|

Kevin Hassett argues that US Q3 GDP may play a role in the upcoming US congressional elections:

here is the kicker for Republicans: The data calendar indicates that GDP for the third quarter will be reported by the Bureau of Economic Analysis on Oct. 27, right before Americans enter the voting booths.

You might call it the “October surprise,” but in this case, economists will have seen it coming. Republicans, who have found themselves in the political equivalent of a nightmarish ballgame for some months now, will probably not be surprised that this break has gone against them as well.

My associates at Action Economics are arguing that any ‘October surprise’ will be up:

The market seldom watches U.S. wholesale trade reports, but this morning’s figures have revealed a robust growth trajectory for both sales and inventories that has further reduced prospects for a meaningful slowdown in GDP growth in Q3, as some still fear. We have not revised our 2.7% GDP growth estimate for Q3, but economists focused on a “1-handle” will have difficulty supporting such low forecasts.

Meanwhile, Nouriel Roubini is arguing that falling oil prices are a negative for the US economic outlook. Back when Nouriel was forecasting oil at $100/barrel, it was a different story:

I fully agree that oil prices will remain high for a long time; worse, they are likely to significantly rise towards $100 in the medium term (and some are already expecting oil at $90 by year end). Indeed, the factors that [Robert] Feldman suggested that may lead to lower oil prices in the future are all unlikely to take place. So, expect higher and higher oil prices and, at some point, another ugly stagflationary outcome.

Nouriel has only ever been interested in one story: his perverse hankering for macroeconomic ruin for the United States.

posted on 11 October 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(12) Comments | Permalink

Jim Cramer notes that reports of the death of the US consumer are greatly (and frequently) exaggerated:

As a former obituary writer, I know that you must call the funeral parlor to make sure a person’s dead before you pronounce him so in the newspaper. So would it be too much to ask if economists, analysts and hedge-fund managers did the same before pronouncing the American consumer dead? In 25 years of trading stocks, I’ve read the consumer’s obituary more times than I care to imagine; each time the facts have proven the obit premature. For the last year, though, the negative-pundit nexus has unleashed a fusillade of consumer death notices…

It’s time for these permanently pessimistic pundits to accept the market’s judgment. If I’d ever written a premature obituary, I’d have been fired before the delivery boy could toss the papers from his bike. But these saturnine soothsayers just get to repronounce a new slaying on the next piece of data that hits the wires. Perhaps, at last, after these sparkling reports right on the heels of a year’s worth of death notices, we should at last recognize who’s worth listening to—and, especially, who’s worth ignoring.

Speaking of permanently pessimistic pundits, only Nouriel Roubini could attempt to put a bearish spin on the September non-farm payrolls release, which was better than expected in level terms and foreshadowed a massive 810k upward benchmark revision to the level of employment.

posted on 09 October 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

Nouriel Roubini attempts to argue that the benign experience of housing booms and subsequent downturns in rest of the Anglo-American world fails to invalidate his US recession calls based on a downturn in US housing.

First, Nouriel tries to argue that central banks in the UK, Australia and NZ have been more pro-active in targeting asset prices, in this case house prices, than the Fed. This is mere assertion on Nouriel’s part. The BoE, RBA and RBNZ have certainly referenced housing as one of many factors behind their recent tightening cycles, but all three central banks view their conduct of monetary policy as being squarely within the standard Taylor rule framework and are just as cautious as the Fed about the notion of central banks targeting asset prices. Indeed, if these central banks have been targeting house prices, they have done a lousy job of it. House price inflation in the rest of the Anglo-American world has if anything been even more pronounced than in the US and remains strong in NZ (this is ironic, because the RBNZ has actually given the strongest emphasis to housing in its official rhetoric). I highly recommend Adam Posen’s paper on the subject for a thorough debunking of Nouriel’s argument that monetary policy should target asset prices. Ben Bernanke also gave a speech on the subject before becoming Fed Chairman, in which he demonstrates how dangerous and misguided it would be for central banks to attempt to manage asset prices. To argue that the Fed is completely out of step with the rest of the world in its conduct of monetary policy simply beggars belief. If anything, the US under Volcker, Greenspan and Bernanke has set the standard that was subsequently emulated by other central banks by the adoption of formal inflation targets that sought to match the Fed’s record on inflation.

Second, Roubini argues that ‘What prevented a hard landing of the economy in the UK, Australia and New Zealand has been – among other factors – the fact that all three countries have experienced sharp positive terms of trade shocks that have boosted overall GDP at the time when the housing market was going into a sharp slump following the bursting of their housing bubbles.’ This statement somewhat contradicts his first argument that the soft-landings in these countries were a function of monetary policy. But it also ignores the fact that these terms of trade booms are not nearly as important to measured GDP growth as many people assume. The sectoral composition of the other Anglo-American economies is little different from that of the US, being overwhelming in services. Strength in commodity prices should not be confused with strength in commodity output, which is what real GDP measures. As we have noted previously, mining output in Australia fell 8.3% in the year to June. Net exports have made a flat or negative contribution to Australian GDP growth in every quarter since Q3 2001. As John Edwards likes to point out, Australian export volumes have even underperformed US export volumes. The increased national purchasing power due to a rising terms of trade has resulted in the substitution of imports for domestic production, which actually subtract from GDP, so terms of trade booms have mixed implications for measured GDP growth. Perhaps the best measure of the lack of importance of commodities for the overall Australian economy is the simple fact that some of the strongest GDP growth rates in the current Australian expansion were achieved during the 1998-2001 global commodity price slump.

Even Nouriel’s prolific colleague, Felix Salmon, is unconvinced by Nouriel’s arguments:

after looking at all the housing bubbles [sic] all over the world in the past decade, it’s hard to find a single one that has yet resulted in a hard landing. Nouriel seems to be saying that Australia, New Zealand, and the UK are all somehow special cases, but in fact, to me, they actually seem closer to the norm. Could the United States have a hard landing? Of course it could. But that would make it the exception, rather than the rule.

posted on 07 October 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

A Bloomberg story hints that the recent departure of Morgan Stanley Sinophile and ‘bubble’ drone Andy Xie may have had something to do with an internal email he wrote attacking Singapore as the host of the recent IMF and World Bank annual meetings. According to Bloomberg:

He questioned why Singapore was chosen to host the conference and said delegates “were competing with each other to praise Singapore as the success story of globalization.”

“Actually, Singapore’s success came mostly from being the money laundering center for corrupt Indonesian businessmen and government officials,” said Xie, who was based in Hong Kong before leaving Morgan Stanley on Sept. 29. “Indonesia has no money. So Singapore isn’t doing well.”…

“I tried to find out why Singapore was chosen to host the conference,” Xie wrote in the e-mail. “Nobody knew. Some said that probably no one else wanted it. Some guessed that Singapore did a good selling job. I thought it was a strange choice because Singapore was so far from any action or the hot topic of China and India. Mumbai or Shanghai would be a lot more appropriate.”

At a dinner party hosted by Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, “people fawned him like a prince,” Xie wrote. “These Western people didn’t know what they were talking about,” he wrote.

One could say the same about Andy.

posted on 06 October 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

‘Chairman’ Roubini, interviewed on CBS. As Brad Setser suggests, Nouriel is not quite as outrageous on television as he is on his blog, where he is describing the current rally in US equities to new all time highs on the Dow as a ‘delusional sucker’s rally.’ When analysts start describing markets as irrational, it’s usually a good indication that the market is in the process of invalidating their macro view.

Rather than assuming that millions of equity investors are delusional, James Hamilton attempts to reconcile the apparent divergence in equity and bond markets:

stock prices reflect both expectations of future profits as well as current interest rates. A lower real interest rate means that the present value of future earnings has increased even if the earnings themselves are no higher, because future flows are discounted less. Furthermore, the stock market has always exhibited an aversion to inflation as well. Hence, even if investors’ forecasts of future profits had not improved, one might still expect to see stocks appreciate as a direct result of a lower real interest rate and lower expected inflation. In other words, part of the stock market rally could be viewed as the logical companion of that for bonds. But the magnitude of the stock market surge seems too large to attribute to this alone, and certainly is grossly inconsistent with the assertion that investors believe the U.S. is about to enter a recession…

Current fed funds futures and option markets are betting that the fed funds rate will be down to 5% by next spring. And yet, in public statements the Fed seems to be communicating that, if it makes any changes, it is more likely to be toward higher rather than lower rates.

Well, here’s a story that I believe could reconcile everything. The housing slowdown is significant, real, and upon us now, but this is as bad as it’s going to get. Inflation numbers will begin to look better, allowing the Fed some breathing room to bring rates down slightly, averting a complete meltdown in housing. We get slower real economic growth, the biggest burden of which is borne by homebuilders. But the benefits of taming inflation bring some cheer to the rest of Wall Street and perhaps Main Street.

In other words, markets seem to believe that Bernanke is going to pull off the soft landing after all—slower real growth for sure, lower inflation, but no recession.

Fed Vice Chair Kohn envisages a similar scenario.

posted on 05 October 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(0) Comments | Permalink

While this blog likes to make fun of economists who perpetually forecast gloom and doom, at least most economists would generally concede that secular trend is up, whatever the cyclical ups and downs along the way.

By contrast, Kurt Andersen notes an apocalyptic zeitgeist that seems to unite ‘Christian millenarians, jihadists, Ivy League professors, and baby-boomers:’

Not so long ago, it was only right-wingers and old crackpots making decline-and-fall-of-Rome claims about America. But Niall Ferguson is a young superstar Harvard professor, and he argues that we—undisciplined, overstretched, unable to pay our bills or enforce our imperial claims, giving ourselves over to decadent spectacle (NASCAR, pornography), and overwhelmed by immigrants—do indeed look very ancient Roman. He suggests, in fact, that Gibbon’s definitive vision—the “most awful scene in the history of mankind”—is about to be topped.

Andersen suggests that this preoccupation with apocalyptic scenarios may partly come down to baby-boomer pathology:

It’s also a function of the baby-boomers’ becoming elderly. For half a century, they have dominated the culture, and now, as they enter the glide path to death, I think their generational solipsism unconsciously extrapolates approaching personal doom: When I go, everything goes with me, my end will be the end.

It should be said that economists are not entirely off the hook in terms of being excessively pessimistic, as this paper by Robert Fogel notes:

At the close of World War II, there were wide-ranging debates about the future of economic developments. Historical experience has since shown that these forecasts were uniformly too pessimistic. Expectations for the American economy focused on the likelihood of secular stagnation; this topic continued to be debated throughout the post-World War II expansion. Concerns raised during the late 1960s and early 1970s about rapid population growth smothering the potential for economic growth in less developed countries were contradicted when during the mid- and late-1970s, fertility rates in third world countries began to decline very rapidly. Predictions that food production would not be able to keep up with population growth have also been proven wrong, as between 1961 and 2000 calories per capita worldwide have increased by 24 percent, despite the doubling of the global population. The extraordinary economic growth in Southeast and East Asia had also been unforeseen by economists…

One of the points [Kuznets] made was that if you wanted to find accurate forecasts of the past, don’t look at what the economists said. The economists in 1850 wrote that the progress of the last decade had been so great that it could not possibly continue. And economists at the end of the nineteenth century wrote that the progress of the last half century has been so great that it could not possibly continue during the twentieth century. He said you would come closest to an accurate forecast if you read the writers of science fiction.

posted on 01 October 2006 by skirchner in Culture & Society, Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

David Miles and Melanie Baker discuss the differences between the US and UK housing markets, suggesting that only so much can be inferred from the UK experience for the US. While there are structural differences between the UK, Australian and NZ housing markets and their financing, I don’t think these differences make a compelling argument that the cyclical implications of housing weakness in the US will differ substantially from the generally benign experience of the rest of the Anglo-American world. Indeed, Miles and Baker share my view that the nexus between housing and consumption that Dr Strangelove (aka Nouriel Roubini) relies on for his US recession call is not as strong as conventionally assumed:

one should be sceptical on the strength of the link between housing markets and consumer spending. Although we agree that there is a degree of linkage (e.g., through changes in housing market activity driving purchases of certain types of household goods and through changes in the available collateral for household borrowing — home equity withdrawal is more than 5% of disposable income in both the US and the UK), this linkage is probably variable over time and may not even be especially strong.

Three points are significant: 1) just because house price movements and consumer spending movements may be correlated, this does not imply a causal relationship between them. An observed correlation may simply reflect movement in other factors which affect both house prices and consumer spending, e.g., interest rates, labour market fundamentals and income expectations; 2) Just because housing constitutes the largest part of household wealth (at around 54% in the UK once pension and life insurance assets are included), it does not follow that the value of housing has a very strong influence on consumer spending. Housing is not like other types of wealth. Most people live in the house that they own. If an owner is preparing to trade up, i.e., move to a bigger house (as many throughout the housing market are), then national house price rises do not make that household better off; 3). Those who trade down may gain from house price rises and those who trade up lose; these winners and losers should largely cancel each other out across the aggregate economy.

posted on 30 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

The missing link in the recession scenario of Dr Strangelove and others is the transmission mechanism from weakness in US housing to the broader economy. There are two candidates in this regard: the direct contribution to growth from dwelling investment; and the impact of house prices on household net worth and consumption.

In relation to the first channel, the growth subtraction from dwelling investment is unlikely in itself to tip the US into recession, even allowing for some spillover into other demand components. Most doomsday scenarios rely more heavily on the second channel. Estimates of the elasticity of consumption with respect to house prices vary, but again do not suggest that a downturn in house prices is in itself sufficient to trigger recession. This is especially the case when we consider the potentially offsetting contribution to household net worth from gains in equity markets and the high levels of direct and indirect ownership of equities by the US household sector.

As my associates at Action Economics note, consumer confidence is proving resilient to the recent downturn in the housing sector:

Today’s consumer confidence data from the Conference Board round out a unanimous mix of confidence measures showing increases in September. We expect these gains to carry into October, given that the litany of positive influences on the indexes from energy prices, stock prices, bond yields, and news headline effects seem to be approaching the new month with encouraging trajectories.

Though today’s reported confidence bounce was hardly a surprise, it adds to the evidence that housing sector weakness is at least thus far still contained to this narrow sector. If the drop in real estate market prospects is to have a psychological impact on consumer spending, then presumably it should similarly impact confidence. As we noted in our commentary last week, it is unlikely that we will see a direct “wealth effect” of the housing market correction as long as rising stock prices leave a solid trajectory for household net worth overall.

It is often said that a downturn in house prices will lead people to ‘stop consuming.’ This is partly just sloppy language, yet few people seem to give much thought to how implausible this really is. The consumption share of GDP is typically fairly stable, not least because a large component of consumption expenditure is non-discretionary. While changes in consumption can certainly make a large contribution to (or subtraction from) growth in a given quarter, consumption is typically the demand component about which we should be least worried.

posted on 27 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Former federal Labor minister Barry Cohen, on lunch with Mark Latham:

Latham also has memory lapses. He forgot to mention what happened during lunch. Having raised three sons, we should have known better than leave my wife Rae’s prized piece of porcelain on the coffee table. Oliver, a two-year-old, picked it up and smashed it into a thousand pieces - at his father’s feet. It was not Oliver’s fault, but ours.

Rae showed remarkable restraint. White knuckles, an intake of oxygen and a gurgled “Oh, dear”, was her only indication of pain.

Mark showed even greater restraint. He didn’t even notice. No apology. No “I’m sorry”. No attempt to clean up the debris. Nothing. It was a minor incident in life’s rich tapestry but it revealed the true nature of Mark Latham.

As he departed, the First Lady hissed through gritted teeth: “If that bastard ever becomes leader of the Labor Party, I’m voting Liberal.” She kept her promise. Fortunately for Australia, she was not alone.

posted on 26 September 2006 by skirchner in Politics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Terry McCrann (sadly, no link, but see the dead tree edition of the Weekend Australian) responds to Ross Gittins’ latest martyrdom operation:

There is nobody in the media or economic policy and tax circles in any doubt that Costello looks at [George] Megalogenis in the same way he would at a rabid dog which had literally bit into his belly.

And that sits in this paper’ broader sustained, coherent and consistent critique of Howard government policy - especially on tax, but more broadly. If any single paper has got under Costello’s skin - but in a substantive not a snide sniping, Fairfax, way - it is The Australian. Just think Freedom of Information…

Someone like Gittins is “authorized” to write column after column of bilious personal opinion: essentially, I hate Howard. Occasionally if unintentionally interrupted by some substantive argument or fact.

And if Howard - in truth, someone in his office - were to respond, up goes the cry, a la this last column: bully-boy, attack on free speech, and really inanely pompous sentences like this one: “One isn’t supposed to write about such behind-the-scenes bullying, of course.”…

Gittins claims that Howard’s “big lie” was his scare campaign over interest rates. Yet in the very same column he argues that budget surpluses are critical to low rates; and attacks the government for not having bigger surpluses - causing rates to be a “fraction higher than otherwise.”

McCrann is just getting warmed up. Go get the print edition for more.

posted on 23 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Felix Salmon points to an article by Barry Eichengreen, which argues that:

Only the continued buoyancy of prices in Perth, in the far west of the country, has prevented prices nationwide from falling more dramatically. All this offers a hint of what the US has in store.

Unfortunately for Felix, this blog has already dealt with this argument:

The upswing in global commodity prices that began in 2002 explains much of this regional variation, adding to incomes in the resource-rich states and driving the inter-state migration flows that the RBA has identified as an important source of weakness in Sydney house prices, which have now largely converged back to the same ratio to other capital cities seen in the early 1990s. While many people have argued that, but for the commodities boom, the rest of Australia would look like Sydney, it is more plausible to argue that Sydney is only as weak as it is because the commodities boom has drawn people away from Australia’s largest city.

Eichengreen also wants us to believe that only the commodity price boom saved the Australian economy from a housing-led downturn:

So why is the Australian economy holding up so well? The answer comes in two parts. First, strong commodity prices are a boon for Australia. The country is a big producer of aluminium, copper, nickel, coal and iron ore, all of which are in strong demand globally, and especially in neighbouring [sic] China. To Australians it seems as if there is no end to China’s demand for these commodities.

While the boom in commodity prices has certainly been important to the Australian economy, it hasn’t done as much for measured GDP growth as many analysts would like to think. Most people would be surprised to learn that mining output in Australia fell 8.3% in the year to June. Net exports have made a flat or negative contribution to Australian GDP growth in every quarter since Q3 2001 (a fact that should not have escaped an ersatz doomsday cultist like Felix!) As John Edwards likes to point out, Australian export volumes have even underperformed US export volumes. The increased national purchasing power due to a rising terms of trade has resulted in the substitution of imports for domestic production, which subtract from GDP. Where the commodity boom shows up is in growth in gross domestic income, which has held up significantly better than GDP growth. However, given the high level of foreign ownership of the Australian resources sector, this partly benefits foreign equity owners (see Australia’s net income deficit, much maligned by Nouriel). If Australia were anywhere near as reliant on commodities as many analysts seem to believe, then the Australian economy really would be in dire straits.

While many pundits are desperate to believe that the US is destined for housing-led economic ruin, there is little support for this proposition in the experience of the other Anglo-American economies that have been front-running the US housing cycle.

posted on 20 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink

News Ltd maintains its scrutiny of the Reserve Bank by way of FoI legislation:

GREAT to see the due process that goes into appointing the people who set our interest rates. While Glenn Stevens took over this week from Ian Macfarlane as governor of the Reserve Bank, an appointment properly trumpeted several weeks ago, there was no such announcement about the future of board member Warwick McKibbin, whose five-year term was to end on July 30. As business closed on Friday, July 28, there was still no official announcement about his future, which was a bit of a concern as board members are usually sent the board papers by secure courier the Friday* before a Tuesday meeting. So, with no official announcement, did the bank send McKibbin the papers for the meeting on August 1? A Freedom of Information request to the bank has revealed that they did, but only after a third “oral reassurance” from Treasury that McKibbin was staying in his job. RBA secretary David Emmanuel was told by Treasury on July 19 that the re-appointment had been cleared but Treasurer Peter Costello had yet to sign the letter. By Thursday, July 27, Treasury told the bank the Treasurer had signed off and the announcement would be made on Friday. It wasn’t, but Treasury still advised that it was all legal and would go ahead. McKibbin got his papers, the board met and increased interest rates. Phew.

* [actually Thursday, if memory serves - ed]

posted on 20 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Ross Gittins launches another one of his regular martyrdom operations:

except for people in privileged positions like mine, economists do have to be brave to stand up to the Howard Government with its behind-the-scenes bullying.

This is all a little bit precious, not least because it was a practice for which the former Labor Treasurer and Prime Minister, Paul Keating, was equally notorious, which is to say that none of this is anything new (and therefore hardly newsworthy). While there may be some economists at certain investment banks touting for government business who have to worry about such political pressure, that is a conflict of interest within the bank, not a problem with political pressure as such. If CEOs or their economists cave in to political pressure, it says more about them than it does about the government.

There was one occasion when I was working for Standard & Poor’s when I managed to get a phone call from the Prime Minister’s office, the Treasurer’s office and the office of the leader of the Opposition, all on the same day. Far from feeling any political pressure, I took considerable comfort from the fact that both sides of politics had been more or less equally annoyed. What was undoubtedly intended as political pressure was if anything useful feedback!

posted on 18 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics, Financial Markets

(5) Comments | Permalink

Since the Treasurer and incoming Governor of the Reserve Bank have largely recycled the previous Joint Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy to coincide with commencement of Glenn Stevens’ term as RBA Governor, it seems like a good occasion for me to recycle my previous criticisms of the governance arrangements for Australian monetary policy.

A curious feature of this and previous Joint Statements is the assertion that:

The Government and Bank continue to recognise that outcomes, and not the arrangements underpinning them, will ultimately measure the quality of the conduct of monetary policy.

At one level, this is an unexceptional statement: we do not want to privilege processes over outcomes. Yet by the same token, we are not indifferent to the way in which policy outcomes are achieved either. The fact that the government and RBA feel the need to say something about this betrays a certain defensiveness about the RBA’s governance arrangements, implicitly recognising that they are out of step with world’s best practice.

The RBA’s successful track record in the implementation of policy since the early 1990s effectively backs its claim that the ‘Nike’ or ‘just do it’ approach it shares with the Fed makes statutory reform of the RBA Act to put in place a more rigorous transparency and accountability regime unnecessary. There are also some supporting empirical studies, although isolating the effect of institutional arrangements on macro and financial market outcomes can be a fiendishly difficult exercise.

At the same time, the RBA has never gone so far as to say that a reformed governance framework would be detrimental to monetary policy outcomes (its actions with the government before the AAT in suppressing the release of information about the Board’s deliberations notwithstanding). What the government and RBA fail to recognise is that reform of the governance arrangements for the Bank may have procedural value that is independent of its implications for the actual conduct of monetary policy. Even if the actual policy outcomes were the same, the worst that could be said of a reformed governance framework is that these arrangements are superfluous. In fact, transparency and accountability are to be valued in their own right and not just for their implications for policy outcomes. Good policy outcomes are ultimately a poor justification for bad policy processes.

posted on 18 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(2) Comments | Permalink

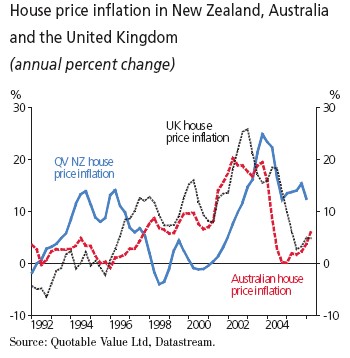

The forecasts of 20-30% declines in US house prices being offered by the usual suspects will be all too familiar to those in the rest of the Anglo-American world, which has been front-running the US housing cycle, and where such doom-mongering was also commonplace, at least until recently. Not so long ago, an article in the FT gave a run down of the long and disreputable history of doom-mongering in relation to UK housing. This week’s RBNZ Monetary Policy Statement produced the following chart, showing what has happened with UK, Australian and New Zealand house prices:

The experience of Australia and the UK is remarkably similar. The resilience of house prices in New Zealand reflects the sharp inversion of its yield curve, which has facilitated fixed rate lending below floating rates, so that the effective mortgage rate has not fully reflected the significant monetary tightening put in place by the RBNZ. Given the significant amount of NZ mortgage debt coming up for re-pricing over the next two years, the RBNZ is forecasting annual house price growth bottoming out at around -5% by the end of 2007, returning to flat growth by the end of 2008, but the RBNZ admits that housing has proven much more resilient than it expected.

posted on 15 September 2006 by skirchner in Economics

(0) Comments | Permalink

Page 80 of 111 pages ‹ First < 78 79 80 81 82 > Last ›

|