Peak Oil Nutters

The WSJ profiles some typical Peak Oilers:

It was around midnight one evening in November when Aaron Wissner shot up in bed, jolted awake by a fear: He wasn’t fully ready for the day when the world starts running low on oil.

Yes, he had tripled the size of the garden in front of the tidy white-clapboard house he shares with his wife and infant son. He had stacked bags of rice in his new pantry, stashed gold valued at $8,000 in his safe-deposit box and doubled the size of the propane tank in his yard.

“But I felt panicky, like I needed more insurance,” he says. So the 38-year-old middle-school computer teacher put on his jacket and drove to an all-night gas station, where he filled three, five-gallon jugs with gasoline.

“It was a feel-good moment,” says his wife, Kimberly Sager. “But he slept better.”

Not sure how a few bags of rice, a propane tank and a few grand in gold is meant to help with TEOCAWKI, but like they say, whatever helps you sleep at night.

At least someone is out there trying to give the peak oilers an education:

Three weeks after their first immersion, the couple drove to a peak-oil conference in Ohio, where lecturers showered them with statistics on demand curves and oil-field depletion rates. Then, at a conference in Denver, a man in a chicken suit called them crazies as he passed our fliers arguing that the world still has plenty of oil.

I’m with chicken suit guy.

posted on 26 January 2008 by skirchner in Culture & Society, Economics, Financial Markets

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

Who Killed the Baltic Dry Index?

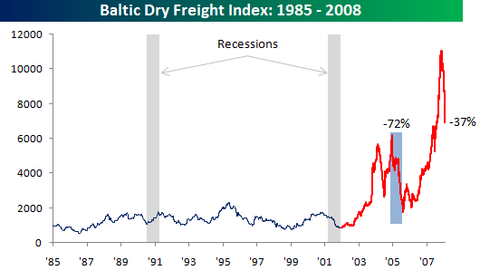

The Baltic Dry Index gets a lot of attention as a leading indicator and the signal it’s sending at the moment is certainly bearish. The index is 37% off its peak, having recorded some of its biggest one-day declines in the history of the series dating back to 1985. But a number of caveats are in order.

First, the index is US dollar denominated, and the November peak coincided with the lows in the US dollar index. Since then, the Curse of the Economist Magazine Cover has worked its magic and the US dollar index is off its lows. So at least some of the decline can be attributed to straightforward valuation effects.

Second, the massive run-up in the index probably tells us as much about supply constraints in the international shipping industry as it does the demand for commodities. Like most people, the shipping industry was caught short by the global commodities boom and building extra capacity will take time.

Third, as the following chart from Bespoke Investment Group shows, while previous recessions have been preceded by a downturn in the index, there are many more downturns in the index than there are recessions, including a much more dramatic downturn in 2004-05.

posted on 24 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Virtual Bank Run

Second Life suffers a real life banking system crisis:

the San Francisco company that runs the popular fantasy game pulled the plug on about a dozen pretend financial institutions that were funded with actual money from some of the 12 million registered users of Second Life. Linden Lab said the move was triggered by complaints that some of the virtual banks had reneged on promises to pay high returns on customer deposits…

The shutdown has caused a real-life bank run by Second Life depositors. Though some players managed to get their Linden dollars out, others are finding that they can no longer make withdrawals from the make-believe ATMs. As a result, they can’t exchange their Linden-dollar deposits back into real dollars. Linden officials won’t say how much money has been lost, but a run on another virtual bank in August may have cost Second Life depositors an estimated $750,000 in actual money.

The WSJ profiles one of the Second Lifers affected:

“Everyone thinks that because you’re losing play money, it excuses everything, but it’s convertible to real money,” says a Second Life player whose avatar is named UpMe Beam. On Sunday night, the female character was wandering topless through the virtual lobby of a Second Life bank called BCX Bank, where a sign said it was “not currently accepting deposits or paying interest.”

In real life, UpMe Beam is a man who says that he is a certified public accountant who has audited banks.

posted on 23 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Who Lost the ‘War on Inflation’?

The December quarter CPI is nothing less than disastrous. The 3.6% y/y average outcome for the statistical underlying measures is the worst result for underlying inflation since the great disinflation of the early 1990s and well above the 3.25% forecast in the RBA’s November Statement on Monetary Policy. It is sobering to recall that these measures are preferred by the RBA because they capture the persistent component of inflation that forecasts future inflation outcomes.

The government talks about a ‘war on inflation,’ but that war was lost by the RBA long before today’s CPI release. Amid all the finger-pointing between the federal government and opposition, few have bothered to point out that the Reserve Bank is the only public institution in Australia with a specific mandate to control inflation. Inflation is not some unfortunate exogenous event, unrelated to past monetary policy actions. The inflation target breach tells us that the RBA was not doing its job properly 12-18 months ago. In the US, the current and former Fed Chair are widely criticised for their supposed role in financial market problems not of their own making. Yet in Australia, the RBA’s senior officers still enjoy almost unimpeachable authority while at the same time failing to meet their core mandate.

If the RBA’s November Statement on Monetary Policy forecasts were realised, the RBA could perhaps have sat on its hands with a view to riding out the inflation target breach over the next 12 months and hope that international and domestic growth weaken sufficiently to return inflation to target in 2009. The risk in doing so is that the RBA ends up validating an acceleration in domestic inflation, requiring an even more aggressive tightening response down the track, with greater downside risks for the domestic economy. The tragedy of the RBA’s policy error on inflation is that it now has much less flexibility in responding to the deteriorating global growth outlook. The RBA can be expected to raise rates at its February Board meeting, despite continued equity market volatility and aggressive Fed easing.

posted on 23 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(7) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Fiscal Conservatism’ for All

Seems not everyone got the memo on ‘fiscal conservatism’:

KEVIN Rudd faces intensifying pressure from community groups for billions of dollars of new government spending, despite his promise of an austerity budget designed to ease pressure on inflation and interest rates.

As the Prime Minister told a business breakfast in Perth yesterday of his plans to cut spending in the 2008-09 budget, to be delivered in May, his office was being flooded with requests for more than $7 billion in spending on health, infrastructure and climate change.

posted on 22 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How to be a ‘Fiscal Conservative,’ Without Really Trying

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd is promising budget surpluses of 1.5% of GDP, as part of the government’s ‘war on inflation.’ Relative to the forward estimates contained in the previous government’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, this represents a fiscal contraction of a mere 0.2% of GDP.

Contrary to popular perception, Commonwealth fiscal policy is already the tightest it’s been in two decades. Looking at actual budget outcomes, as opposed to the forward estimates or the arbitrary counterfactuals the commentariat love to play with, the fiscal impulse (ie, the change in the budget balance as a share of GDP) has been either neutral or contractionary for the entire period since 2001-02. The underlying cash surplus has ranged between 1.5-1.6% of GDP since 2004-05, a GDP share not seen since the peak of the last cycle in the late 1980s. The automatic stabilisers would probably cough-up another surplus of 1.5% of GDP anyway, regardless of any contribution from discretionary policy actions.

The fiscal impulse has been largely irrelevant to inflation and interest rate outcomes in recent years. Today’s announcement suggests that is not about to change.

posted on 21 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Contrarian Indicator Alert: Mum & Dad Gold Bugs

The phones are running hot at the Perth Mint.

For an Australian dollar-denominated investor, gold should hold even less than usual appeal. As a major producer, Australia is already long gold. The Australian dollar is positively correlated with the US dollar gold price, so the Australian dollar gold price tends to underperform gains in the world price.

Little known fact: China became the world’s number one gold producer in 2007, according to GFMS Ltd’s annual Gold Survey.

posted on 21 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Paypal’s Exchange Rates

I regularly transfer US dollar Paypal balances to Australian dollars, which are normally converted at a 2.5% spread to wholesale spot rates. Paypal update their exchange rates twice daily. Since I have real-time access to wholesale spot rates, I can check the spread to spot and it is usually pretty close to 2.5%.

Recently, however, I have had a problem with Paypal failing to quote me updated exchange rates. I asked other Paypal account holders to get quotes on the USD-AUD exchange rate and they were being quoted different conversion rates that better reflected the 2.5% spread over spot rates.

I then checked to see what would happen if I logged into my account from a different computer, thinking it might be a caching issue. This finally resulted in an updated quote, but when I transferred a USD balance, the transfer was made at the former stale exchange rate I was being quoted previously.

Apart from being weird and different from my previous experience with Paypal, this is also inconsistent with Paypal’s Product Disclosure Statement required of financial service providers under Australian law. The exchange rate was not being updated regularly, the quoted spread was not the 2.5% mentioned in the PDS (at least not for me) and Paypal processed the conversions at a different rate to the one they quoted me immediately before I made the transaction.

My enquiries with Paypal have only elicited irrelevant boilerplate responses, so I’m thinking of referring the matter to the banking industry ombudsman. But before I do, I thought I would see if anyone else has had similar problems or had an explanation for what might be going on. I would actually be even more impressed to hear from someone with Paypal Australia. Any tech or financial journalists who would like to follow-up the story are also welcome to get in touch.

UPDATE (February 1): Paypal have finally acknowledged the error in an email to me:

We are actually aware of the issue and are working towards a resolution. We have added your account as another example of the error to expedite the urgency of the issue.

My suggestion would be that anyone with recent Paypal exchange rate conversions should check the rate they were given against wholesale spot rates. If the spread is not around 2.5%, you may want to get on to Paypal to seek a correction.

posted on 19 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Paypal Spot Rate Check Bleg

Would be grateful if any readers with a Paypal account and a USD balance could do a check on the USD-AUD exchange rate (not AUD-USD) quoted by Paypal. Note that there is no need to do an actual conversion, just go into ‘manage currency balances,’ where it will give you a quote without having to follow through with the conversion. I need the quote to five decimal places (try converting more than one US dollar to get the full quote). Potentially an interesting story in it. Will post a link from my site to yours as reward for your trouble. Thanks in advance. My email is info at institutional-economics.com.

UPDATE: No more quotes thanks. I have what I need.

posted on 18 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The CEO of Princeton Economics

Australia’s House Economics Committee may be cringe-inducing at times, but at least they generally know who they are talking to. Here’s Representative Marcy Kaptur, D-Ohio, grilling Fed Chairman Bernanke at a Budget committee hearing:

KAPTUR: Number three, seeing as how you were the former CEO of Goldman Sachs, what percentage level—oh, investment—were you not…

BERNANKE: No, you’re confusing me with the Treasury Secretary.

KAPTUR: I got the wrong firm?

BERNANKE: Yes.

KAPTUR: Paulson. Oh, OK. Where were you, sir?

BERNANKE: I was a CEO of the Princeton Economics Department.

KAPTUR: Oh, Princeton. Oh, all right. Sorry. Sorry.

(LAUGHTER)

Also caught on Youtube.

posted on 18 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

A Monetarist’s Work is Never Done

At the ripe old age of 92, Anna Schwartz is still giving the Fed a hard time:

“There never would have been a sub-prime mortgage crisis if the Fed had been alert. This is something Alan Greenspan must answer for,” she says.

While this is a widely held view, it is one I (respectfully, in this case) disagree with. It is hard to pin the under-pricing of risk in credit markets on monetary policy, as opposed to the innovative nature of the products involved. One can make a case that the amplitude of the most recent Fed funds rate cycle has been a factor in triggering widespread mortgage defaults, but that in turn reflected the preponderance of fixed rate mortgages in the US, which delayed the pass through of changes in the Fed funds rate to actual lending rates. The Fed was simply not getting much of an effect from changes in the Fed funds rate back in 2002 and 2003, which was also a factor in the very gradual re-tightening from mid-2004. If anything, this suggests that the US economy is not all that responsive to changes in official interest rates. The Fed stopped tightening and held rates steady for more than a year before the problems in credit markets emerged. It is hard to believe that the Fed triggered a credit shock by doing nothing for more than 12 months.

Few of the people who are now blaming the Fed were complaining about low interest rates in 2003. For its part, the Fed was fretting over the prospect of deflation instead. As the linked story notes:

Bernanke insists that the Fed has leant the lesson from the catastrophic errors of the 1930s. At the late Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday party, he apologised for the sins of his institutional forefathers. “Yes, we did it, we’re very sorry, we won’t do it again.”

Of course, there is no reason why we shouldn’t revise our analysis of events ex-post. But to blame subsequent events entirely on monetary policy is as unhelpful as it is implausible.

Still, you’ve got to hand it to Anna, fronting up to work at the NBER at 92. Most of us should be grateful to still be constructing coherent sentences at that age. If Friedman and Schwartz are any guide, monetarism is good for your health.

posted on 17 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(3) Comments | Permalink | Main

Yet Another ‘New Era’?

Having promised a ‘new era’ of Reserve Bank independence, the government is now promising the Reserve Bank a ‘new era of fiscal discipline’:

KEVIN Rudd and Wayne Swan have personally told the Reserve Bank of their determination to cut budget spending to reduce the need for further interest rate rises.

Following their meeting at the Reserve Bank’s Sydney headquarters with deputy governor Ric Battellino and Treasury secretary Ken Henry, Mr Swan said they had “flagged a new era of fiscal discipline”.

“It’s critical we demonstrate restraint as we frame our first budget, because that sends a clear message to the Reserve Bank,” Mr Swan said.

For reasons argued here, demand management is the wrong focus for fiscal policy and is not likely to have much impact on interest rates in any event. Rising interest rates are in fact symptomatic of economic strength, not weakness. What the government should fear most is that the RBA should start cutting interest rates, since that will be one of the first signs that the Australian economy has succumbed to the deteriorating global growth outlook. Rising interest rates should be the least of the government’s worries.

This is not to deny that Australia has an inflation problem, but all the finger-pointing between the government and the opposition misses the point that there is only one public institution in Australia with an explicit mandate to control the cyclical component of inflation, and that’s the Reserve Bank. Next week’s Q4 CPI release will likely show underlying inflation running above the RBA’s 2-3% medium-term target range. Given the lags between changes in official interest rates and inflation outcomes, this tells us that the RBA was not doing its job properly 12-18 months ago. The newly elected Labor government has inherited an inflation problem from the Reserve Bank, not the former Coalition government.

posted on 16 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(4) Comments | Permalink | Main

Douglas Holtz-Eakin on John McCain

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, economic policy adviser to Republican presidential candidate John McCain, talks to Bloomberg’s Tom Keene (mp3) about why McCain is the only candidate he has ever worked for.

posted on 15 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Aspirational Leadership

When it comes to the leadership of the federal parliamentary Liberal Party, Peter Costello remains all aspiration, no application:

Mr Costello is considering whether to remain in politics as a backbencher until Dr Nelson is deposed, then lead the Liberal Party to the next election with Malcolm Turnbull as his treasurer.

posted on 14 January 2008 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘Nice Bank You’ve Got There. Shame if Something Were to Happen to It’

Former Treasurer Peter Costello boasts that he thugged the banks better than Treasurer Swan:

Mr Costello claimed during his tenure as treasurer he was able to apply pressure to the bank’s chiefs not to raise rates as a result of the global credit crunch.

“They’ve taken the opportunity of a new treasurer who is not on top of the job to increase their margins and he came out and of behalf of the Labor Party he approved it,” Mr Costello said.

“I made it clear there were no grounds for the banks to increase interest rates,” Mr Costello said.

Treasury are not the only ones glad to see the back of Peter Costello.

posted on 11 January 2008 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 62 of 111 pages ‹ First < 60 61 62 63 64 > Last ›

|