|

Joseph Epstein on the disintermediation of print media:

About our newspapers as they now stand, little more can be said in their favor than that they do not require batteries to operate, you can swat flies with them, and they can still be used to wrap fish.

I buy one newspaper a week, but since that is only for the TV guide, it doesn’t really count. I couldn’t even be said to read the on-line versions. So where do all those links come from, you might ask? The answer is Google News Alerts.

posted on 11 January 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

• Saul Eslake’s five-year outlook.

• Some predictions for prediction markets.

• Barry Ritholtz updates the gold bugs’ favourite Rorschach tests.

• David Smith on the dovish UK Shadow Monetary Policy Committee.

• Former Treasury Secretary John Stone on the politicisation of the National Archives.

posted on 10 January 2006 by skirchner in Misc

(1) Comments | Permalink

Alan Reynolds reviews forecasts for 2006, before giving us something real to worry about:

Washington Post columnist Steven Pearlstein just wrote about the “remarkably rosy scenario” of the “economic pundocracy” (though he’s a member). On the same day, Robert Samuelson brushed off all the “sunny predictions” and offered a variation of Pearlstein’s shopping list of things that might go wrong. The dollar might crash, for example, which they almost certainly said last year. Or we might be hit by a comet…

Because inflation is going to be drifting down to 2.4 percent or less for the foreseeable future, there is no “conundrum” in explaining why 10-year bond yields remain low. And there is no plausible rationale for pushing the fed funds rate higher while inflation is heading lower. If the Fed does that, it will be a mistake. Maybe a big mistake.

The federal funds rate was deliberately pushed above the 10-year bond yield in 1969, 1973-74, 1979-81, 1989 and 2000. By no coincidence, the economy was in recession in 1970, 1974-75, 1980-82, 1990 and 2001.

posted on 09 January 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Fortune profiles the views of Roger Ibbotson in its investment review for 2006:

In May 1974, in the depths of the worst bear market since the 1930s, two young men at a University of Chicago conference made a brash prediction: The Dow Jones industrial average, floundering in the 800s at the time, would hit 9,218 at the end of 1998 and get to 10,000 by November 1999.

You probably have a good idea how things turned out: At the end of 1998, the Dow was at 9,181, just 37 points off the forecast. It hit 10,000 in March 1999, seven months early. Those two young men in Chicago in 1974 had made one of the most spectacular market calls in history.

Curiously, the profile then presents the work of Robert Shiller as a challenge to Ibbotson’s approach. Brad DeLong recently reviewed the original forecast that later became the foundation for Shiller’s (2000) Irrational Exuberance:

In 1996 Yale economist Robert Shiller looked around, considered the historical record on the performance of the stock market, and concluded that the American stock market was overvalued. Prices on the broad index of the S&P 500 stood at 29 times the average of the past three decades’ earnings. In the past, whenever price-earnings ratios had been high future long-run stock returns had turned out to be low. On the basis of econometric regression studies carried out by him and by Harvard’s John Campbell, Shiller predicted in 1996 that the S&P 500 would be a bad investment over the next decade. In the decade up to January 2006, he predicted, the real value of the S&P 500 would fall, and even including dividends his estimate of the likely real inflation-adjusted returns to be earned by investors holding the S&P 500 was zero.

The rest, as they say, is now history.

posted on 06 January 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Brad Setser on his macroeconomic hypochondria:

What’s new. I always worry. I just now worry about a (somewhat) new and evolving set of things.

Like the song says, don’t worry, be happy!

Speaking of happy, Mark Mahorney is wishing everyone a Happy New Year. Well, almost everyone:

everyone except the name caller, the perma-bears, commie-lovers…Everyone except all of those people.

posted on 05 January 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Kevin Hassett, drawing on Robert Barro’s work on ‘Rare Events and the Equity Premium,’ asks whether the prospect of a show-down over Iran’s nuclear program might be responsible for low bond yields:

If Barro is right, long-term rates may depend on low- probability geopolitical variables. And the effects may be enormous, perhaps even dwarfing the effects of traditional variables such as the deficit.

Barro clarified this connection in a recent interview: “A small increase in this kind of risk—as an example, due to the Sept. 11th events—leads to a noticeable response in real interest rates. When this probability goes up, the risk-free rate goes down because people put more of a premium on holding a relatively safe asset.”…

there has been a movement that is consistent with the Barro story. Intrade.com offers a futures contract that pays off if the U.S. or Israel bombs Iran between now and the end of March 2007. That probability has soared in recent weeks, and stood at a sobering 31.6 percent on Dec. 30…

Iran, not Iraq, may be the big story of 2006, both politically and economically.

I prefer a monetary policy credibility explanation for low bond yields, but would agree that Iran will loom large this year.

posted on 04 January 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Brad Setser reviews the year that was in ‘Things I Got Wrong in 2005’:

Alas, this list is rather long.

To be fair, this sort of candour is quite admirable and not often seen among pundits.

Don Boudreaux has an extract from a recent interview with Milton Friedman that touched on the subject of global imbalances. RBA Governor Ian Macfarlane made much the same point in a speech earlier this year, which should have received a lot more attention than it did:

the scenario whereby world financial markets react to the US current account deficit by withdrawing funding has disappointed those who thought it would come into play. It may happen yet, but people have been predicting it for a long time and yet it seems no closer. A large part of the reason for this is that investors who want to get out of US dollars have to run up their holdings of another currency – they cannot get out of US dollars into nothing. They have to take the risks involved in holding some other currency, possibly at an historically high exchange rate, and they may well be reluctant to do so.

posted on 31 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

As usual, blogging will be light at best over the Christmas-New Year period. Thanks to IE readers, tipsters and advertisers for their support throughout the year. Hope you had as much fun reading it as I did writing it.

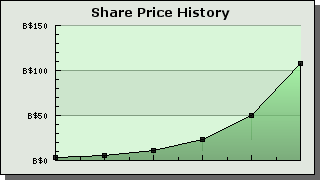

Having spent much the last 12 months rubbishing the notion of ‘bubbles’ in asset prices, I should draw readers’ attention to a bit of asset price inflation in which you are all implicated. Here is the Institutional Economics stock price at Blogshares since April this year:

It’s all due to fundamentals! Back in January for another year defending capitalist acts between consenting adults against fever-swamp Austrians, Roubini-Setser doomsday cultists, the AEI’s resident evils, and Economist leader writers.

posted on 23 December 2005 by skirchner in Misc

(1) Comments | Permalink

The CIS gets behind the idea that the Future Fund should instead be used to endow individual private saving accounts:

A better alternative to the Future Fund would be to hand back the surpluses to the taxpayers who are funding them, and to remit future receipts from the sale of Telstra to the Australian public who notionally own these assets. In this way, the government could enable ordinary people to start saving for their own futures, rather than have the government doing it for them.

The Future Fund is expected to exceed $60 billion by mid-2007. An equal share-out among all permanent residents in Australia (children as well as adults) could at that time provide everyone with their own personal ‘future fund’ (PFF) worth around $3,000. Further dividends from the Government as it disposes of surpluses in the future, together with contributions from individuals themselves, could swiftly raise this to around $5,000 per person.

posted on 21 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Stephen Jen on the lessons of 2005:

I have given up trying to convince the structural USD bears about the benign perspective on global imbalances. After a year-and-a-half of hard marketing, I have come to the realization that investors’ structural views on the USD are deeply entrenched: the bears will always be bears.

posted on 20 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Alan Kohler, referring to Greg Smith’s presentation to the Australian Tax Research Foundation’s Tax Leader’s Forum, highlights the extent to which the increased public saving represented by the federal budget surplus has come at the expense of private saving:

of the $47 billion in underlying cash budget surpluses accumulated since 1996, $39 billion, or 83 per cent, came from taxes collected from super funds.

In other words the Howard Government’s accumulated surpluses are largely just a transfer of private savings to public savings. The taxes collected from super funds haven’t even been spent! ...

Greg Smith says: “Australia is one of the very few countries to tax superannuation funds [on earnings and contributions]. This essentially transfers private to public savings, substantially neutralising the national economic benefits of running a budget surplus.”

That is, the budget surplus is not a result of excellent economic management or government administration, but is simply the forced transfer of wealth from private savings to public. Nothing has been created.

This is what makes the impounding of part of the budget surplus and the proceeds from the sale of Telstra in the Future Fund so inexcusable. The financial assets that will acquired by the Fund should instead be residing in the private retirement accounts of individual working Australians, reducing their future dependence on government.

posted on 17 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

The RBA is willing to pay a high price to keep its deliberations from public scrutiny:

THE Reserve Bank of Australia spent $304,530 on lawyers to block a Freedom of Information request to release details of its board’s deliberations over interest rates.

The RBA hired a team of lawyers from Clayton Utz to keep secret from The Weekend Australian the central bank’s board minutes for the 12 months to March last year.

Files from the Attorney-General’s Department show Clayton Utz’s bill was $275,458 for solicitors’ fees and $29,072 for legal counsel fees for four months to November last year.

The cost is revealed in the Attorney-General’s FOI annual report…

The proceedings before the AAT were effectively brought to an end when the RBA issued a conclusive certificate, which perhaps offers a hint as to the nature of the legal advice they received.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Wayne Swan said the legal bill seemed “an extraordinarily large amount of money”.

“We need more transparency and openness when it comes to Reserve Bank appointments and their deliberations,” Mr Swan said yesterday.

The ALP backed away from reforms to the RBA Act ahead of last year’s federal election. It remains to be seen whether they can put up a meaningful reform proposal before the next one.

posted on 17 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

The increased budget surplus reported in Mid-Year Economic & Fiscal Outlook has seen the usual spate of calls for further tax reform. However, the budget surplus should in no sense be viewed as defining the scope for further reform. Meaningful reform needs to go well beyond a handing back of a portion of the surplus and extend to a complete overhaul of the current system of tax concessions and Commonwealth government spending, particularly the middle class welfare churn, which sees many households paying no net tax. This makes wholesale tax reform readily affordable out of existing government spending programs.

This point is clearly understood by Malcolm Turnbull, who (perhaps not coincidentally) gave a speech on tax reform yesterday coinciding with the Treasurer’s release of the MYEFO. Turnbull draws on President Bush’s Tax Reform Panel to argue for what amounts to a radical re-think of the tax system. Turnbull is even willing to put a flat tax and the abolition of taxes on saving, such as capital gains tax, on the table:

A flat tax is not, of course, truly flat. Flat tax systems impose a single tax on income with the broadest possible definition and with very few deductions. Progressivity, or vertical equity, is maintained by having a tax free threshold which can be adjusted for family size. There is no need whatsoever for a flat tax to be regressive.

The greatest economic benefit claimed for so called flat taxes is that income is taxed only once: either at the business level or at the household (or wage earner) level. This means that income from investments be it interest or capital gains is not taxed in the hands of the recipient, although of course when it is spent it is taxed because it becomes income in the hands of the business or individual who receives it. This reduces the bias against savings and investment which slows capital formation and as a consequence wage growth.

Compare and contrast Treasurer Costello’s most recent speech on tax to the Global Tax Forum, which was essentially arguing for the cartelisation of international taxation and enhancing ‘national tax sovereignty.’ Who would you rather have as Treasurer?

posted on 16 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(5) Comments | Permalink

US Senators make lousy Presidential candidates, but John Fortier argues that Hillary Clinton and John McCain are the exceptions to the rule:

Senators who look in the mirror think they see the next president of the United States. History, however, has shown that the reflection is that of a losing candidate…

Only two sitting senators have ever won the presidency—John F. Kennedy and Warren Harding—and both had short and relatively undistinguished Senate careers. By contrast, consider the success of governors. Not only have four of our last five presidents been governors but incredibly none had even held a real job in Washington before entering the presidency.

Clinton and McCain are currently the highest priced Intrade contracts for securing their party’s nomination. Unfortunately, the market is giving a very low probability to the Hillary-Condi contest favoured by Dick Morris:

Rice is the only figure on the national scene who has the credentials, the credibility, and the charisma to lead the GOP in 2008…a race between these two commanding, but very different, women is a very real possibility - and would inevitably prove one of the most fascinating and important races in American history.

posted on 15 December 2005 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink

It is unfortunate that RBA Governor Macfarlane does not speak in public more often. He has made only seven public presentations this year, including two before the House Economics Committee. What makes Macfarlane so interesting is his deep understanding of the importance of institutions and his broad historical perspective. Both were in evidence in his speech to the Australian Business Economists, in which he highlighted the importance of institutional change in contributing to the resilience of the Australian economy in recent years, even going so far as to suggest that Australia served as a model in this regard (for Chile anyway!)

Being something of an economic history buff, Macfarlane produced the following chart, showing the unprecedentedly low level of nominal interest rates among the world’s major economies in recent years. He also produces a table showing that world interest rates have been very low even in real terms.

posted on 13 December 2005 by skirchner in Economics

(3) Comments | Permalink

Page 92 of 111 pages ‹ First < 90 91 92 93 94 > Last ›

|