A Random Walk Down Martin Place

Vanguard Australia is presenting a seminar by Dr Burton G. Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, and Chemical Bank Chairman’s Professor of Economics at Princeton University, 17 August at the Westin Hotel, Martin Place, Sydney. The topic for the seminar, not surprisingly given the sponsor, is ‘Why It Pays to Invest in Index Funds.’

You can register here.

posted on 28 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Hayekian Origins of Wikipedia

The New Yorker on Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales:

As an undergraduate, he had read Friedrich Hayek’s 1945 free-market manifesto, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” which argues that a person’s knowledge is by definition partial, and that truth is established only when people pool their wisdom. Wales thought of the essay again in the nineteen-nineties, when he began reading about the open-source movement, a group of programmers who believed that software should be free and distributed in such a way that anyone could modify the code.

posted on 27 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Yes, We Have No Bananas: Anatomy of an Inflation Shock

The 1.6% quarterly and 4% through the year increase in the CPI in the June quarter will be seen cementing the case for an interest rate increase from the RBA next week.

In reality, the headline June quarter inflation number will have little to do with the reason the RBA is likely to raise interest rates. Petrol and fruit prices together contributed one percentage point to the headline increase over the quarter, with a 250% Cyclone Larry-induced increase in banana prices the main culprit in higher fruit prices. Strip out volatile and non-market determined prices and the CPI rose a more subdued 0.6% q/q and 2% y/y.

What is likely to concern the RBA is the firming trend in the various measures of underlying inflation, at a time when its medium-term inflation forecast is already near the top of its 2-3% target range. The continued run of strong activity data, including the probability the unemployment rate will post new near 30 year lows in the months ahead suggests further upside risks to the RBA’s inflation forecast.

What should concern the RBA even more is that its inflation target appears to have lost credibility with the bond market. Yields on inflation-linked Treasury bonds have implied an inflation rate above 3% since December 2005, with the implied 10 year inflation rate having risen steadily from 1.9% back in June 2003 amid the global deflation scare of that year. With the exception of the uncertainties surrounding the introduction of the GST in 2000, this is the first time the implied inflation rate has been above the inflation target range since 1997.

posted on 26 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

Demographic Change and Asset Prices

This year’s RBA conference volume is up in draft form. This year’s conference looked at:

the impact of demographic trends on macroeconomic factors relevant to financial markets, particularly saving and investment, capital flows and asset prices, as well as on the structure and operation of financial markets. The participants also placed considerable focus on policy issues, identifying the nature and extent of possible market imperfections and impediments, and the scope for policy-makers to address these.

Robin Brooks’ paper on Demographic Change and Asset Prices:

finds little evidence to suggest that financial markets will suffer abrupt declines when the baby boomers retire. In fact, in countries where stock market participation is greatest, including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US, evidence suggests that real financial asset prices may continue to rise as populations age, consistent with survey evidence that households continue to accumulate financial wealth well into old age and do little to run down their savings in retirement.

posted on 25 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Capitulation of the Cyclical US Dollar Bears: Doomsday Postponed (Again)

Even the cyclical US dollar bears are capitulating:

We have argued for more than two years now that the dollar is structurally sound, and the market’s fixation on using the dollar as the key tool of C/A adjustment is a fundamentally flawed notion, reflecting a lack of understanding of the effects of globalization. To us, outsized global imbalances are a logical consequence of globalization of the goods and the assets markets. We won’t repeat the details of our thesis on the dollar, but only stress that our call this year for the dollar to correct has been based purely on cyclical considerations. We are not sympathetic to the popular notion that the dollar ‘must’ correct sharply or crash, and that 2005 was a bear market rally in a secular dollar decline. This is why the changing cyclical outlook of the US and the global economies has such a major impact on the trajectory of the dollar…

As US inflation trends higher and global interest rates continue to rise, the dollar will be supported. The nominal short-term cash premium of the USD has reached 2.7%, and is still rising. We have long warned about the impact of the upside surprise in US inflation on the dollar and how it could alter our currency forecasts. We now believe that the cyclical dollar correction we had expected to take place in 2H this year may be further postponed to 4Q this year.

A recent IMF Working Paper sheds light on the structural underpinnings of the USD:

the presence of negative dollar risk premiums (i.e. expectations of a dollar depreciation net of interest rate effects) amid record capital inflows could suggest that investors may favor U.S. assets for structural reasons. One possible explanation could be that the Asian crisis created a large pool of savings searching for relatively riskless investment opportunities, which were provided by deep, liquid, and innovative U.S. financial markets with robust investor protection. Moreover, the continued attractiveness of U.S. financial markets to European investors suggests that they offer a large array of assets, with different risk/return characteristics, that facilitate the structuring of diversified investment portfolios. Looking forward, this suggests that the allocative efficiency of U.S. financial markets could mitigate risks of a disorderly unwinding of global current account imbalances.

posted on 22 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

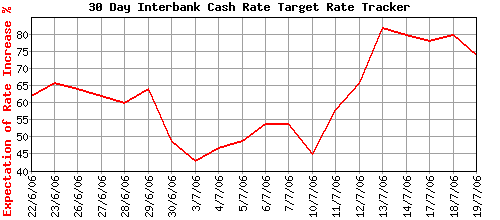

RBA Rate Hike Probabilities

The implied probability of a 25 bp tightening in the official cash rate to 6.00% at the RBA’s August meeting has firmed in the wake of last week’s strong June employment report, peaking at just over 80%, based on the August 30-day interbank futures contract.

posted on 20 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Economic Consequences of War in the Middle East

Kevin Hassett extrapolates from historical experience:

A 37 percent move up from $78, pushing even past $100, is certainly possible given past oil-price responses to war in the Middle East. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, oil prices increased by exactly that percentage during the course of the fighting…

Given that there are many signs the U.S. economy has already been slowing, such a surge in oil prices might well be enough to push the economy into a recession.

There is significant historical precedent. The 1956 war in Egypt shut the Suez Canal to oil tankers. Oil producers cut output by 1.7 million barrels a day, roughly a 10 percent decrease in world oil production. Prices surged, and by August 1957, we were formally in a recession.

The outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 caused world oil production to drop 7.2 percent. By July 1981, there was a recession. Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, and the same pattern held.

With that likelihood, expect the normal “flight-to-safety” assets to rally if full-scale war erupts. Gold prices would head way up, interest rates on government securities way down. During the 1982 Lebanon War, the 10-year Treasury bill rate dropped 12 percent in the 11 weeks from just before war began in early June to Aug. 24, 1982, the day after the PLO agreed to withdraw its forces.

The stock market would also take a big hit, history shows. During the course of the Suez Crisis in 1956, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index dropped 5 percent.

posted on 18 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

In Defence of Bernanke

James Surowiecki defends Ben Bernanke’s commitment to a more open communications style:

acknowledging uncertainty doesn’t play well with the media or the market. Today, the Fed’s actions are subject to constant press scrutiny. And it’s easier to lure audiences by using labels like “hawk” and “dove” than by exploring the subtleties of forecasting an uncertain future. In theory, investors should look past the headlines to the substance, but if the multitudes are treating the headlines as important news it’s hard for any individual investor not to do likewise.

John Taylor argues that recent Fed policy actions accord with his ‘Taylor principle:’

Since the beginning of Mr. Bernanke’s term, the Fed has responded by raising the funds rate by 75 basis points—to 5.25% from 4.5%, which is the neutral rate according to the St. Louis Fed’s version of the “Taylor rule.” This rise appears to be more than the increase in inflation since the start of his term; so, thus far, the Bernanke Fed is following a key principle of monetary success. There is likely to be some more work to do, however. If the inflation rate of personal consumption expenditures (PCE) continues at the 3.3% pace of the past 12 months, then a funds rate of 6.5% will be needed.

Oddly enough, Taylor opposes formal inflation targeting, even though an inflation target is implicit in his Taylor rule.

posted on 13 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

When a Nork Missile Launch is Not a Nork Missile Launch

Can a prediction market fail to predict even the past? One of the more vexed issues for prediction markets is defining the terms of their contracts. Intrade’s North Korean missile launch contract has continued to trade, because the US DoD has not officially confirmed that the missiles left North Korean airspace (12 nautical miles from the coast), as per the terms of the contract. NorCom will only say the missiles landed in the Sea of Japan.

In absence of such confirmation, Intrade will expire the contract at zero, even if more missiles are launched. The price action in the contract thus probably tells us more about the confusion over the terms of the contract and the willingness of the DoD to divulge additional information than it does about the prospects for missile launches. It also provides a nice illustration of the role of asymmetrical information in markets, given the willingness of some to short the contract in the immediate aftermath of the missile launches, with volume exceeding what would be expected from the squaring up of long positions placed in advance of the launches. See the discussion at the TEN Forum (via Chris Masse).

UPDATE (17 July): More on the North Korean missile launch that wasn’t, from Intrade:

Dublin, July 17, 2006: North Korea Missile Test Exchange News Update

The Exchange confirms that it has sought direct confirmation from the US Department of Defense regarding the above contract.

As of today’s date no such confirmation has been received.

As is standard operating procedure to ensure orderly operation and expiry of all markets, the Exchange is and will remain proactive in looking for verifiable settlement related information from the relevant authority.

The Exchange will not use third party non-verifiable confirmations for settlement of any contract.

posted on 10 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Why Glenn Stevens Will Enjoy a Smoother Transition than Ben Bernanke

Ian Macfarlane’s current three year term as RBA Governor ends in September. The SMH profiles his likely successor, Deputy Governor Glenn Stevens:

Your mortgage may soon be in the hands of a guitar-playing amateur pilot from Sylvania Waters.

Glenn Stevens is likely to enjoy a much smoother transition than Ben Bernanke. An incredible amount of nonsense was written about Bernanke as he moved into his role as Fed Chairman and markets are probably still less than fully sold on his inflation-fighting credentials. This is a reflection of the weakness of the institutional framework for monetary policy in the US and Alan Greenspan’s promotion of a highly discretionary approach to policy he euphemistically termed ‘risk management.’ It is hardly surprising then that markets view the Fed’s inflation-fighting credentials as being only as good as the next Fed Chairman.

I would be surprised if anyone were to raise similar questions about Stevens. The key difference is the RBA’s commitment to an inflation targeting regime. As it happens, the RBA’s inflation targeting framework is only very loosely defined and the associated governance framework remains thoroughly antiquated. The RBA makes up for this, however, by having articulated the relationship between policy and its inflation target. The RBA’s approach to policy is now reasonably well understood, in a way that Fed policy arguably isn’t. The RBA’s experience shows that even the most basic commitment to an inflation target can give a central bank credibility that doesn’t just walk out the door when the central bank head leaves.

Glenn Stevens will be speaking on The Conduct of Monetary Policy on Thursday. Should be an interesting speech.

posted on 08 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

RBA Rate Hike Probabilities

Taking a leaf from David Altig’s regular updates of Fed funds rate probabilities, below we show the probability of a 25 bp RBA rate hike at each of the monthly post-Board meeting announcement windows.

Probabilities are derived from 30 day interbank futures. These are not as liquid as 90 day bank bill futures, so bid prices are sometimes substituted for last trade prices. Only contracts for which there is currently open interest are shown. Although it is common to estimate implied probabilities from bill futures, interbank futures have the advantage of being a monthly rather than quarterly contract and there is no need to make assumptions about the (variable) premium of 90 day bill yields over the official cash rate.

Note that the RBA has no regularly scheduled meeting in January. The probability for January is based on an unscheduled ‘inter-meeting’ move on the first Wednesday of January.

posted on 06 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

North Korean Missile Launches for Fun and Profit II

Intrade’s North Korean missile launch contract is still trading, well after confirmation that the Norks launched at least six missiles, including a long-range Taepodong 2 that failed 40 seconds after launch. It is not clear whether Intrade are waiting for confirmation that the missiles did leave North Korean airspace, as per the contract, or are just asleep because of the 4 July holiday in the US. It could be that the post-launch trades will actually be unwound, back to the time of the first newswire reports of the missile launches. Price action below:

UPDATE: The Mainichi plots where the missiles landed:

posted on 05 July 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Take Out the Black Helicopters and You’ve Got Bill Gross

Caroline Baum’s Just What I Said, a collection of her Bloomberg columns from the late 1990s through to the early 2000s, contains a chapter on financial market conspiracy theories. She also reproduces some of the correspondence she received in response to these columns:

Do you really believe the US dollar is worth anything? Print what you want but look in the mirror if you want to see a “truly duped” conspirator! The black helicopter you hear…it is coming for you Caroline.

Take out the black helicopter references and you’ve almost got Bill Gross.

At least some of Baum’s mailbag would appear to be tongue-in-cheek, but you can never be entirely sure:

Yes, Caroline, there are black helicopters and the day of pecuniary recompense for the filthy idolaters of usury is at hand. Right now, even as I type, the reptilian mercenaries from Cygnet 61 and Zeta Reticuli are emerging from their base camps to lay siege to the money houses of Wall Street…Soon, you’ll start to notice iguana-like chalky stool droppings in banks and financial offices all over Wall Street. That is the sign it’s time to get out of town and head for the nearest subterranean shelter.

posted on 30 June 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Excess Liquidity’ and Asset Prices

The always sensible Stephen Jen tries to give his colleagues an education on so-called ‘excess liquidity’ and asset prices:

What fraction of the financial activities (hedge funds’ long positions in risky assets, carry trades, etc.) is financed through bank credit? I suspect that many analysts have put too much emphasis on the outdated concept of monetary aggregates driving asset prices. It is the yield curve — the opportunity cost of liquidity — that is key, in my view, in thinking about asset prices. Since central banks no longer have a great influence on the yield curves, it is perhaps not correct to blame the central banks for high asset prices. So much of the financial activities are not a function of what banks do, but the non-bank financial institutions such as hedge funds. The monetary aggregates say nothing about what these institutions are up to, what their perceived risk is, and what their risk taking appetite is.

Further, the Marshallian-k analysis actually says that the US base money to nominal GDP ratio has declined over the past decade, and the broad money to nominal GDP ratio being flat for the past few years. Those who believe there is a positive link between the Marshallian-k and asset prices have to explain away these facts. Moreover, we need to be very careful about three concepts: interest rates, asset prices and the real economy. Clearly, they are all related, but the Marshallian-k says very little about asset prices, though it might have some implications for inflation.

I suspect that even in relation to inflation, most of the analysis based on conventional measures of ‘excess liquidity’ is mistaken. Given the largely demand-determined nature of monetary aggregates, what is commonly thought of as ‘excess’ liquidity is more likely to be an ‘excess’ demand for money, reflecting portfolio choices between money, other assets and spending that only indirectly reflect central bank policy actions.

UPDATE: David Miles makes a similar point:

shifts in the private sector’s desire to hold a part of its total wealth in a subset of assets labelled ‘money’ (bank deposits of various sorts) are many and varied. To a large extent they reflect portfolio movements that are driven by shifts in the perceived attractiveness of a very wide range of assets. Quite what the interpretation of a shift in broad money for spending and inflationary pressures should be is absolutely unclear, until you drill down to what is driving it.

posted on 29 June 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Inflation Scare in Perspective

In the period since Bernanke’s appointment as Fed Chair, we have argued against the notion that Bernanke was somehow more dovish on inflation than his predecessor. Markets seem to have finally taken this in. Indeed, they now seem to be swinging in the other direction, with some very large hedge fund shorts in September eurodollar futures suggesting that some are looking for a 50 bp tightening from the Fed Thursday.

Alan Reynolds has a timely piece that puts the current inflation scare in perspective:

Others have expressed concern about “asset inflation” becoming embedded in core inflation. I cannot imagine how that idea ever gained credibility. The U.S. stock market boom of 1997-2000 was not followed by higher inflation. Neither was Japan’s land and stock boom of the late 1980s. Strength in asset prices in 1929 was perhaps the world’s worst predictor of inflation.

posted on 27 June 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 73 of 97 pages ‹ First < 71 72 73 74 75 > Last ›

|