Why Do Banks Pay Political Protection Money?

With the government, the opposition and the media all heavily engaged in gratuitous bank-bashing, few people have given much attention to the implications of tighter capital adequacy regulation for the cost of borrowing to consumers. RBA Governor Glenn Stevens was remarkably frank about the implications of increased regulation in a speech this week:

on the assumption that most of these regulatory changes go ahead, one effect will presumably be to make the process of financial intermediation more costly. The intention, after all, is that lenders will operate with more capital against the risks they are taking. But capital is not free; shareholders have to be induced to supply it, and it will have to be paid for. High-quality liquid assets typically carry lower yields too, so mandating higher liquidity will have some (modest) cost as well. Admittedly it can be argued that shareholders of financial institutions will have a less risky investment and so should be prepared to accept lower returns. But customers of financial institutions – depositors and borrowers – will also pay via higher spreads between what lenders pay for funds and what they charge for loans. That is, they will pay more ex ante to use a safer financial system, as opposed to taxpayers having to pay large costs ex post to re-capitalise a riskier system that runs into trouble.

Stevens’ posited trade-off between a safer financial system that is more expensive and one that is cheaper and riskier may only hold up to a point. His assumption that a more tightly regulated financial system is less likely to be bailed-out by taxpayers may not hold at all. As Stevens notes, careful attention needs to be given to whether the additional costs imposed by increased regulation will yield the desired benefits.

The increase in funding costs being passed on by the banks to their borrowers as a result of the financial crisis is not something we can do much about ex post, especially given that Australia is a price-taker in global capital markets. But we can do something about the future of bank capital regulation. Bashing the banks, while giving the government a free pass to tighten the regulation of capital without due attention to costs and benefits is perverse.

Perhaps even more perverse is the way the banks continue to fund the politicians who are actively seeking to damage their franchise. The AEC’s web site shows that the big four banks are all major donors to political parties (see, eg, Westpac’s return). No doubt the banks fear things would be even worse if they didn’t pay their political protection money, but it’s hard to see how.

posted on 10 December 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How to Reduce the Budget Deficit, Without Really Trying

The Australian economy just got bigger, thanks to the adoption of the new national accounting standard SNA08. The revised data raise the level of nominal GDP by 4.4% for 2007-08. As the government was quick to point out, this reduces the estimated budget deficit for 2009-10 from 4.7% to 4.5% of GDP, as well as the expected net debt to GDP ratio.

posted on 09 December 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Clive Hamilton as Reactionary Conservative

True socialists don’t support reactionary conservatives like Clive Hamilton:

it’s a sign of the decline of Left politics that a reactionary, pro-censorship sexual moraliser who hates the idea of working people enjoying a higher material standard of living could ever be considered left-wing…

It’s time that left-wingers stood up for their beliefs, rejected reactionaries like Hamilton and once again proudly said that we support industrial civilisation, the modern world, and more freedom and more material wealth for the working class. Any left-winger voting in the Higgins by-election this Saturday would do well to put Hamilton where he belongs: at the bottom of their preferences.

posted on 04 December 2009 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Abbott and McKibbin Need to Talk

Michael Stutchbury makes the case for Liberal leader Tony Abbott to adopt Warwick McKibbin’s hybrid ETS-cabon tax as a counter to Labor’s ETS. Former opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull was once sold on the McKibbin model when in government, but couldn’t be bothered making the case from opposition.

posted on 04 December 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Politics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Once a Leaker, Always a Leaker

The following observation from a London-based hedge fund trader is perhaps representative of offshore perceptions of monetary policy in Australia:

The RBA hiked rates again overnight, in line with leaks yesterday but contrary to some speculation at the height of the Dubai panic.

I don’t think there were any leaks on this occasion. Friday’s Reuters poll had all but one respondent expecting a 25 bp tightening, despite Dubai. But it shows that the perception that the RBA is a leaker is well entrenched in financial markets.

posted on 02 December 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

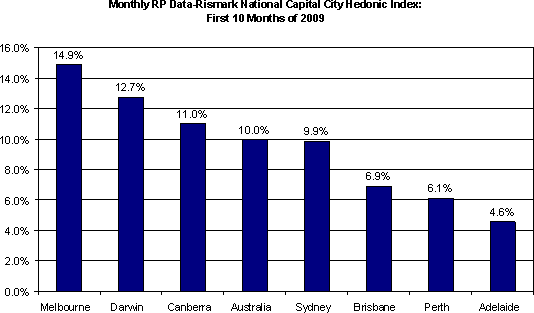

Australian House Prices Up 10% YTD

RP Data-Rismark have released the capital city hedonic house price index for October, showing house prices up 10% YTD.

Here’s what $1.85 million buys you in the Sydney suburb of Paddington:

posted on 30 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Who Would Want to Own an ETS?

Michael Stutchbury quotes Warwick McKibbin on the likely consequences of Labor’s emissions trading scheme:

Economist and Reserve Bank of Australia board member Warwick McKibbin warns the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme is “fundamentally unstable”, the price of permits will be “inherently volatile” and the Copenhagen agenda is in “total disarray”. “The political fallout from this is going to lead to changes,” he says.

The Coalition should let Kevin Rudd have full ownership of the fallout.

posted on 28 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Tony Abbott Offers Support for a Carbon Tax

Tony Abbott offers support for a carbon tax as an alternative to an ETS in today’s Australian:

many respected economists think a carbon tax would be more certain, less complex and far less open to manipulation than traded carbon permits.

In government, Malcolm Turnbull showed considerable interest in Warwick McKibbin’s proposal for a hybrid ETS-carbon tax. This story from February 2007 (’Turnbull gives tick to McKibbin carbon trading model’) quotes McKibbin as saying that Turnbull ‘understands it completely’, which makes Turnbull’s subsequent support for Labor’s ETS all the more inexcusable.

The Liberals who support Labor’s ETS do so largely because they are too lazy to argue for the alternative policy approaches they know to be better. I have heard several Liberal frontbenchers maintain that any policy with the word ‘tax’ in it won’t gain political support. They support an ETS only because they want to neutralise climate change as a political issue, not because they believe it to be the best policy. This is a monumental failure of leadership.

An obvious way forward for the Liberal Party, and for the Coalition, would be to commission McKibbin to design a hybrid scheme to take to the next election as an alternative to Labor’s ETS.

UPDATE: Joe Hockey goes begging for ideas on Twitter:

Hey team re The ETS. Give me your views please on the policy and political debate. I really want your feedback.

As David Cameron once said, too many tweets make a twat.

posted on 27 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Not Enough Houses

RBA Deputy Governor Ric Battellino, on why the housing investment share of GDP will have to rise.

posted on 26 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Bubbles’ in Everything

Chinese garlic.

posted on 26 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Too Many Malthusians

Brendan O’Neill, on why Malthusians are always wrong.

posted on 25 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

HSBC to Retail Gold Bugs: Get Your Own Damn Vault, Ours is Full

Gold is all about capital gain (or loss, as the case may be). After storage and insurance costs, gold has a negative yield. These costs may be about to go up, with retail gold bugs being booted out of gold storage facilities to make way for institutional investors. From the WSJ:

Amid gold’s rise—it has gained 32% this year and reached a record on Monday—investors have been loading up on bullion and coins. One big problem now is where to store it. The solution from HSBC, owner of one of the biggest vaults in the U.S.: somewhere else.

HSBC has told retail clients to remove their small holdings from its fortress beneath its tower on New York City’s Fifth Avenue. The bank has decided retail customers aren’t profitable enough and is demanding those clients remove their gold to make room for more lucrative institutional customers…

HSBC’s decision has created a logistical nightmare for both the investors and the security teams in charge of relocating the gold, silver and platinum to new vaults across the country…

HSBC is telling clients to either move their metal, or prepare for it to be delivered to their doorsteps. In a July letter, seen by The Wall Street Journal, HSBC said the precious metal “will be returned to the address of record… at your expense,” unless instructed otherwise. HSBC recommended clients move their holdings to Brink’s Global Services USA Inc., which has a vault in Brooklyn, N.Y.

posted on 25 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Gold

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

NZ Labour Loses its Way on Inflation

The Wall Street Journal has been running a series of articles on the impact of US dollar weakness on Asia-Pacific economies. In today’s edition, I write about New Zealand Labour’s abandonment of the consensus on inflation targeting:

Mr. Goff’s criticism of this dynamic misses the important benefits inflation targeting and its effects on the exchange rate bring to New Zealand. The dollar’s fluctuations help insulate the economy from external shocks, not least during the recent global financial crisis. When demand weakens in the rest of the world, the New Zealand dollar depreciates, making New Zealand’s exports more competitive. When external demand is strong, the currency rises, moderating export prices in New Zealand-dollar terms and restraining import price inflation. New Zealand’s floating exchange rate thus smoothes external demand and economic activity, making the central bank’s job of controlling inflation much easier.

Many exporters resent the role of the exchange rate in moderating New Zealand’s economic cycle, viewing their competitiveness as being sacrificed on the altar of inflation control. But the idea that New Zealand can ignore inflation and grow faster through easy money and a lower exchange rate is a short-sighted view, no matter how tempting. It ignores the fact that higher domestic prices resulting from inflation would ultimately undermine rather than promote international competitiveness. Economic growth and export success must ultimately be built on real factors such as productivity growth, not easy money and exchange rate depreciation.

Sinclair Davidson made similar arguments in relation to the Australian dollar in an earlier op-ed in the series.

posted on 23 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

The End of Inflation Targeting?

The leader of the opposition New Zealand Labour Party, Phil Goff, has announced the abandonment of his party’s support for inflation targeting by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand.

It was a Labour government that introduced the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act in 1989, making New Zealand a global pioneer in the practice of inflation targeting.

I have long suspected that the global trend towards increased central bank independence and inflation targeting would eventually be reversed. As I noted in my Bubble Poppers monograph, even the central banking community is increasingly divided on the issue.

If the bipartisan consensus in favour of inflation targeting can be shattered in New Zealand, it can happen anywhere.

posted on 19 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

Gold Price a Stock Rather than a Flow Equilibrium

With the nominal US dollar gold price posting record highs, I have an op-ed in today’s Age discussing the role of central banks and exchange rates in the determination of the gold price. Gold is a stock rather than a flow equilibrium and central banks command a large share of global stocks. However, exchange rates also have a large influence on the local currency returns to gold:

US dollar weakness has a positive valuation effect on the US dollar gold price, in the same way that it makes oil more expensive in US dollar terms. While a rising US dollar gold price is seen as symptomatic of a declining US dollar, this is true of US dollar commodity prices more generally.

Like other commodities, gold’s gains look less impressive in terms of currencies other than the US dollar. The Australian dollar exchange rate is positively correlated with the US dollar gold price, so that gains in US dollar terms are usually offset by Australian dollar appreciation. For an Australian investor, gold may be a good hedge against Australian dollar weakness, but actually increases exposure to US dollar weakness.

posted on 17 November 2009 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Gold

(5) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 38 of 111 pages ‹ First < 36 37 38 39 40 > Last ›

|