capital city hedonic home price index for December shows a modest fall of 0.3% for the month, but up 2.1% for the quarter and 11.1% for the calendar year. This follows modest declines of 2-3% in 2008, which was the worst performance in history on this measure.

posted on 29 January 2010 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(0) Comments | Permalink

From today’s Reserve Bank of New Zealand intra-quarter policy review:

As growth becomes self sustaining, fiscal consolidation would help reduce the work that monetary policy might otherwise need to do.

This is more the RBA’s style (see if you can guess when the RBA said it before clicking here):

The purpose of my answer was to explain why it was wrong to claim that rises in interest rates were due to the stance of fiscal policy.

My answer in no way constituted an attack on the Government’s fiscal policy.

Governor Macfarlane was right to argue that fiscal policy was then irrelevant to inflation and interest rates. But more recently, Governor Stevens has argued that fiscal stimulus has supported economic activity and that there is a trade-off between monetary and fiscal stimulus. Just don’t expect him to spell out the implications of that logic in a policy announcement as candid as that from the RBNZ.

posted on 28 January 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

Fama and French discuss the relative merits of TIPS versus cash as inflation hedges. Cash is an effective inflation hedge because short-term interest rates offer compensation for actual and expected inflation, with very low risk. As French notes:

Because the one-month T-bill rate changes to accommodate changes in expected inflation, unexpected inflation does not have the compounding effect that it has with longer-term bonds.

Of course, this assumes that short-term interest rates remain market-determined rather than set by regulation.

posted on 27 January 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink

Page 35 of 111 pages ‹ First < 33 34 35 36 37 > Last ›

|