|

The US Senate passes what is potentially the most devastating regulatory attack on the foundations of US prosperity since the New Deal. Pete Wallison blames Republican populism:

How did this happen? After Scott Brown’s election to Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat, Republicans had the votes to prevent the closing of debate and keep the Dodd bill off the Senate floor. They could have argued that legislation this important should not be rushed through Congress. They could have pointed out that there were no hearings on most of the major elements of the bill. And they could have reminded the Democrats that the commission Congress appointed to advise them on the causes of the financial crisis would not be reporting until mid-December.

They did none of these things. Instead they backed away from cloture, allowing the legislation to go to the Senate floor where the bill, bad enough to begin with, became steadily worse. Amendments to allow the Fed to regulate interchange fees on debit cards, and to force banks out of the derivatives business are only two examples. This was fully predictable, since the unpopularity of Wall Street and the banks would encourage amendments hostile to business and finance.

Why was the GOP unable to stand united and filibuster the bill before it reached the Senate floor? For the least meritorious of reasons, it seems: unwillingness to go to the voters this November without having done “something” to punish Wall Street and the banks.

posted on 21 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Rule of Law

(0) Comments | Permalink

Alan Meltzer on privatisation as a partial solution to Greek debt problems:

Much of Greece’s industry and commerce, including much of the tourist industry, is owned by the state. It should be sold with the proceeds used to reduce public debt. That would make the remainder of the debt more sustainable and transfer workers to the private sector where competitive pressures for lower wages and increased productivity would more closely align employment costs and reality. If the socialist government returned more of the economy to the private sector, Greece would have a better chance of economic recovery.

posted on 21 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

That the Australian dollar should underperform the euro is not entirely surprising, given that AUD typically suffers from the global risk aversion trade, along with commodities and other assets that are perceived as risky. What is harder to explain is AUD’s underperformance against the New Zealand dollar, given that NZD is typically viewed as being even riskier than AUD. A CTA I spoke to earlier in the week said that the message from the broker dealers is that foreign capital is exiting Australia because of the proposed RSPT. Australian equity markets underperformed the Nikkei and Hang Seng yesterday.

posted on 21 May 2010 by skirchner in Commodity Prices, Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

As if the Future Fund were not bad enough, there are those (really just Paul Cleary, who thinks Australia is like Timor Leste, where he spent too much time) who argue that Australia should establish another sovereign wealth fund as a revenue stabilisation fund to smooth out the budgetary implications of terms of trade shocks. In yesterday’s speech to ABE, Treasury Secretary Ken Henry argued against the idea, while pretending not to:

I don’t want to pre-empt a debate on these matters. But I will make a few observations.

First, if the revenue surge is regarded as likely to be long-lived, the alternative of tax cuts – permitting the private sector to make its own saving and investment decisions – should always be considered first.

Second, of the various objectives, the proposition that a sovereign wealth fund can be used to impose discipline on government spending is most problematic. Sovereign wealth funds that have been in place around the world have not been as effective in imposing spending discipline as many seem to believe. IMF research has found that there is no statistical evidence that such funds impose any effective expenditure restraint.6 Even if rules are put in place to restrict access to the fund, in the absence of liquidity constraints, a government that wants to finance an increase in current spending can borrow against the security of the fund. Money is, after all, fungible.

Third, stabilisation, consumption smoothing and exchange rate sterilisation are not dependent upon having a sovereign wealth fund. That is to say, these objectives could just as well be achieved within the context of the overall budget strategy.

Fiscal stabilisation can be achieved without drawing on a sovereign wealth fund, as demonstrated in Australia’s response to the global financial crisis and international recession.

Consumption smoothing can alternatively be achieved in the Australian context by investments in human capital and high quality public infrastructure or through contributions to individuals’ superannuation accounts.

And a country experiencing large gross flows, both inward and outward, of both equity and debt, doesn’t have to take an explicit decision to invest the proceeds of fiscal surpluses in foreign assets in order that those surpluses put downward pressure on the nominal exchange rate. That is, using budget surpluses to repay debt, or even to purchase another financial asset domestically, would have the same effect.

posted on 19 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(2) Comments | Permalink

Bob McTeer debunks the inflation fears of fever-swamp Austrians:

What am I missing? I keep hearing people on financial TV say things like “The Fed keeps pumping out the dollars,” “The Fed keeps monetizing the debt.”

Then I go look up money-growth charts. I can’t find all this excessive money creation that is monetizing the debt and is about to create a breakout in inflation. Not M1; not M2…

To repeat the obvious, because others won’t, money growth is almost flat. Flat money growth does not cause inflation—especially when we have enormous slack in the economy along with rapid productivity growth and declining unit labor cost. We may get inflation in the next few years, but, if so, it will be based on money growth yet to happen. It hasn’t happened yet.

posted on 19 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Monetary Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

John Cochrane explains why the Greek bail-out tells you everything you need to know about the euro:

Greek bondholders are not being asked to miss a single interest payment, reschedule a cent of debt, suffer any write-down, take a forced rollover or conversion of short to long-term debt, or any of the other messy ways insolvent sovereigns deal with empty coffers. Those who bought credit default swaps lose once again…

The only way to solve the underlying euro-zone fiscal mess (and our own) is to slash government spending and to focus on growth. Countries only pay off debts by growing out of them. And no, growth does not come from spending, especially on generous pensions and padded government payrolls. Greece’s spending over 50% of GDP did not result in robust growth and full coffers. At least the looming worldwide sovereign debt crisis is heaving “fiscal stimulus” on the ash heap of bad ideas.

posted on 18 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

Eric Falkenstein goes in search of Nouriel Roubini’s 2006 speech to the IMF:

In Michiko Kakutani’s NYT book review of Nouriel Roubini’s Crisis Economics, and in the book’s foreward, a September 7, 2006 IMF speech is highlighted as containing specific warnings about US housing, and how this would lead to a financial contagion. This would seem to be highly prophetic. So I went to his website looking for this speech. It linked to something from 2009. To get to this point I had to register at his site, and they sent me a an email message, asking what I wanted to know (they seem to sell different levels of access at the Roubini Global Economics—a sort of CNBC with only negative spin). I asked to see the 2006 speech mentioned in the NYT book review, and they pointed me towards a different speech in 2006 that was rather vague. So I asked again for the rather prominent September 7 2006 speech, and they did not answer.

I bet the speech mentions not merely the housing problems, but a bunch of things that could go wrong that did not, which would suggest indiscriminate crisis prediction that is not so impressive.

Here is an IMF account of the speech. Oliver Hartwich and I also referenced the speech in our profile of Roubini for Juedische Allgemeine (English version here), for which we had to rely on second-hand accounts.

posted on 18 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Matt Ridley discovers Julian Simon:

Furthermore it is possible, indeed probable, that by 2110 humanity will be much much better off than it is today and so will the ecology of our planet. This view — which I shall call rational optimism — may not be fashionable but it is compelling.

Rational optimism holds that the world will pull out of its economic and ecological crises because of the way that markets in goods, services and ideas allow human beings to exchange and specialise for the betterment of all. But a constant drumbeat of pessimism usually drowns out this sort of talk. Indeed, if you dare to say the world is going to go on getting better, you are considered embarrassingly mad.

If, on the other hand, you say catastrophe is imminent, you can expect a MacArthur Foundation genius award…

The more human beings diversified as consumers and specialised as producers, and the more they exchanged goods and services, the better off they became. And the good news is there is no inevitable end to this process.

As more people are drawn into the global division of labour and more people specialise and exchange, we will all become wealthier. Along the way, moreover, there is no reason why we cannot solve the problems that beset us — economic crashes, population explosions, climate change, terrorism, poverty, Aids, depression, obesity.

posted on 17 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics

(4) Comments | Permalink

Cliffford Asness and Aaron Brown on the rise of the Treasury-financial complex:

The Dodd bill is perfectly designed to create the largest and most powerful crony system in history. It’s not that the people, regulator or regulated, are personally corrupt. It’s that the system will itself select for, reward and enforce corruption.

No financial professional will be able to turn down a “request” for a campaign contribution, and all financial institutions will hire former staffers as advisers or directors. No regulator can afford to antagonize a potential future employer. Regulators themselves must kowtow to Congress, which can use them for under-the table subsidies to favored groups. None of this is new to politics, of course, but the scale and lack of defined powers are.

posted on 15 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets, Rule of Law

(0) Comments | Permalink

Writing in Crikey, Bernard Keane says:

Every year the government forgoes more than $100 billion in tax revenue courtesy of exemptions and concessions in the tax system.

This is an all-too-common journalistic error that stems from a misreading (or failure to read) the Treasury’s Tax Expenditures Statement. Here is how Treasury describes its methodology:

The estimates of tax expenditures in this statement are prepared under the ‘revenue forgone’ approach which calculates the value of tax expenditures in terms of the benefit to the taxpayer of the tax provisions concerned…

Revenue forgone estimates differ from budget revenue estimates because they are estimated relative to different benchmarks…It does not necessarily follow that there would be an equivalent increase to government revenue from the abolition of the tax expenditure.

the revenue forgone approach requires only a single consistent assumption regarding behavioural responses to removing a concession (no behavioural change) which allows the value of a tax concession to be based on the actual (or projected) level of transactions.

The critical assumption of no behavioural change invalidates Keane’s inferences about the implications of various tax expenditures for budget revenue.

posted on 14 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

From the WSJ:

The working theory among traders and others involved in the exchange meltdown is that the “Black Swan”-linked fund may have contributed to a “Black Swan” moment, a rare, unforeseen event that can have devastating consequences.

As Eric Falkenstein notes, this episode may shed light on how Nassim Taleb really makes his money:

All the while, however, he makes huge fees, because 1% on $4B is a lot of money, and his wealth will serve as proof that he’s an investing genius. More importantly, he then selectively presents to a credulous press he makes billions off his market savvy.

Gee, someone should write a book about blow-hard traders who misrepresent their track records and take excessive risk with other-people’s money, all due to cognitive biases they are too shallow to notice in themselves. Oh yeah, Taleb has done that! I guess his insider status gives him better insight.

posted on 14 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(1) Comments | Permalink

The NSW government has introduced yet another new tax on housing transactions. Yesterday, I gave a post-budget presentation to a business group in Western Sydney, together with Westpac’s Matthew Hassan. Matthew presented some stunning charts showing the growth in the tax burden on housing in each state, with NSW the clear winner. Indeed, the tax burden on a new house and land package on Sydney’s suburban fringe is now such as to make it unprofitable to bring to market, which helps explain why new housing supply in the state is running at 1950s levels.

If only some of the outrage directed against negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions by ignorant journalists and commentators could be marshalled against the taxes and charges that are really responsible for putting upward pressure on house prices.

posted on 13 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, House Prices

(4) Comments | Permalink

According to Treasurer Wayne Swan, the government is set to preside over the ‘most substantial fiscal consolidation in Australia’s modern history’, leading the federal budget back into surplus by 2012-13. The OECD’s glossary of statistical terms defines fiscal consolidation as ‘a policy aimed at reducing government deficits and debt’. But the policy measures in the government’s 2010-11 Budget make the budget balance worse, not better. The projected improvement in the budget bottom line is more than fully accounted for by changes in forecasting assumptions. The government wants to claim credit for an improvement in the budget outlook that is entirely a product of its earlier forecasting errors.

The government’s forecast of a faster return to surplus is not evidence of fiscal discipline, but of the sensitivity of the fiscal outlook to underlying assumptions. Similarly, the claim that the Australian economy performed better than expected through the global financial crisis is evidence, not of the success of activist fiscal policy, but the fact that the forecasts on which that policy was based were too pessimistic.

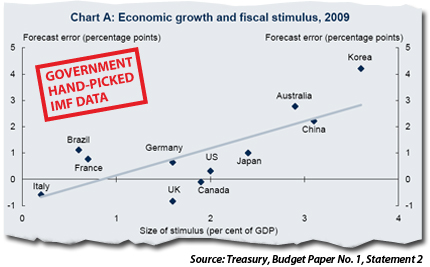

The budget papers include a chart showing that the size of fiscal stimulus was positively correlated with the size of the forecast error for economic growth across 11 countries. The government wants us to conclude that its fiscal stimulus is to be credited with better than expected economic performance. But causality could just as easily run the other way: the large forecasting error led to excessive stimulus. Since the government’s earlier budget forecasts already had the expected impact of the stimulus measures built into them, its assumptions about the effectiveness of stimulus must have been incorrect as well. Indeed, the government now claims that the multipliers it used to estimate the impact of the stimulus were too small. But this just concedes the point that the government has no idea how effective its fiscal policy measures really were in stimulating economic activity.

What matters is the not the budget forecasts, but the policy outcomes. The Rudd government has presided over the biggest growth in federal spending since Gough Whitlam. It is now committed to keeping real growth in federal spending below 2%. But that’s just a forecast. As the old disclaimer says, outcomes may vary.

UPDATE: Sinclair Davidson includes the data Treasury could have used, but didn’t:

posted on 12 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Fiscal Policy

(0) Comments | Permalink

I have an op-ed in today’s Australian on the issue of population growth and capacity constraints:

Much of the debate has been predicated on the mistaken view that population growth and immigration policy should be conditioned on existing capacity constraints, whether it be in the areas of housing, infrastructure, water or the environment. Taken to their logical extreme, many of these concerns would have ruled out the founding of the colony of NSW in 1788, when the infrastructure to support the first European settlers was nonexistent.

A growing population adds to demand for existing resources but also supplies the incentives and additional human capital essential to overcoming temporary resource constraints.

Yes, this is the same op-ed that ran in the Canberra Times some time ago. It got another run as a result of an error made at the Oz. Not that I’m complaining, but we don’t generally make a practice of double-dipping on op-eds.

posted on 12 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Population & Migration

(0) Comments | Permalink

Phil Levy on the return of efficient markets:

One of the great memes to emerge from the financial crisis was that economists had no idea what they were talking about. After all, professional economists had urged deregulation and faith in markets; an internet full of amateur economists could easily see that such misguided nuggets of advice were solely responsible for all the woe that ensued.

This analysis was always a bit problematic. First, we may need a bit more perspective to properly attribute causality in the crisis. The snap analyses have been politically convenient, in that they have supported snap policy responses, but they have their flaws. For example, what about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? These were hardly paragons of unfettered market extremism and they were central to the housing bubble and to the cost of the eventual government bailout. I know firsthand that this was a crisis foretold by economists, since I served as a senior staff economist for Greg Mankiw when he chaired President Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers. Greg, working with excellent economists like Karen Dynan, now of Brookings, was vocal about the dangers posed by these government-sponsored enterprises and helped formulate proposals for reining them in. Congress blocked the proposals.

posted on 08 May 2010 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Page 31 of 111 pages ‹ First < 29 30 31 32 33 > Last ›

|