Crowding Out and the BER

Crowding out effects were built-in to the BER:

BUILDERS and architects tendering for work under Julia Gillard’s school stimulus program were told to include a “cost escalation” of up to 10 per cent to cover the expected inflationary impact of the scheme.

The hidden cost of the Building the Education Revolution, revealed in documents submitted to a Victorian parliamentary inquiry, suggests that as much as $250 million of taxpayers’ money could have been spent to cover a surge in building material and labour costs created by the state’s $2.5 billion share of the stimulus program.

Contract details provided by an architecture firm reveal it was required by the Victorian Education Department to provide a 7 per cent “contingency fee” and a 10 per cent “cost escalation” in the tenders it submitted for work on four primary schools in Melbourne’s east.

Government sources confirmed last night the department specifically included escalation costs in BER projects “because the stimulus was going to be a significant injection into the market/economy and prices could be expected to increase with greater levels of work being undertaken”.

posted on 29 July 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Greg Mankiw versus Ken Henry on the Role of Economists in Public Policy

The following observation by Greg Mankiw could have been written in response to Ken Henry’s recent lament about the role of economists in public policy:

economists are social scientists, not politicians. And whether they work for the government or have the luxury of merely observing the scene from an ivory tower, the integrity of the profession and the importance of the work involved demand that they be subjected to critical judgment; they must be compelled always to submit their assumptions, data, models, and conclusions to careful scrutiny. The foremost job of economists is not to make the lives of politicians easier, but to think through problems, to examine all the available information about the problems’ causes and potential treatments, and to propose the solutions most likely to work.

This is a simple point, but one that is easy to forget. As Milton Friedman once put it: “The role of the economist in discussions of public policy seems to me to be to prescribe what should be done in light of what can be done, politics aside, and not to predict what is ‘politically feasible’ and then to recommend it.”

In a time of economic uncertainty and political turmoil, we economists — both in and out of government — could hardly do better than to follow Friedman’s sage advice.

posted on 24 July 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

An Unlikely RBA Research Discussion Paper

Imagine if you will the RBA publishing a Research Discussion Paper that reached the following conclusions:

despite a relatively stable total fiscal impulse the effectiveness of spending shocks in stimulating economic activity has decreased over time. Short-run spending multipliers increased until the late 1980s when they reached values above unity, but they started to decline afterwards to values closer to 0.5 in the current decade. Long-term multipliers show a more than two-fold decline since the 1980s. These results suggest that other components of aggregate demand are increasingly being crowded out by spending based fiscal expansions. In particular, the response of private consumption to government spending shocks has become substantially weaker over time.

rising government debt is the main reason for declining spending multipliers at longer horizons, and thus increasingly negative long-run consequences of fiscal expansions. We interpret this finding as an indication that further accumulating debt after a spending shock leads to rising concerns on the sustainability of public finances, such that agents may expect a larger fiscal consolidation in the future which depresses private demand and output. We also find that a stronger response of the short-term nominal interest rate goes along with declining spending multipliers. This result is consistent with an increasingly offsetting reaction of monetary policy to the expansionary fiscal shock.

The extract is from a European Central Bank Working Paper and the conclusions reached are in relation to the euro area. Don’t hold your breath waiting for the RBA to publish a similar study of activist fiscal policy in Australia.

posted on 21 July 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

No Future in Future Funds

I have an op-ed in today’s Australian arguing that improved fiscal responsibility legislation is a better approach to managing the fiscal consequences of terms of trade cycles than sovereign wealth funds such as the existing Future Fund:

a sovereign wealth fund provides no guarantee current revenue will be spent more wisely in the future than it is today.

If governments are unwilling to commit to binding fiscal responsibility legislation that improves on the existing Charter of Budget Honesty, there is no reason to believe greater use of a sovereign wealth fund will lead to better long-term fiscal management.

Part of the op-ed that hit the cutting room floor noted that Australia is not like Norway, Timor Leste or Nauru, dependent on a single export commodity. Australia’s resource endowment and overall economy is much more diversified, making Australia less vulnerable to some of the macroeconomic and other problems associated with dependence on a single commodity export.

posted on 15 July 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘The Full Omelette’: Treasury After the RSPT

The post-RSPT backlash against Treasury:

A key figure in the negotiating team of one of the major mining houses puts it more bluntly: “Clearly Ken Henry was on a mission from God. The fact that Treasury had got religion was not the biggest surprise. What we were especially amazed at was the level of sheer naivete and incompetence. The grasp of fundamental economics—more specifically commercial reality—was barely past what you learn in year 12 at high school.”…

In the end the miners were not provided with Treasury’s modelling until last Wednesday. These were the numbers that, according one insider, had come from “planet Mars”.

“They had made it up and had no idea how to back it up. It was like sitting university professors down to lecture primary school students,” one of the miners’ advisers claimed yesterday.

posted on 04 July 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ricardian Equivalence in Australia

Shane Brittle has completed a PhD thesis that is the most comprehensive examination of the issue of Ricardian equivalence and related questions in an Australian setting. Brittle estimates a long-run private saving offset to changes in public saving of around one-half. One interesting conclusion from the thesis is that around 80% of the Howard government’s tax cuts were saved, an empirical refutation of the ‘tax cuts lead to higher interest rates’ nonsense of a few years ago.

posted on 16 June 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

‘A Politician with Rage at His Core’

Samantha Maiden reviews David Marr’s profile of Kevin Rudd and the barely contained rage that motivates the Prime Minister. At the same time, Paul Kelly discusses Kevin Rudd’s Whitlamite experiment in big government:

Kevin Rudd is taking Australia on to a new policy trajectory of state intervention, control and faith that “government knows best”.

This looms as the decisive judgment on the Rudd era. It constitutes a break from Australia’s post-1983 tradition of pro-market, middle-ground economic reform. It is not necessarily unpopular but raises the alarm that Australia is marching a false policy path…

Yet Labor keeps moving in the direction of Rudd’s maiden speech philosophy. “I believe unapologetically in an active role for government,” he said. He repudiated the view that “markets rather than governments are better determinants of not only efficiency but also equity”. It is a sweeping statement. And it is entirely consistent with his interventionist car industry agenda, plans to build 12 new submarines, compulsion for new spending programs, government-directed nation-building across several fronts and declared timetables to reduce homeless levels and close the gaps for indigenous Australians.

The unifying idea is that government direction or intervention or ownership is the way forward. It fits into a more personal theme: Rudd knows best.

Sadly, Rudd has no shortage of enablers, including the likes of Paul Kelly, who continues to cheer the fiscal stimulus in the linked story. Kelly does not seem to understand that the problems with the stimulus spending are not simply problems of implementation.

posted on 07 June 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy, Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The UK’s Office of Budget Responsibility

The new coalition government in the UK has handed responsibility for its economic and fiscal forecasts to an independent Office of Budget Responsibility:

The Chancellor said the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) would give greater credibility to the figures that were unveiled on Budget day…

Accusing the previous Labour government of consistently misleading the public, Mr Osborne said the OBR would be in charge of growth and borrowing forecasts.

“Again and again, the temptation to fiddle the figures, to nudge up a growth forecast here or reduce a borrowing number there, to make the numbers add up has proved too great, and that is a significant part of the reason for our current problems,” he said.

“I am the first Chancellor to remove the temptation to fiddle figures by giving up control of the economic and fiscal forecasts. I recognise that this will create a rod for my back down the line.

“That is the whole point. We need to fix the Budget to fit the figures, not fix the figures to fit the Budget.”

Robert Carling and I proposed a similar model for Australia in our CIS Policy Monograph, Fiscal Rules for Limited Government.

posted on 24 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Ken Henry and the Club of Rome

Terry McCrann on the resource scarcity assumptions motivating the RSPT:

It is also clearly founded on the assumption of a long-term—Club of Rome-flavoured—secular upward trend in commodity prices. Thanks to China and India, demand is ever rising, while supply is limited. There’s only so much copper, etc. We must surely run out.

This is a merging of Henry’s green tendencies with his intellectual faith in the purity and reliability of econometric modelling—a blend most dramatically on view in the ludicrous Treasury modelling of the emissions trading scheme.

Henry implicitly rejects the view that non-fuel commodity prices are necessarily on a long-term secular down-trend—as revealed in graphs of aluminium and copper prices through the 20th century.

“Observed trends are sensitive to the commodity selected and the choice of time period,” he notes. So a chart of the copper price over a shorter period, between 1930 and 1970, showed the price “trended quite sharply upward”.

What he didn’t do was reproduce the shorter time period graph for aluminium. I don’t know why. It would have shown the exact opposite of the copper graph—the aluminium price on a long and short down trend.

There is more to this than selective charting. The anti-Club-of-Rome perspective—reality—of mineral supply and demand is not compatible with the logic of the super-profits tax. There is no alternative to developing our resources, even if the government takes 40 per cent more of the profits.

More exquisite was the graph with which he started his presentation. Taken from the budget, it showed the difference between Treasury’s GDP forecasts and projections in last year’s budget, and the ones in this year’s document.

What a very big difference a year makes. Henry is completely unable to see how Treasury’s failure, and the failure of its models, to get even close to predicting the present.

posted on 22 May 2010 by skirchner in Commodity Prices, Economics, Fiscal Policy

(1) Comments | Permalink | Main

Privatisation Can Mitigate Greek Debt Crisis

Alan Meltzer on privatisation as a partial solution to Greek debt problems:

Much of Greece’s industry and commerce, including much of the tourist industry, is owned by the state. It should be sold with the proceeds used to reduce public debt. That would make the remainder of the debt more sustainable and transfer workers to the private sector where competitive pressures for lower wages and increased productivity would more closely align employment costs and reality. If the socialist government returned more of the economy to the private sector, Greece would have a better chance of economic recovery.

posted on 21 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Case Against (Another) Australian Sovereign Wealth Fund

As if the Future Fund were not bad enough, there are those (really just Paul Cleary, who thinks Australia is like Timor Leste, where he spent too much time) who argue that Australia should establish another sovereign wealth fund as a revenue stabilisation fund to smooth out the budgetary implications of terms of trade shocks. In yesterday’s speech to ABE, Treasury Secretary Ken Henry argued against the idea, while pretending not to:

I don’t want to pre-empt a debate on these matters. But I will make a few observations.

First, if the revenue surge is regarded as likely to be long-lived, the alternative of tax cuts – permitting the private sector to make its own saving and investment decisions – should always be considered first.

Second, of the various objectives, the proposition that a sovereign wealth fund can be used to impose discipline on government spending is most problematic. Sovereign wealth funds that have been in place around the world have not been as effective in imposing spending discipline as many seem to believe. IMF research has found that there is no statistical evidence that such funds impose any effective expenditure restraint.6 Even if rules are put in place to restrict access to the fund, in the absence of liquidity constraints, a government that wants to finance an increase in current spending can borrow against the security of the fund. Money is, after all, fungible.

Third, stabilisation, consumption smoothing and exchange rate sterilisation are not dependent upon having a sovereign wealth fund. That is to say, these objectives could just as well be achieved within the context of the overall budget strategy.

Fiscal stabilisation can be achieved without drawing on a sovereign wealth fund, as demonstrated in Australia’s response to the global financial crisis and international recession.

Consumption smoothing can alternatively be achieved in the Australian context by investments in human capital and high quality public infrastructure or through contributions to individuals’ superannuation accounts.

And a country experiencing large gross flows, both inward and outward, of both equity and debt, doesn’t have to take an explicit decision to invest the proceeds of fiscal surpluses in foreign assets in order that those surpluses put downward pressure on the nominal exchange rate. That is, using budget surpluses to repay debt, or even to purchase another financial asset domestically, would have the same effect.

posted on 19 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(2) Comments | Permalink | Main

The Acid Test for the Euro

John Cochrane explains why the Greek bail-out tells you everything you need to know about the euro:

Greek bondholders are not being asked to miss a single interest payment, reschedule a cent of debt, suffer any write-down, take a forced rollover or conversion of short to long-term debt, or any of the other messy ways insolvent sovereigns deal with empty coffers. Those who bought credit default swaps lose once again…

The only way to solve the underlying euro-zone fiscal mess (and our own) is to slash government spending and to focus on growth. Countries only pay off debts by growing out of them. And no, growth does not come from spending, especially on generous pensions and padded government payrolls. Greece’s spending over 50% of GDP did not result in robust growth and full coffers. At least the looming worldwide sovereign debt crisis is heaving “fiscal stimulus” on the ash heap of bad ideas.

posted on 18 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Bernard Keane Wrong on Tax Expenditures

Writing in Crikey, Bernard Keane says:

Every year the government forgoes more than $100 billion in tax revenue courtesy of exemptions and concessions in the tax system.

This is an all-too-common journalistic error that stems from a misreading (or failure to read) the Treasury’s Tax Expenditures Statement. Here is how Treasury describes its methodology:

The estimates of tax expenditures in this statement are prepared under the ‘revenue forgone’ approach which calculates the value of tax expenditures in terms of the benefit to the taxpayer of the tax provisions concerned…

Revenue forgone estimates differ from budget revenue estimates because they are estimated relative to different benchmarks…It does not necessarily follow that there would be an equivalent increase to government revenue from the abolition of the tax expenditure.

the revenue forgone approach requires only a single consistent assumption regarding behavioural responses to removing a concession (no behavioural change) which allows the value of a tax concession to be based on the actual (or projected) level of transactions.

The critical assumption of no behavioural change invalidates Keane’s inferences about the implications of various tax expenditures for budget revenue.

posted on 14 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

How to Reduce the Budget Deficit, Without Really Trying

According to Treasurer Wayne Swan, the government is set to preside over the ‘most substantial fiscal consolidation in Australia’s modern history’, leading the federal budget back into surplus by 2012-13. The OECD’s glossary of statistical terms defines fiscal consolidation as ‘a policy aimed at reducing government deficits and debt’. But the policy measures in the government’s 2010-11 Budget make the budget balance worse, not better. The projected improvement in the budget bottom line is more than fully accounted for by changes in forecasting assumptions. The government wants to claim credit for an improvement in the budget outlook that is entirely a product of its earlier forecasting errors.

The government’s forecast of a faster return to surplus is not evidence of fiscal discipline, but of the sensitivity of the fiscal outlook to underlying assumptions. Similarly, the claim that the Australian economy performed better than expected through the global financial crisis is evidence, not of the success of activist fiscal policy, but the fact that the forecasts on which that policy was based were too pessimistic.

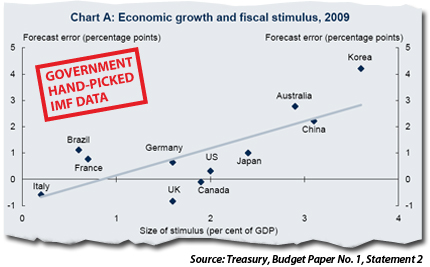

The budget papers include a chart showing that the size of fiscal stimulus was positively correlated with the size of the forecast error for economic growth across 11 countries. The government wants us to conclude that its fiscal stimulus is to be credited with better than expected economic performance. But causality could just as easily run the other way: the large forecasting error led to excessive stimulus. Since the government’s earlier budget forecasts already had the expected impact of the stimulus measures built into them, its assumptions about the effectiveness of stimulus must have been incorrect as well. Indeed, the government now claims that the multipliers it used to estimate the impact of the stimulus were too small. But this just concedes the point that the government has no idea how effective its fiscal policy measures really were in stimulating economic activity.

What matters is the not the budget forecasts, but the policy outcomes. The Rudd government has presided over the biggest growth in federal spending since Gough Whitlam. It is now committed to keeping real growth in federal spending below 2%. But that’s just a forecast. As the old disclaimer says, outcomes may vary.

UPDATE: Sinclair Davidson includes the data Treasury could have used, but didn’t:

posted on 12 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Robert Barro’s Great Depression Reading List

Robert Barro’s reading list on the economics of the Great Depression. I would add that there is a shorter version of Friedman and Schwartz’s A Monetary History of the United States dealing specifically with the Depression: The Great Contraction, 1929-33, recently re-published by PUP.

Barro on stimulus:

There’s a strong tendency for the economy to recover on its own, as long as it’s not subject to further new shocks, so a likely scenario is that that is what will happen today as well. And then the Obama administration will say that it’s because of our policy that things recovered, and there won’t be any way to prove whether that’s right or wrong.

posted on 16 April 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink | Main

Page 4 of 9 pages ‹ First < 2 3 4 5 6 > Last ›

|