|

Once every three months, financial markets turn to the RBA’s quarterly Statement on Monetary Policy for guidance on the monetary policy outlook. More often than not, they are disappointed. It’s not hard to see why. The quarterly Statements are scheduled after the Board meeting that follows each quarterly CPI release, so they typically serve as vehicles for the ex post rationalisation of existing policy moves, while studiously avoiding any explicit discussion of the policy outlook. The broad-brush inflation forecasts contained in the Statements have taken on an increasingly endogenous character, being left largely unchanged from one Statement to the next because of intervening policy moves. It is unlikely that the RBA would forecast underlying inflation outside the target range, since this would beg the question as to why policy action had not already been taken to pre-empt it. The Bank would essentially be admitting that it was in the process of making a policy error.

Instead of persisting with the fiction that inflation is an exogenous variable, the RBA should move to formally endogenise its forecasting process to a published projection for the official cash rate that it believes is likely to be consistent with maintaining inflation within the target range. This would help ensure the credibility of its medium-term inflation target, by making it more explicit that inflation is not an exogenous variable under an inflation targeting regime, as well as giving clearer guidance on the monetary policy outlook.

posted on 04 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Stephen Gordon’s recollection of RBA Governor-designate Glenn Stevens:

We both did our MA at the University of Western Ontario during the academic year 1984-85. I’m pretty sure that Glenn Stevens was the best student of our cohort (I think I was second), and I remember him telling me that UWO tried very hard to persuade him to stay on to do a PhD. He thought that it would be a waste of time, since he wasn’t interested in academia. Thinking of the Bank of Canada - where it’s well-nigh impossible to go very far without a doctorate - I asked him if he was worried about limiting his options. He didn’t think he was - and it turns out the he was right.

In his picture, he has much less hair than I remember. But then again, so do I.

Good on you, Glenn; I wish you well from the other side of the world.

Another profile of Glenn Stevens here.

posted on 02 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

More on Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales, from the Atlantic Monthly:

Wales is of a thoughtful cast of mind. He was a frequent contributor to the philosophical “discussion lists” (the first popular online discussion forums) that emerged in the late ’80s as e-mail spread through the humanities. His particular passion was objectivism, the philosophical system developed by Ayn Rand. In 1989, he initiated the Ayn Rand Philosophy Discussion List and served as moderator…

Openness fit not only Wales’s idea of objectivism, with its emphasis on reason and rejection of force, but also his mild personality.

posted on 02 August 2006 by skirchner in Culture & Society

(0) Comments | Permalink

The government’s claim that it can keep the level of interest rates lower than the opposition Labor Party may have been an effective line at the last federal election. The downside is that it makes it harder for the government to then turn around and disassociate itself from interest rate outcomes in the midst of a tightening cycle. In the short-run, interest rate determination has very little to do with anything the government does (within reasonable bounds) and the policy differences between the two major parties are certainly not large enough to have a significant influence on interest rate outcomes.

Interest rates can be expected to cycle around their long-run equilibrium real rate. This long-run real rate is determined by structural factors, such as productivity growth and the real rate of return on capital. We are conditioned to think of higher real interest rates as being bad for economic growth, but this is true only in a narrow cyclical sense. The long-run real rate is determined by the real rate of return on invested capital and we want this rate to be higher, not lower. Countries like Australia and New Zealand have higher interest rates than found in many other industrialised countries in part because their growth prospects are relatively stronger (it is also why they have relatively large current account deficits). High real interest rates and current account deficits are symptomatic of economic strength, not weakness.

The country that has been most successful in keeping interest rates low in recent years has been Japan, which achieved this dubious distinction by saving too much, over-capitalising its economy and trashing the real rate of return on invested capital. Not coincidentally, Japan also runs a current account surplus.

posted on 01 August 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

It doesn’t take much to get Nouriel Roubini excited these days. US Q2 GDP falls short of expectations, and Nouriel starts salivating over the prospect that the cycle might finally validate his years of perverse doom-mongering:

this Q2 GDP report is as bad as it could be. I thus stick with my prediction that, by Q4, the growth rate will be close to zero and by early 2007 the U.S. will be in a recession. Panglossian optimists have been proven wrong again. They’d better start adjusting their wishful-thinking forecasts of H2 growth (still close to a 3% consensus) to a reality of an economy rapidly slipping into an [sic] nasty recession.

Nouriel is nothing if not thorough in his bearishness. If Nouriel is to be believed, not a single asset class or region will be spared:

In 2006 cash is king and all risky assets (equities, EM bonds, currencies and equities, commodities, credit risks and premia) will be battered once the markets finally comes [sic] to the realization that a U.S. recession followed by a serious global slowdown is coming.

Finally the other delusion in the market is that, even if the U.S. were to slow down, the rest of the world (EU, Asia, China, Japan, Emerging Markets) will be able to “decouple” from the U.S. slowdown and keep on growing perkily…quite simply, when the U.S. sneezes the rest of the world gets the cold. The decoupling fairy tale will be proven as wrong as the U.S. soft landing Panglossian fairy tale.

So Nouriel pretty much has all bases covered for anything that might go wrong anywhere in the world for the foreseeable future.

posted on 29 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

The Prime Minister says he has not ‘met a political leader who can stop a cyclone,’ but the government can certainly stop banana imports:

Biosecurity Australia has been considering an application from The Philippines to export bananas to Australia since 2000 and made a draft recommendation two years ago that conditional permission be granted.

The draft produced a storm of protest from growers and a senate inquiry, forcing the Government to send Biosecurity Australia back to the drawing board to prepare a further risk assessment next year.

This week’s CPI shock is a nice case of protectionism coming back to bite the government in the arse.

posted on 29 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Clive Crook on the failure of the Doha Round:

The saddest part is that the process itself is no longer mitigating that problem but compounding it. The World Trade Organization and its precursor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, were designed as a forum in which governments could demonstrate to their electorates that trade liberalization was a win-win game. Rather than convincing voters that lowering their own tariffs is good for them (as it is), the process relied on showing that other countries would lower their tariffs as well. The model was based on an exchange of “concessions”—trade reform as shared sacrifice. It was intellectually dishonest but, undeniably, it worked. In the decades after 1945, the world moved from comprehensively managed trade to a more liberal trading order, with fabulous economic results.

Big exceptions remained—notably agriculture, ever the sticking point—but nobody was complaining. The system was apt to wobble from time to time, as you might expect, because it was based on a lie. But for a good few decades it effectively mobilized export interests against groups demanding protection, and the politics worked.

Progress was slowing even before the Doha Round. But this week the “exchange of concessions” model finally fell in on itself. The WTO process is no longer assisting liberalization. It is blocking it and, worse, legitimizing the failure. The world has settled for less-than-liberal trade. It is a multitrillion-dollar error; a crime, truly, against the world’s poor; and, it seems, a story barely worth reporting.

posted on 29 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Vanguard Australia is presenting a seminar by Dr Burton G. Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, and Chemical Bank Chairman’s Professor of Economics at Princeton University, 17 August at the Westin Hotel, Martin Place, Sydney. The topic for the seminar, not surprisingly given the sponsor, is ‘Why It Pays to Invest in Index Funds.’

You can register here.

posted on 28 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

The New Yorker on Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales:

As an undergraduate, he had read Friedrich Hayek’s 1945 free-market manifesto, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” which argues that a person’s knowledge is by definition partial, and that truth is established only when people pool their wisdom. Wales thought of the essay again in the nineteen-nineties, when he began reading about the open-source movement, a group of programmers who believed that software should be free and distributed in such a way that anyone could modify the code.

posted on 27 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

The 1.6% quarterly and 4% through the year increase in the CPI in the June quarter will be seen cementing the case for an interest rate increase from the RBA next week.

In reality, the headline June quarter inflation number will have little to do with the reason the RBA is likely to raise interest rates. Petrol and fruit prices together contributed one percentage point to the headline increase over the quarter, with a 250% Cyclone Larry-induced increase in banana prices the main culprit in higher fruit prices. Strip out volatile and non-market determined prices and the CPI rose a more subdued 0.6% q/q and 2% y/y.

What is likely to concern the RBA is the firming trend in the various measures of underlying inflation, at a time when its medium-term inflation forecast is already near the top of its 2-3% target range. The continued run of strong activity data, including the probability the unemployment rate will post new near 30 year lows in the months ahead suggests further upside risks to the RBA’s inflation forecast.

What should concern the RBA even more is that its inflation target appears to have lost credibility with the bond market. Yields on inflation-linked Treasury bonds have implied an inflation rate above 3% since December 2005, with the implied 10 year inflation rate having risen steadily from 1.9% back in June 2003 amid the global deflation scare of that year. With the exception of the uncertainties surrounding the introduction of the GST in 2000, this is the first time the implied inflation rate has been above the inflation target range since 1997.

posted on 26 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(3) Comments | Permalink

This year’s RBA conference volume is up in draft form. This year’s conference looked at:

the impact of demographic trends on macroeconomic factors relevant to financial markets, particularly saving and investment, capital flows and asset prices, as well as on the structure and operation of financial markets. The participants also placed considerable focus on policy issues, identifying the nature and extent of possible market imperfections and impediments, and the scope for policy-makers to address these.

Robin Brooks’ paper on Demographic Change and Asset Prices:

finds little evidence to suggest that financial markets will suffer abrupt declines when the baby boomers retire. In fact, in countries where stock market participation is greatest, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US, evidence suggests that real financial asset prices may continue to rise as populations age, consistent with survey evidence that households continue to accumulate financial wealth well into old age and do little to run down their savings in retirement.

posted on 25 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Kate Legge on John Hewson (Weekend Australian magazine, no link):

[his] absence from politics for more than a decade has not lessened his passion to prune and fertilise our national landscape.

posted on 22 July 2006 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Even the cyclical US dollar bears are capitulating:

We have argued for more than two years now that the dollar is structurally sound, and the market’s fixation on using the dollar as the key tool of C/A adjustment is a fundamentally flawed notion, reflecting a lack of understanding of the effects of globalization. To us, outsized global imbalances are a logical consequence of globalization of the goods and the assets markets. We won’t repeat the details of our thesis on the dollar, but only stress that our call this year for the dollar to correct has been based purely on cyclical considerations. We are not sympathetic to the popular notion that the dollar ‘must’ correct sharply or crash, and that 2005 was a bear market rally in a secular dollar decline. This is why the changing cyclical outlook of the US and the global economies has such a major impact on the trajectory of the dollar…

As US inflation trends higher and global interest rates continue to rise, the dollar will be supported. The nominal short-term cash premium of the USD has reached 2.7%, and is still rising. We have long warned about the impact of the upside surprise in US inflation on the dollar and how it could alter our currency forecasts. We now believe that the cyclical dollar correction we had expected to take place in 2H this year may be further postponed to 4Q this year.

A recent IMF Working Paper sheds light on the structural underpinnings of the USD:

the presence of negative dollar risk premiums (i.e. expectations of a dollar depreciation net of interest rate effects) amid record capital inflows could suggest that investors may favor U.S. assets for structural reasons. One possible explanation could be that the Asian crisis created a large pool of savings searching for relatively riskless investment opportunities, which were provided by deep, liquid, and innovative U.S. financial markets with robust investor protection. Moreover, the continued attractiveness of U.S. financial markets to European investors suggests that they offer a large array of assets, with different risk/return characteristics, that facilitate the structuring of diversified investment portfolios. Looking forward, this suggests that the allocative efficiency of U.S. financial markets could mitigate risks of a disorderly unwinding of global current account imbalances.

posted on 22 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

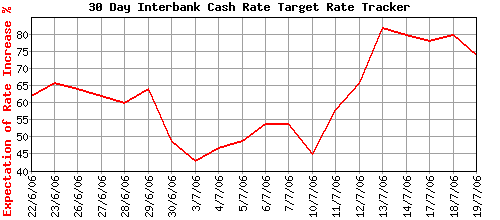

The implied probability of a 25 bp tightening in the official cash rate to 6.00% at the RBA’s August meeting has firmed in the wake of last week’s strong June employment report, peaking at just over 80%, based on the August 30-day interbank futures contract.

posted on 20 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Kevin Hassett extrapolates from historical experience:

A 37 percent move up from $78, pushing even past $100, is certainly possible given past oil-price responses to war in the Middle East. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, oil prices increased by exactly that percentage during the course of the fighting…

Given that there are many signs the U.S. economy has already been slowing, such a surge in oil prices might well be enough to push the economy into a recession.

There is significant historical precedent. The 1956 war in Egypt shut the Suez Canal to oil tankers. Oil producers cut output by 1.7 million barrels a day, roughly a 10 percent decrease in world oil production. Prices surged, and by August 1957, we were formally in a recession.

The outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 caused world oil production to drop 7.2 percent. By July 1981, there was a recession. Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, and the same pattern held.

With that likelihood, expect the normal “flight-to-safety” assets to rally if full-scale war erupts. Gold prices would head way up, interest rates on government securities way down. During the 1982 Lebanon War, the 10-year Treasury bill rate dropped 12 percent in the 11 weeks from just before war began in early June to Aug. 24, 1982, the day after the PLO agreed to withdraw its forces.

The stock market would also take a big hit, history shows. During the course of the Suez Crisis in 1956, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index dropped 5 percent.

posted on 18 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Page 83 of 111 pages ‹ First < 81 82 83 84 85 > Last ›

|